With Israeli jets flying over Lebanon, I was convinced that teaching Jewish philosophy in Beirut would be a tough sell. But as my Sunni, Shia, Christian, and Druze students at the American University of Beirut began reading and discussing Maimonides this spring, I was pleasantly surprised.

Though Lebanon officially recognizes 18 different religious confessions (including Judaism), teaching a course on Judaism, Christianity, and Islam was no easy feat--especially with car bombs detonating almost every week. When the blast of a twin suicide bombing ripped through the home of one of my students, I urged her to leave class to be with her family. "I would rather stay here," she said, showing me photos of her living room in ruins on her phone. For many students, the classroom is a sanctuary, and the free exchange of ideas across "enemy" lines is a communion unlike any other.

Our philosophical odyssey began with St. Augustine's Confessions. Reading Augustine in Beirut, the party capital of the Middle East (where trauma is treated with booze, and plastic surgery bandages are worn with pride), my students were particularly intrigued by Augustine's conviction that his addiction to the temptations of the material world caused his unhappiness and "madness." In a country where rigid allegiance to religious identity triggers gunshots and political deadlock, Augustine's theory that memory is the mechanism through which we construct and maintain a distinct sense of "self" struck my students as an enticing proposition.

Like Augustine, we contemplated the fragility and power of our own personal narratives, and wondered: "What is my nature?" His answer: "A life that is ever varying, full of change, and of immense power."

Moving on to Islamic philosophy, we turned to the "Deliverance of Error" by al-Ghazali, a 12th century Sufi whose criticism of inherited belief and blind faith in religious authority made several students who were skeptical of Sufism reluctant to read him. Though al-Ghazali was the top Islamic scholar of his day, a spiritual crisis compelled him to give up his prestigious teaching post, and step onto the Sufi path of self-transcendence. After relinquishing his reputation and wealth, al-Ghazali embarked on a spiritual retreat to Damascus and Jerusalem to make a "moral change," and purify his heart. "To the mystics," he noted, "all movement and all rest, whether external or internal, brings illumination."

Reading about al-Ghazali's mystical transformation from a master of Islamic law to a master of the human heart inspired the same students who were raised with negative stereotypes about Sufism to pursue a more sincere and dynamic faith of their own--fueled by passion and inquiry, instead of dogma and imitation.

Since none of my students had ever read a Jewish text, they didn't know what to expect when we began reading Maimonides' medieval masterpiece, "A Guide for the Perplexed." The Muslim students were just as surprised to learn that this revered Jewish philosopher from Cordoba had served as the physician of Sultan Saladin, as the Christian students were to learn that he had influenced the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas. As for me, I was surprised to see my students put their feelings about Israel aside to dive with fresh eyes into Maimonides' theology.

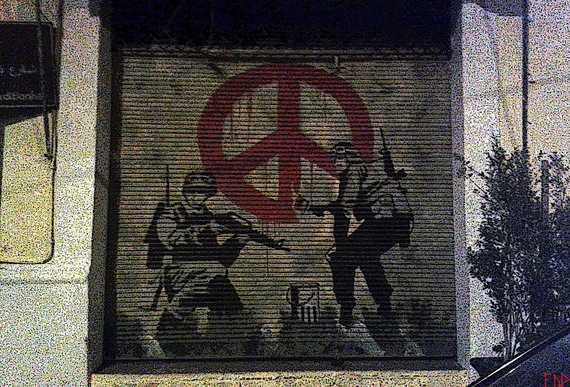

According to Maimonides, no words can describe the divine, since the human mind cannot comprehend or communicate a "great many of the properties of sensible things" and the "intelligible characteristics of that most excellent substance." Living in Lebanon, where militias regularly take up arms over who's right and who's wrong, my students could appreciate Maimonides' refreshing take on the limits of our "knowing" the natural world--and any hints of the divine. Instead of heeding some kumbaya call for religious tolerance, or dwelling on the theological overlap of the Abrahamic traditions, we found common ground in glancing with awe and humility at our profound inability to make sense of this bewildering world and our place within it.

Embracing our fallibility, we were able to marvel at the miracle and mystery of our own minds, recognizing the wise advice of Maimonides: "It is therefore more becoming to be silent, and to be content with intellectual reflection, as has been recommended by men of the highest culture, in the words 'Commune with your own heart upon your bed, and be still'" (Ps. iv. 4).

While rockets from Syria struck the north and suicide bombers blew themselves up in Beirut, my students shielded me from pessimism, by showing me that no amount of violence or division can keep open minds and hearts of vision from forging new points of connection--like the Druze student who invited us to a shrine dedicated to the Prophet Job, the Christian student who pointed out the parallels between al-Ghazali and the poet Khalil Gibran, and the Muslim student who can't wait to give Sufism a whirl. Their openness has inspired me to consider taking a field trip this fall to the Magen Avraham Synagogue in Beirut--whose damage from Israeli shelling was recently repaired with funds from Lebanese Christians, Muslims, and Jews at home and abroad.

Reading Maimonides in Beirut reminded me that beyond right and wrong, reason and faith, belief and unbelief, we are perhaps most alive and wise when we strive to become conscious of the "self." In the words of Maimonides, "For in every being that is conscious of itself, life and wisdom are the same thing, that is to say, if by wisdom we understand the consciousness of self."