A passion for jade has been an enduring hallmark of Chinese civilization for millennia. A rare, semi-precious hardstone, jade is made up of interlocking mineral fibers that make it notoriously difficult to work. Like the interwoven mineral strands of jade itself, the history of jade and jade collecting create an intricate story in which American collectors and museums are inextricably linked with ancient Chinese jades.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Amazon.com

Underlining that relationship is The Jade Age: Early Chinese Jades in American Museums a dual language publication by the American sinologist, Elizabeth Childs-Johnson, and the Chinese archaeologist, Gu Fung. Their unique bilingual publication intertwines the strands of jade history and collecting by presenting the contrasting history of jades in Chinese and American collections. Prominent among their themes is the differentiation between jade as art in American museums versus jade as artifact in Chinese collections.

Jade Art in American Museums

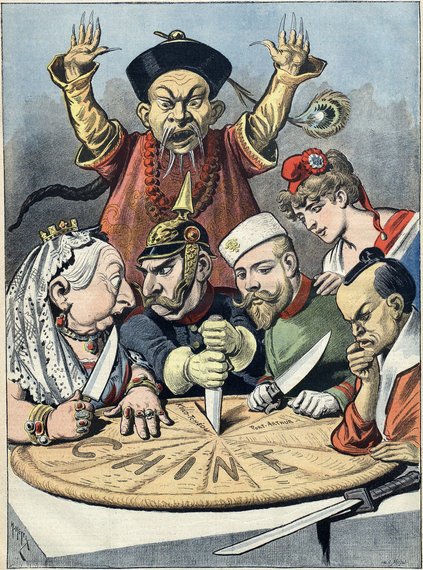

Ancient Chinese jades in American museums were primarily acquired as beautiful art. The majority of these jades were collected in China during what the Chinese call the Hundred Years Humiliation, 1839-1949. This was a time when China faced foreign invasions from powers intent on extracting its wealth. These foreign incursions were paired with domestic turmoil.

In a land besieged by foreign powers and plagued by internal unrest, there was no protection for China's cultural heritage. Beginning with the first Opium War of 1840 collections of Chinese art were up for grabs by foreign collectors.

This period of collecting, so poignant for Chinese, is considered the Golden Age of jade collecting by western collectors. In the United States, robber baron wealth of the Gilded Age stretched out its arms to embrace collections made available by both desperate Chinese owners and unscrupulous tomb robbers. Many great masterpieces of Chinese art found their way to the United States during these years.

Picture Credit: Henri Meyer for Let Petit Journal, 16 January, 1868, Bibliothèque national de Paris

Recognized and valued as rare and beautiful objects, ancient jades entered American collections as stolen, looted or bought acquisitions, stripped of their cultural context. American collectors were fascinated by ancient jades, but unable to connect them with early Chinese civilizations. Western publications of the early twentieth century claimed that China had no prehistory, no Neolithic nor age in which stone tools were made. The origins of China, it was claimed, were not Chinese. The rise of Chinese civilization was credited as an import from civilization to the west.

At the Field Museum of Chicago, the German-born anthropologist Berthold Laufer, was the last word on things "Oriental." Laufer claimed that archaeological and literary records showed "the Chinese have never passed through an epoch which for other culture-regions has been designated as a stone age."

At the same time, Laufer and other American collectors, had an insatiable love for jade. America's hunger for Asian antiquities led to a collecting spree as art collecting expeditions to China were financed by American museums. The Chinese side of this thirst for ancient jade was divided between scholars who wished to protect their country's historical treasures, and antiquities dealers who were intent on profits.

By 1912, Laufer was the leading Western expert on jade. During his tenure at the Field Museum, he made Chicago the center of American collecting of Chinese jade. His work as advisor and "authenticator" of Chinese art resulted in 450 publications and the acquisition of major collections of ancient jades in New York's American Museum of Natural History, Chicago's Field Museum and its Art Institute. Laufer (seated right) is pictured here during one of his collecting expedition to China.

Photo Credit: © The Field Museum, A98299

Early Jade Artifacts as Evidence for the Rise of Chinese Civilization

The publication of The Jade Age: Early Chinese Jades in American Museums by Science Press, Beijing, underlines the scientific value placed on jades by the Chinese. Jades in China are valued not just for their intrinsic beauty, but for their ability to shed light on the rise of Chinese civilization. Early jades excavated by Chinese archaeologists have entered China's national collections as artifacts as opposed to art.

Today, it is readily acknowledged that the origins of Chinese culture are (surprise!) Chinese. Furthermore, jade is seen as the cornerstone for the formation of Chinese civilization and the rise of early city-states throughout a broad region of China. Childs-Johnson, the leading American authority on ancient Chinese jade, proposes that the term "Stone Age," applied to ancient civilizations, be replaced by the term "Jade Age" in reference to ancient China.

Presenting jade as both art and artifact in the book, Childs-Johnson and Gu document jades manufactured during the Neolithic period through the early Xia, c. 3,500 BCE-2,000 BCE. They offer a study 430 pages long, including 200 splendid color plates, as well as maps, archaeological drawings and photos.

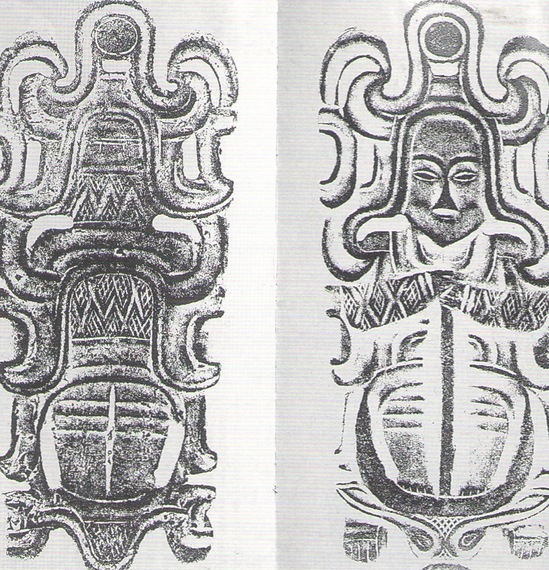

Over 1,500 years of the evolution of jade-working techniques, motifs and meaning are discussed using jades from three Neolithic jade-working civilizations: Hongshan, Liangzhu and Longshan. The complexity and variety of jade and jade-working during this time, is traced from stone prototypes to the emergence of standardized forms in the jade repertoire.

Evolution of Early Jade, c. 3,500 BCE-2,000 BCE

Chinese classics ascribe the rise of Chinese civilization to culture heroes who brought agriculture, water control and writing to mankind. Determined to replace ancient myth with modern science, the first generation of Western-trained archaeologists returned to China in the 1920s just as engineers, geologists and railroad building uncovered key early sites. China's new archaeologists used these sites to document the rise of Chinese civilization on Chinese soil, claiming their history for themselves and refuting long-held western beliefs.

Roughly a half century later, China's spurt of economic expansion during the 1980s uncovered further early archaeological sites revealing the rise of Chinese civilization. The controlled excavation of these sites made scientific dating of jades possible. Earlier collected jades could now be dated with accuracy. Further, the changing role of jade over the course of the Neolithic could be accurately linked with the rise of Chinese civilization.

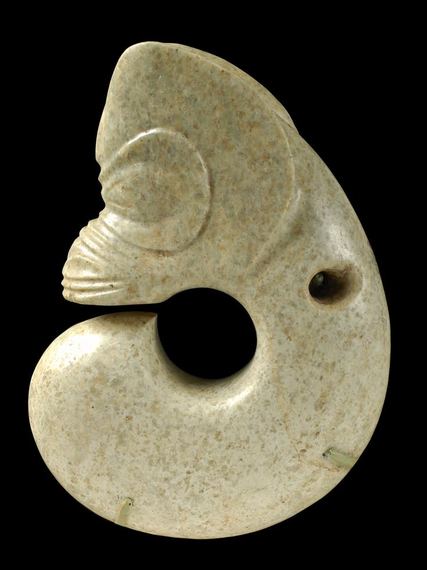

For the early Chinese of Hongshan (c. 4,500-3,000 BCE, situated in northeast China), jade had inherent supernatural properties. The earliest jade objects were tools for shaman wizards that they used to perform magic. Jade, including the so-called pig dragon motif, acted as a medium of communications with the gods and ancestors, protecting Hongshan from depredations and natural disaster.

The Hongshan elite were distinguished by the jade headpieces they wore. Elite Hongshan burials suggest that these hoof-shaped articles were held on the head with straps that tied under the chin, thus making the wearer taller in height and signalling higher status as well.

A Hongshan jade pendant displays a ruler or mythical figure wearing this elite head ornament.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Palace Museum, Beijing

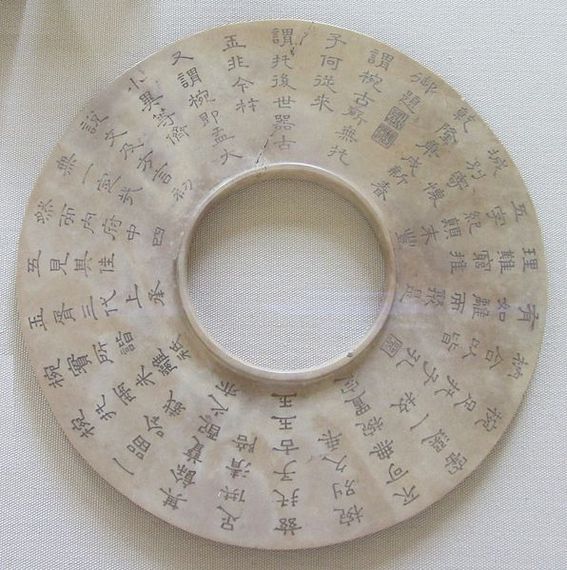

Over time, jades began to shed their role as a magical medium. Increasingly, jades began to take on the role of indicators of social status. Liangzhu culture (c. 3,000-2,000 BCE situated in the Yangzi River Delta) saw the emergence of the bi disk and cong tube in the Neolithic jade taxonomy. Burials of the Liangzhu elite contains jade objects almost exclusively, and often in great numbers. These objects, often intricately worked, represent a considerable amount of wealth and energy of Liangzhu society. Jade, ranging from 6.0 to 7.0 on Mohs Scale, was worked with a simple bow drill using chips of quartz or jade to cut and abrade the jade. Decoration was achieved by abrading the surrounding surface in a deductive method. The control of resources dedicated to these objects, show the rise of the ruling elite early Chinese city-state.

By the end of the Neolithic age, Longshan jade-working culture (c. 3,000-2,000 BCE, situated in the middle and lower Yellow River Valley), is marked by scepters in the shape of ancient stone tools. Intricately-notched rings found near the heads of Longshan elite in burials indicate that these rings served as hair rings, distinguishing the elite. The magical powers of jade have been replaced by social force of the stone.

By presenting jade as both art and artifact in a dual language text, authors Childs-Johnson and Gu provide readers in China and abroad with a full appreciation of jade. They discuss jade as finely-crafted object as well as providing an understanding of its role as a catalyst in China's early social and cultural development. The distinction is crucial to today's rising China, which proudly traces its roots back 5,000 years to jade-working settlements.

Spencer Throckmorton of Throckmorton Fine Art in New York City is the rare specialist offering ancient Chinese jade in his galleries. Asked about an appreciation for ancient jade today, he pointed to the Christie's auction of the collection of Robert Hatfield Ellsworth in March 2015. Throckmorton observed of the auction: "Every piece in the Ellsworth auction sold for significantly more than the estimate."

Photo Credit: Courtesy Christie's Images Ltd. 2015

When asked for a contemporary Chinese collector of Neolithic Chinese jade, Throckmorton pointed to artist activist Ai Weiwei, a figure also known for his embellishment of Neolithic vases with an American soft drink logo. Asked if there might be a problem including Ai Weiwei as an example of a collector appreciative of ancient jade, Throckmorton saw none. He pointed to the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735-1796), who collected ancient Chinese jade and had it engraved with his own poetry.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Stockamp Tsai Collection

Throckmorton Fine Art sponsored the photography in Childs-Johnson and Gu's book on ancient jade, citing the importance of a visual record as well as cooperation between an American and Chinese scholar. Their cooperation, as well as the respect they accord to one another, successfully binds together the many strands in the history of early Chinese jades in American collections, imitating the structure of jade itself. Perhaps the 21st century will be hailed as the true Golden Age of Chinese jade collecting, as it brings together scholars from China and America, helps forge a new era of cooperation and respect and establishes an appreciation of jade as both art and artifact.