I readily admit I do not have the capacity to translate any of my books into Spanish. Though I am proud of my heritage, I stopped speaking both Spanish and English for a full year beginning at age three. My parents were in a panic and took me to be "tested." The doctor (who was not Latino) gave my parents his prognosis: I was of normal intelligence (thank God!) but he told my parents to cut all Spanish from the house. My parents complied. I do not blame them: this was 1963 and the benefits of bilingualism were not understood in this country. Ever since then, I've struggled (in great embarrassment) with the language.

Now that I am a writer, I am awestruck by those who possess the facility to translate works of literature. How do they do it? Is the translation a new, separate work of art?

I recently had the opportunity to ask a practitioner a few questions about translation with regard to a book of poems originally published in Portuguese.

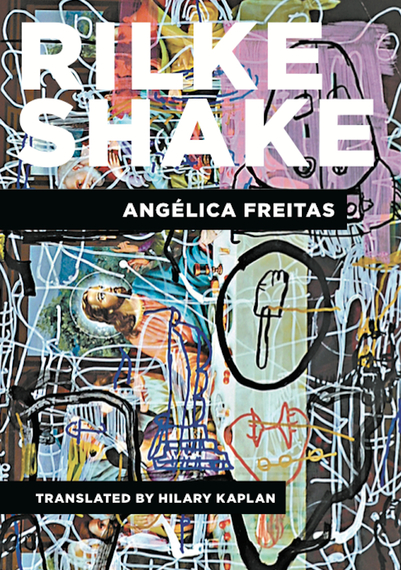

Hilary Kaplan's translations of Brazilian fiction and poetry have been featured on BBC Radio 4, in Modern Poetry in Translation, and in Granta. She is the translator of Rilke Shake (Phoneme Media) by Angélica Freitas, a nominee for the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, and Ghosts (Story Front), a collection of stories by Paloma Vidal. Her translations from Angélica Freitas's second books of poems, um utero é do tamanho de um punho ("the uterus is the size of a fist"), are forthcoming in Centres of Cataclysm.

You say in your Translator's Note that you first encountered Rilke Shake "while browsing the poetry section at Livraria Cultura, a large bookstore in Porto Alegre." What was it about Angélica Freitas's writing that convinced you to bring her work to the English-speaking world?

KAPLAN: The title grabbed my attention because it was funny! I had to see what was happening in this book that was shaking up Rilke--what could that mean?--and punning. ("Rilke shake" rhymes with "milkshake" in Portuguese.) How many times does a book of poetry make you laugh from the get-go? There might be a more humorous trend in contemporary U.S. poetry now, but in 2007, this title made me laugh when nothing else on the shelf in the U.S. or Brazil did. At the same time, in its questioning of identity and exploration of language and wordplay, the book resonated with a lot of contemporary U.S. poetry I was reading at the time. I recognized this voice, I could relate to it, but it was also going out there with humor and images in a way I hadn't seen before (for example, in the bathtub with Gertrude Stein), and that was exciting.

The playful sense of humor that's in the title is a current throughout the book. These are serious poems, about identity formation and finding one's place in the world, which involves love, politics, history, and fantasy. But they are grounded in concrete, everyday scenes, like opening a door or listening to music, and they use wordplay, humor, and vibrant imagination to explore their themes.

I was interested in the voice in the poems, because it was a voice I hadn't heard in Brazilian poetry before: funny, female, and speaking in the Portuguese of the south of Brazil, and in Spanish and English and other languages, too. The multivocality of the poems and their dialogue with Spanish Latin American poetry, and U.S. and European and Japanese poetry, stood out to me. It was also a queer voice, and that seemed unique among Brazilian poets--particularly when it comes to women writers--and worthy of attention.

Though translating prose seems like a difficult process on many levels, translating poetry--while keeping intact the "poetic voice" of the author--seems close to impossible. Could you talk a little about your process of translating Rilke Shake?

KAPLAN: I had fun. When you live with a book for so long, you also go through stages of pulling your hair out, but I always returned to the pleasure of this book. There's a joy in the poems that was infectious to translate and that I hope comes through for the reader. The element of play in the poems guided my translation. I played around with various possibilities for many of the poems, and then it was the process of settling into one and deciding. Or, shaking it up by the book's own imperative. I wrote seven versions of "the witches of brussels," a limerick. We only put one in the book, but [Founding Editor of Phoneme Media] David Shook and I made a chapbook of all seven. There are many possibilities when you're translating poetry.

When translating one's contemporaries, there is also the pleasure and possibility of talking with them. I reached out to Angélica after I'd translated some poems from Rilke Shake--she wrote me back from a bus in Romania! She is a gracious and open writer, and a translator herself, so we developed a generous dialogue. It was very moving to read with her last year--to hear her read her poems in her voice, live, and to read my translations alongside her.

Do you have a favorite poem in Rilke Shake?

KAPLAN: I love the poem that begins, "how lovely it would be to have a little mustache." It's a gender-bending take on "the man behind the mustache" in Carlos Drummond de Andrade's classic "Poema de sete faces" ("Seven-sided Poem"). Angélica's poem is premised on a question: What would it be like to be the man behind the mustache, to embody that mysterious character? The speaker imagines inhabiting the satisfying sphere of anonymity that the mustache, and male privilege, provide. There's a whole question of being, how to be, and different ways of being. It's a poem about transformation and desire.