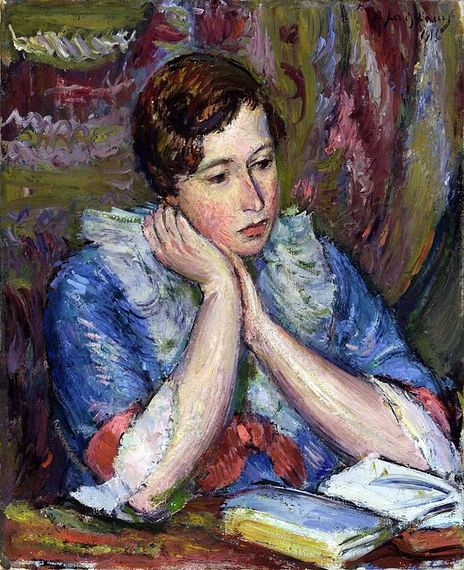

When your work requires research, there's no such thing as taking time off. Even if it looks like it. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons. Painting by Anton Faistauer.

Not all college professors spend their summer months running for Congress.

But nearly every college instructor I know fields some variation of this question: "So, do you actually work in the summer?"

My own mother asks it of me. My sister -- a teacher -- asked it last week.

Come on, now.

Binge-watching Netflix's latest offerings and reviewing the most popular Moleskine notebooks on Amazon involves work.

Yet, how we professors bristle at the insinuation that we don't have pressing things to do, that, because we don't (always) teach in the summer -- or at least not a full course load -- we aren't engaged in work. That if our work isn't visible, i.e., teaching in a classroom, then our work doesn't exist and can't be understand as work.

What many of us professorial types do do during the summer months, as a break from scrolling through the cultural richness of LOL Cats, is research. But this research endeavor is messy. It's filled with jolting starts, stops and roadblocks (intellectual and material), and it's hard to do and harder to describe.

So sometimes I head to the grocery store in the middle of the day to clear my head. Therefore, when you see me in the frozen foods section at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday, perusing the bagged artichokes for $3.79 and the pearl onion medley on special, it's not because I have nothing else to do.

It's because I'm an excellent procrastinator.

But an excellent procrastinator at what, you might ask.

So we've circled back to research.

I have a hard time telling people in the summer that I "do research." That answer sounds cryptic. It sounds condescending. Also, I don't want to encourage any follow-up questions (regardless of how sensible they may be) when running into an acquaintance in the frozen foods aisle. As in:

You do research on ... ?

It provokes anxiety -- especially when it interrupts my pondering frozen artichokes: Can they be sautéed? Or is a boring boil a safer bet?

If you were to observe me engaged in research, you'd see a woman reclining in her La-Z-Boy, books perched on the armrest and computer in lap. It doesn't look too laborious. But my mind is like a pinball, racing from one point to another before losing track of my third point on the intersection of gender, power, political elites and interview methodology. My mind -- now vacant -- pursues the dead-ended version of a researcher's self-loathing: Why is it so hard to think about things? To produce knowledge? To offer evidence? To test theories and connect all of this to previously published work in the field?

I'd much rather peruse the selection of artisanal cheeses at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday.

I calm myself by remembering the Socrates quote: "The unexamined life is not worth living." I'm examining something, therefore I have purpose. The cognitive fuzziness begins to retreat for the moment.

Lately, in an attempt to divert detours into research conversations, I've answered the "summer work" question this way:

"I write journal articles."

You write articles in your journal?

Well, it's not all that different in terms of the number of readers.

So what keeps me going during these summer months, you perhaps wonder?

It's my attempt to create knowledge, a dangerous and cutthroat endeavor because knowledge, we're told, is intricately linked to power. Sociologist Albert Hunter writes in the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography that "Differences in the distribution of knowledge are a source of power, and power may be used to generate and maintain differences in the distribution of knowledge. Knowledge, then, is a scarce resource."

In other words, "research" may look like I'm zoning out, sprawled on my Laz-Y-Boy with the footrest fully extended. But in my head, it's pretty much academic "Game of Thrones" all the time.

Until I head back to the grocery store. See you in aisle 12 around 11 a.m., anyone?

This post originally appeared on Cognoscenti, the commentary site for WBUR Boston.