The G-20 Summit is in Pittsburgh later this week. Leaders from the 20 countries that collectively represent two-thirds of the world's population, 80 percent of world trade and 90 percent of global gross national product, will meet to discuss the global economy and terms of trade.

It is fitting that they meet in Pittsburgh. Steel City is renowned for the slump in its dominant industry, followed by what President Obama called a "world-class" transition to a diversified economy, including higher education, bio-tech and clean energy. The good news is true enough -- credit where due -- but the praise misses half the story.

Yes, some manufacturing jobs in Pittsburgh were replaced by high-end jobs in education or medicine. But many were replaced by jobs in hotels and food services -- jobs that never paid as well and proved even more vulnerable in the recent downturn. Some manufacturing jobs were never replaced at all. That helps explain why the city's population is declining, especially among youth, who seek opportunity elsewhere.

Two lessons from Pittsburgh are important for the United States and the G-20 Summit. We discuss them in our new report, Pittsburgh, G-20, and the New Economy -- Lessons to Learn, Choices to Make.

The first lesson is the importance of the real economy. America grew up as an industrial superpower, from mass-produced automobiles to the Arsenal of Democracy. But our once-robust system of economic production -- the invention, design and manufacture of products -- has been steadily eroded. In its place has come an economy based on asset bubbles and foreign borrowing. That economy was never sustainable and is no longer available.

We need to dispel the notion that America has moved beyond the production of goods. From cars to computers to refrigerators, a country needs things. If we don't make those things here, then someone else gets our money.

Too many modern Americans associate manufacturing with horse carts and buggy whips. We think of dirty old industries that economic evolution will naturally replace with high-end services in America and low-wage workers in other countries. We don't appreciate that manufacturing still constitutes 12 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, 60 percent of U.S. exports and 70 percent of private sector research and development. If we hope to move beyond the production of goods, we need to think what would replace it.

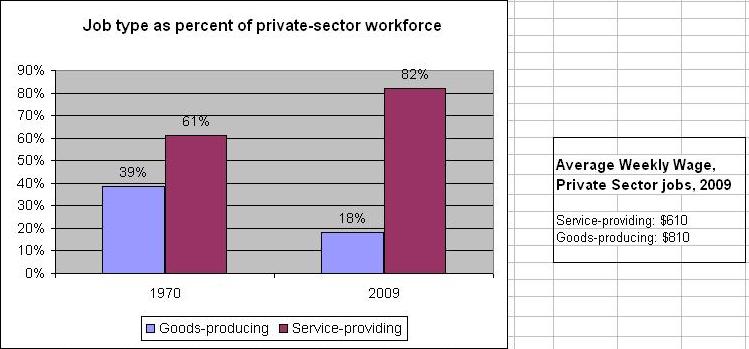

We tried over the past thirty years to replace goods-producing jobs (down 54 percent) with service-providing jobs (up 34 percent). It hasn't worked so well. First, because our deficit in goods far exceeds our surplus in services -- $840 billion versus $160 billion-- so our accounts are out of balance. Second, service jobs don't pay as well. Even in the broad category of "services" -- which includes high-end professionals like doctors, lawyers and investment brokers -- service-providing jobs have an average weekly wage of $610 compared with $810 in the goods-producing sector. Service jobs pay 75 cents for every dollar paid a production job. Retail jobs pay 50 cents.

Source: BEA and Campaign for America's Future.

This change helps explain the "lost decade" in the latest Census Bureau data. Median household income dropped a thousand dollars in the ten years before 2008, the only ten year period in census records in which incomes failed to rise. It's easy to predict that 2009 will be even worse.

The second lesson from Pittsburgh is the connection between the production of goods and their sale. Trade, that is.

Many countries find it appropriate to enact protectionist and mercantilist polices to their individual advantage. The U.S. generally does not, however, citing its ideological commitment to free trade.

As a result, steel manufactured in Pittsburgh is competing against steel manufactured in China with devalued currency, government subsidies, deeply suppressed labor rights, and lower (cheaper) environmental and safety standards. Many products imported into America violate safety standards that U.S. manufacturers are required to obey, like lead-based paint in toys and pesticides in foods. American producers bear the cost of higher standards for the benefit of American citizens. Other countries avoid these costs with minimal consequences in the U.S. market.

The G-20 Summit in Pittsburgh provides an opportunity for Americans to look at what's happening, and ask hard questions. It provides opportunity to move beyond shibboleths of free trade and protectionism, and to question the true functioning of the market. Obama's decision to apply tariffs to remedy the "market disruption" of tires from China is a first step in this new direction.

The Summit also provides an opportunity to examine American patterns of production and consumption. Even when the economy was growing, America ran a current account deficit in excess of $700 billion every year. We borrowed $2 billion every day to cover the difference. That might have worked well for the countries we bought and borrowed from -- but it worked less well for America. It was never sustainable, anyway.

As the G-20 leaders plan a recovery from the global downturn, they should not assume that the United States will remain the world's consumer -- spending more than we earn, and paying for it with personal and national debt. The G-20 must chart the process by which the global economy that emerges from the crisis is more balanced, and less dependent on U.S. consumption. Growth must be sustainable in Pittsburgh as well as Beijing.

-------

This piece originally appeared at the Campaign for America's Future.