When I meet Kevin* inside a Tijuana shelter, he stares straight into my eyes and asks me an urgent question. Can you pass me over there? He's slender, 16, and the words fall from his mouth without pause. He's been here along the border for a few days now, 1,800 miles from the jagged hills and rural countryside of his native Guerrero, Mexico. Kevin likes Tijuana, thinks it's grande, libre, una ciudad bella. But he's still desperate to leave. The problem is, like many unaccompanied youth, he doesn't have an exact destination, or a plan. Kevin's godfather, who raised him, is already somewhere in the U.S. "Allá están a la luz del mundo, a la luz del día," Kevin says. At home, organized crime operates in broad daylight, for everyone to see, he tells me. After his godfather received death threats and fled, Kevin says he was also threatened. He tried moving to another neighborhood, but it was only a matter of time before the wrong people happened to glimpse him again. So now, Kevin is headed north. He knows his godfather is in the States. He just doesn't know where.

A Steady Flow North

Over the past month, the plight of migrant Central American children and teens has alternately captivated, saddened and enraged swaths of the American public. But children and teens from Mexico, who travel north for similar if not identical reasons, have been largely absent from the conversation.

"To me they're the same," says Dr. Alejandra Castañeda, an investigator at the Mexican think tank El Colegio de la Frontera Norte and author of the book The Politics of Citizenship of Mexican Migrants. "I don't see a lot of differences, if you look at it in terms of the region."

Migration in general from Mexico has plummeted over the past few years, balancing out at net zero, but Mexican minors maintain a steady flow northward.

Apprehensions for Mexican kids traveling without a parent or guardian reached an all-time high last year in 2013, when U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported snagging 17,240. That's an average of 47 per day, or 42 percent of the total unaccompanied child population. In comparison, the agency apprehended 8,068 Guatemalan kids, 6,747 Hondurans, and 5,990 Salvadorans in 2013.

"There's always been volume from Mexico coming to the U.S.," says Mark Hugo Lopez, director of Hispanic research at the Pew Research Center. "The Mexican numbers back to 2009 has been 11 to 12,000 kids arriving illegally in the U.S. each year."

The rate has remained steady. For fiscal year 2014, a total of 12,146 Mexican kids have been caught along the border. That's 25 percent of the unaccompanied child population snagged this year, the second largest number of kids behind Honduras.

The majority of Central American and Mexican children flee their home countries for the same reasons, says Elizabeth G. Kennedy, a Fulbright researcher working with kid migrants in El Salvador as part of a doctoral dissertation on unaccompanied youth.

"They are afraid of forced gang or cartel recruitment and high levels of crime and violence targeted at young people," Kennedy says. "At the same time, many live in extreme poverty and hope to obtain a better life for themselves and their loved ones through study and hard work."

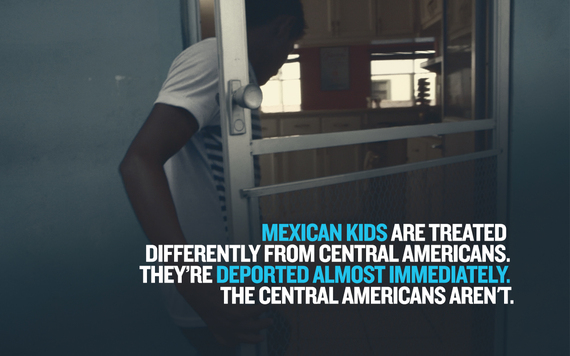

But there's a big difference between how Mexican and Central American kids are treated once they cross the border. Mexican children and teens are deported almost immediately, in what's called expedited repatriation. The Central Americans aren't-- that is, yet.

The vast majority of Mexican teens and children picked up by the Border Patrol never set foot in immigration court, which saves the U.S. money while severely limiting their chances of applying for and obtaining legal relief.

Some politicians are now discussing plans for legislation aimed at removing Central Americans kids in a similarly expedited fashion.

Right now, the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), implemented in December 2008, defines how kids are processed. The law, which President Obama reportedly wants to change, was designed to protect youth victimized by human traffickers and gangs. It mandated children arriving from "non contiguous countries" were immune from immediate deportation. Instead, they're now transferred into the custody of the Office of Refugees and Resettlement, and given a future court date to make a case for staying in the U.S., through an asylum claim or by obtaining a Special Immigrant Juvenile Status visa.

But since Mexico and Canada are considered "contiguous" neighboring countries under the TVPRA, their citizens don't get a day in court, and the large majority never have contact with the Office of Refugees and Resettlement.

Although the TVPRA enactment was, in part, due to "ongoing concerns" that children apprehended by the Border Patrol "weren't being adequately screened to see if there were a reason that they should not be returned to their home country," according to a recent Congressional Research Service report, the Border Patrol still calls the shots for Mexican kids. Individual agents decide what to do with each encountered child, and most kids are quickly and quietly removed.

"The way that the Mexican children are treated is unjust," says Bryan Johnson, a Long Island immigration lawyer who currently represents around 100 unaccompanied migrant youth from Central America. "It's kind of ignored, I think... The kids are here for less than 48 hours, and then dropped on other side border. They're an invisible population."

Two Distinct Processes: The Mexican Difference

The process of removing Mexican minors is streamlined, simple and undeniably cheaper for the United States. The Border Patrol picks up a kid. He or she is brought to a Border Patrol station, where they're then questioned inside a secondary screening office, temporarily detained according to specific kid-friendly rules, and given free snacks and juice.

If they're confirmed to be traveling alone, without documentation, then the consulate of their home country is supposed to be notified immediately. Simultaneously, an invisible stopwatch starts ticking. The Border Patrol has a maximum of 72 hours in which to transfer kids to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) -- a process that also involves a third government agency, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, responsible for the actual physical transport of the young detainees. For Mexican kids, the process is abbreviated. Border agents have just 48 hours to repatriate them to their country of origin.

That means they rarely end up the government-contracted network of temporary shelters, like most Central American kids. Honduran, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan migrant children and teens can stay in protective custody for months, and in some cases years, until their court hearing determines whether or not they're eligible for relief...