I've complained numerous times in this space about the endless claims from media pundits that "TV is dying." Despite pronouncements by experts like David Carr and miscounted viewership by Nielsen, I can assure you, TV IS NOT DYING. That said, despite a current heyday of creativity and originality -- Television does have something wrong with it.

Yes, as Carr pointed out and Nielsen reported, "traditional TV viewing" has eroded. However, it has not been replaced by something other than TV, it's been replaced by more TV, just on other platforms. In some cases, those other platforms are legal; in other cases they are not. As Brian Stelter demonstrated last week, many twenty-somethings are using their parents' HBO GO account to watch Girls, without a TV. As TorrentFreak points out, many others are simply stealing TV.

I've said it before and I'll say it again: TV is not a device -- it is an experience. Prime Time is not a time slot -- it is an expectation of story-telling quality. 'Television' is an emotional exchange between artists and their audiences, regardless of where, when and how it takes place. No matter how these digital whippersnappers are doing it, by hook or by crook, they are still watching that stuff we call TV.

But, despite my staunch defense of the health of TV, the economic ecosystem of the TV industry does face a looming crisis. To some, this may seem odd; after all, advertising and subscription revenues are at all time highs. Netflix, Hulu, Amazon et al are paying quite well for the digital rights to the best shows. The major TV programming conglomerates have had great earnings over the past few quarters.

But there are dark clouds.

In his terrific monograph, Stages Of Decline, Jim Collins uses a series of case studies to demonstrate how companies that seem exceptionally successful may, in fact, already be in the late stages of decline. To elucidate, he uses a personal anecdote about his wife, Joanne. He writes about watching Joanne, a healthy and vibrant woman and athlete, easily scale a mountain pass at 13,000 feet. Two months later she received a diagnosis that resulted in a double mastectomy. At the very moment she was leaving him in her dust on a mountaintop, her body was riddled with cancer. While she appeared extraordinarily fit, she was, in fact already terribly sick. Collins uses this metaphor to show that in early stages, decline is difficult to detect yet quite easy to correct; while in later stages, it is easy to detect, yet nearly impossible to cure.

Last year, according to Convergence Consulting, more than one million cable subscribers "cut the cord," choosing to combine stand-alone broadband and a series of legal and illegal "over the top" services to fulfill their TV needs. Granted, one million cord-cutters, in the face of 106 million paying TV subscribers, hardly seem like critical mass. But ... that's more than twice the number of cord-cutters from the previous year. Even more disconcerting, 38 percent of all homes that cut the cord, did so in the past 12 months. The exodus is picking up steam.

Much has been made of how Millennials (15-30 year-olds) will change the way media is consumed. They already have. Yet, they are just the tips of the spears. The generation coming up behind them (0-15 year-olds) -- a group Magid Associations calls Plurals -- will send far more shocks through the system. While Millennials are conversant in digital technologies, Plurals are the first generation of digital natives -- they have never experienced anything but an on-demand culture.

Take these rebellious digital pioneers and their content-anywhere attitudes, stir in an excruciatingly rough job market, piles of Millennial student loan debt, and the fact that Plurals are the first generation likely to earn less than their parents; and those dark clouds get more and more ominous.

The idea of paying $100 a month for a suite of channels -- of which they use only 5-10 -- is, to these generations, as realistic as Paranormal Activity. Maybe less.

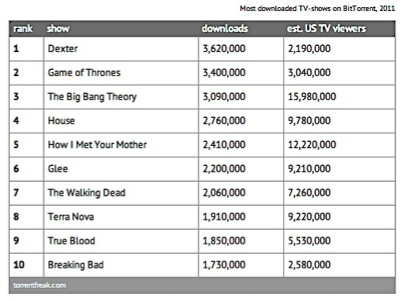

Consider this chart:

That's right, more people illegally download each episode of Dexter than actually watch the show on its network. Same for Game Of Thrones. If you included the BitTorrent views of The Big Bang Theory, its audience would grow by nearly 20 percent. For Glee, it would grow by 24 percent. These numbers are going up, not down.

Nevertheless, when you talk to programmers in the TV business, many seem to have their heads in the sand. They poo-poo the issue; point to the low numbers and dismiss them as negligible; or, they blame cord-cutting on recent economic woes and claim it will dissipate once things normalize. As recently as last week, staring directly into the face of data to the contrary, uber agent and face of the current TV establishment, WME CEO Ari Emanuel said 'cord cutting isn't happening.'

That's not just naïve, it's denial.

The current TV business is like Collins' wife -- running up the hill, full of vim and vigor, while something eats away at its insides. As the two largest generations in history continue to graduate from college and into the workplace, they will demand a low-cost, efficient alternative for pay-TV service. If need be, they will make due with the various legal and illegal "over the top" avenues for getting the TV they want. What they will likely not do is pay for 500 channels when they only use 10. And, if the industry does nothing to change, a significant number of young viewers -- the future lifeblood of the business -- will abandon the platform completely.

For those that don't believe this, please -- please -- see the music business.

But it does not need to be that way. There is an alternative. Once upon a time, Cable was the disruptive technology in the media business. The big players at NBC, ABC and CBS laughed at the idea that people would pay for TV -- especially for niche channels that only played music videos or news. And yet ... when consumers realized they could have a choice over what they watched -- more than Channel 7, 4 or 2 -- they jumped on it. Then, when the cable companies discovered (accidentally, mind you) that those pipes that they put in the ground to deliver TV also could deliver super fast broadband access, they created a catalyst of innovation that no one could have imagined (except maybe Al Gore).

The time has come for the cable industry to innovate again; to be the disruptive force from within.

Young cord-cutters will pay for TV -- look at the Netflix, Hulu Plus and iTunes as evidence. They simply cannot pay for as much TV as is minimally required in today's TV economy. So, they go elsewhere and, frankly, get a less than satisfactory experience. With a pure cut-cord experience, they miss live TV, they cannot get the most desirable shows in a timely fashion, and the act of 'grazing channels' to 'see what's on' is forbidden.

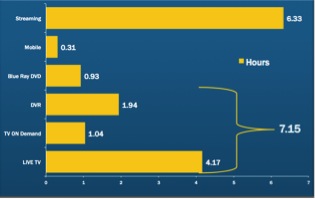

I polled the 65 students in my NYU class about how they watch TV. Here are some results:

Yes, streaming is a huge part of their TV experience. However, more than half of their TV viewing is done via pay-TV services -- either time-shifted or, believe it or not, live. In fact, when asked, the majority of the class said that the ability to plop down on their sofa and just 'see what's on TV' is still one of the most important parts of their TV experience. Remember, these are young, upscale college undergrads, living on campus in New York City -- in 2012.

What's more, IMHO, live viewing is amidst a big comeback. Seventy-six percent of all social media posts about TV shows happen while the show is airing live. This 'in the moment' water cooler phenomena is spurred by a combination of new technologies like Twitter and GetGlue; and by the deep desire among Millennials and Plurals to be part of something, while it's happening, and to not be the last to know what's going on. The 12 thousand tweets per second during the Super Bowl is one example, but so are record numbers of viewers and social media for the Video Music Awards, The Grammys and even shows like Walking Dead and The Voice.

I believe we've reached a plateau for media fragmentation and, while we will never return to the days when 67 million people watched All In The Family each and every week, I do think we will see a return to live viewing around shows of social significance -- especially if we build access points to those shows for the viewers who most want them.

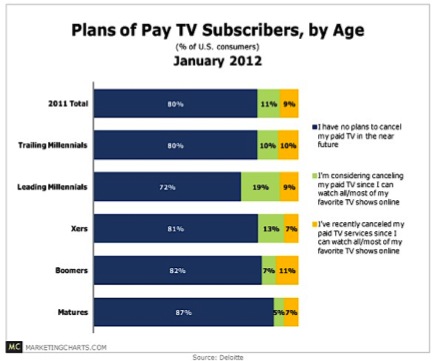

But, that does not mean the next generation of home and TV owners will blithely pay for more than they use. Here's another chart:

If, as this indicates, between 20 and 30 percent of the next generation of consumers cut the cord, the economic ramifications for the industry would be, um, bad. That's between $20 and $30 Billion (with a B) per year in lost revenues. And Deloitte's survey does not include the 0-15 year old Plurals -- who would likely answer "um, what's a pay TV service?" They won't need to cut any cords because they will never have them.

So, how does the TV industry innovate to capture the audiences they are at risk of losing forever? How do you get cutters to keep the cord? By creating a pay-TV alternative that allows them to get just enough TV to keep them happy, but not so much that they feel they are paying for stuff they don't need. By opening access to channels that they want, via the platform that is most convenient to their lifestyles.

Imagine this: A Laptop TV tier, tailor-made for cord-cutters, from the cable companies, themselves. Think about it ... 12 channels for $15, available along with your Broadband subscription, delivered via the Internet only. No remote, no DVR, no sports, no cost-intensive installation; just live TV channels and on-demand shows, streamed to your web-connected device, at a cost competitive with Netflix and cheap enough to compete with the guilty thrill of BitTorrent.

This 'Cable Subscription Starter Kit' could pull young adults into the pay-TV tent, in an inclusive way -- hooking them on the service at the exact moment they are deciding to cut their cords. Once inside that system -- once they have live TV and on-demand service -- they can compare a true pay-TV experience with the ad hoc "over the top" alternatives, apples to apples, rather than apples to really expensive watermelons. Once hooked, after they pay down their loans, garner a bigger paycheck and add dependents to their homes, there's a much better chance that they will upgrade and become the high end, HD/DVR/multi-set subscribers the industry so desires.

Granted, this is a Blue Sky idea. It was developed in my NYU class this past semester, by a group of students for their final project, which was to come up with the "next big thing" for the TV industry. The group -- Alphonse Dell'Isol, Dilara Cagal, Matthew Gorman, Arielle Moskow, Kenneth Low, Belinda Rodriguez and Wendy Tai -- wanted to develop a low cost, pay-TV subscription, tailor-made for their generation.

My feedback was that breaking up the current set top box ecology into a la carte or smaller tiers was both difficult, because existing programming deals gave programmers little incentive to go along, and inefficient, because the costs associated with delivering limited TV service were higher than could be charged for it. However, I suggested, if one could capture subscribers who would never enter the universe -- the cord-cutters -- and do so without using expensive equipment and customer service, that the viewers would be additive and costs would remain palatable. Granted, to make it entirely viable, one would need to get Nielsen to accurately measure these viewers, but C3 metrics seem to be catching up to online viewing at a rapid rate. And besides, these viewers are all currently outside the Nielsen universe -- BitTorrent downloads generate zero CPMs.

They went back to the drawing board and came back with the plan above -- a pure "over the top" tier for web connected devices, offered by the cable companies themselves. It's a low-priced pay-TV sampler designed to offer just enough TV to get a cord-cutter hooked, but not so much it competes with or cannibalizes mainstay cable packages. They call it Ditto.

A cable solution for cord-cutters, by cord-cutters.

So, why would this not happen? It's a great question. Perhaps, many in TV programming believe that the current level of pay-TV subscriptions -- $120 Billion this year -- will continue to rise forever. After all, as Ari Emanuel just said -- cord-cutting isn't even really happening.

But the industry needs to realize that the 2011 cord-cutting numbers are indeed a symptom of decline, indicative of a larger problem that is compounding daily. The disruption of the TV ecosystem has just begun. As Millennials and Plurals emerge as heads of households, the evolution will become a revolution. Unfortunately, they don't care that the very programming they love so much is totally dependent on the subscriber fees and ad rates they deride. They just want what they want when they want it, and don't want to have to overpay to get it.

Yet there is a way to stave off and even turn around the decline -- to cure what ails TV before it spreads too far. It is not difficult to avoid the fate of the music industry. But it will take bold moves, not just tweaks at the edges. It requires true innovation. 'Ditto' is just one idea -- simple, even naïve in its design. But it is the kind of constructive, disruptive thinking it takes to ensure that TV makes the transition it must to survive and thrive. If you want to keep the cord-cutters, you have to think like a cord-cutter.

Yes, TV is amidst a golden era. The programming is great. The revenues are awesome. We're running up the hill at top speed -- feeling good and looking great. But there is something eating away at the healthy tissue underneath -- it's called stasis. The good news: it's entirely treatable. But first, we need to want to be cured.