"We should consider every day lost on which we have not danced at least once."

-- Fredrich Nietsche

If on one side of the Seine this winter we've been forced to look at the dark side of Western man's capacity to reduce everyone unlike ourselves to the status of savage caricatures, on the other side of the river at the Pompidou Center I recently entered one of the most delightful and provocative shows in recent memory. It's called Danser Sa Vie, or Dance Your Life.

It is a collection of paintings, sculptures, photographs and films aimed at fusing the two great forces of modernist art: painting and dance, the first two-dimensional and static, the other passionate and ephemeral, both of them essential challenges to traditional ways of thinking about everything from desire to personal freedom to the increasingly abstract and neurological understanding of our own bodies and the necessity of rhythm in life.

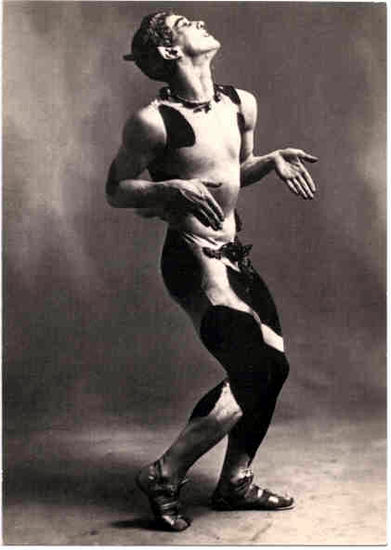

You walk in and the first thing you see is Eadweard Muybridge, famous for his moving photographs of racing horses who was equally drawn to capturing how dancers' bodies actually work. It is technical and precise. Then you turn and face a version of possibly the most scandalous and seductive dance piece of the century, Vaslav Nijinsky choreography to Debussy's music in L'après-midi d'un faune, in which the aroused, waking fawn overtakes the luscious blond nymph.

Najinsky's fawn sets the stage for Pina Bausch's version of another equally scandalous piece, Stravinsky's Rite of Spring and then for pieces by Anna Halprin in our own time and the American dance genius Martha Graham who was, fatefully, drawn to the best moments of the Russian Revolution.

Chief curator Christine Macel has a long essay on how critically intertwined the rebellious creators of modern dance were to the intellectual and psychological radicals who opened the century, not least Freud and Nietsche, or even in architecture Le Corbusier, all of whom insisted on cracking open the fixed categories of mind that until then controlled the fixed gestures of formal ballet. Nijinsky, who had been drawn to a radical subculture of rhythmic gymnastic movement, went straight to the Louvre to study the images of the nudes who whose contortions were painted on ancient Greek vases. The result, as you watch the 15 minute film passage, is to see how he transformed an art that is normally vertical and three-dimensional into a series of movements that actually seem horizontal and two-dimensional. For all the famous eroticism of his movements he appears nearly to inhabit a succession of stop-action paintings.

Until the teens and twenties, Macel says, formal dance all but denied the emotional power of human gesture. Modern dance opened a new way of understanding the union of body, mind and soul, allowing gesture to become critical for emotional expression. "Each gesture carries an emotion. That sounds very obvious to us now, but it was not the case at the time. The ideas that emotion could go through specific gesture of the body was new and I think artists were fascinated by the movement of the body in general."

Jump forward half a century to people like Merce Cunningham who maintained that all movement is at some level a kind of dance requiring at least an unconscious degree of rhythm born of our breathing patterns, the configuration of our individual joints, even the quickening or slowing of the heart beat.

A year or so ago I went to Lyon to visit choreographer Michel Eghayan who once danced with Cunningham. Eghayan works not only with his troup but also with one of the world's best known neuro-scientists, Marc Jeannerod, who has long been fascinated by what happens in the brain both as we dance and as we quietly watch dancers perform. Jeannerod and I were sitting one morning watching a rehearsal.

"All those movements are unnatural," he said. "You have to learn them to adapt your body, because it's a challenge for equilibrium. We never do that in everyday life. [It's both] mental and physical. You have to encode these movements into mental processes and then you can use your mental knowledge... most of these people, they rehearse mentally before they do the movements."

The rehearsal isn't just muscle and tendon training. It's also brain training, but of a very particular sort in a very particular part of the physical brain. He described a group of sheep farmers in Southwest France who rely on musical rhythm to carve the whistles they use for calling their flocks.

"They have a special song when they make the wood, and when the song is finished the whistle is complete. They have to go at a certain rhythm. Certain frequence, and that's what they need to do to make a whistle." Michel Eghayan overheard Jeannerod and broke in. "All that is dancing," he said.

And that brought me back to another conversation I'd had about dance with the American neuroscientist John Krakauer, who's at Johns Hopkins, who's used what he's learned about dance in the treatment of stroke patients.. If you hook up your head to the sensors of a Functional MRI screener, he told me, the parts of the brain that "light up" when you dance are the same sets of synapses associated with positive rewards and pleasure, be they chocolate cake or intense sex. What's more, he added, "Even if you're only watching dance, it's those same brain areas that show excitement."

That neuro-reality, says Christine Macel of the Pompidou Center, is science's way of confirming what Matisse, Brancusi, Nolde and Picasso were saying a century ago through the aesthetic entanglement of two-dimensional images and dynamic, rhythmic gesture.

"Sympathy neurons, mirror neurons," she says: That's why you have this pleasure in looking at dancers. It's an intense pleasure because it's grounded in your own brain and body." What she wanted to show in Danser Sa Vie is showing us how essential both the act and the witnessing of dance is to human pleasure and the making of modern art.