Time was in my backwoods Kentucky youth, you couldn't get elected president of the Student Council if you hadn't mastered sophomore biology and a basic understanding of human evolution. Certainly you couldn't then have won admission to medical school whereas today hardly any Republican candidate for the presidency dares acknowledge Darwin's contribution to human knowledge.

Had they only spend an hour in the stunningly re-newed Musée de l'Homme just across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower.

Founded in 1937 by the renowned French ethnologist, Paul Rivet, as both a research and exposition center, the Musée de l'Homme has long been among the most revered of ethno-anthropological museums, but what has always set it off is at once its collection and the going work undertaken by archaeologists, sociologists, anthropologists and even molecular biologists--an ever more complex array of hard and social scientists who under its current director Bruno David are dedicated to exploring at once our origins and our possible futures.

Or, as the museum's president Bruno David, put it for a reopening after six years of renovation, the mission is to ask, "What does it mean to be human? Where do we come from? Where are we headed?"

Though these questions appear to have little resonance with a growing sector of the American electorate, notably the U.S. Republican party members half of whom, according to in depth study by the Pew Trust, either do not know anything about evolution or reject evolutionary science as contrary to what their Sunday School teachers told them, the rest of the non-jihadist world seems to be increasingly engaged with our both our origins and our destinies. The overall question, as the Smithsonian's founders and directors, is how to engage these issues in an ever more diverse, multi-polar world.

Acknowledging that most Occidental ethnographic museums were at least unconsciously if not bluntly founded on colonialist foundations, David and his team of explorers have aimed--more or less successfully--to understand the human story through multiple refractions. Surely the most dramatic installation is a huge racial carpet at the center of the main floor that depicts the multiple diversities of human faces and experience.

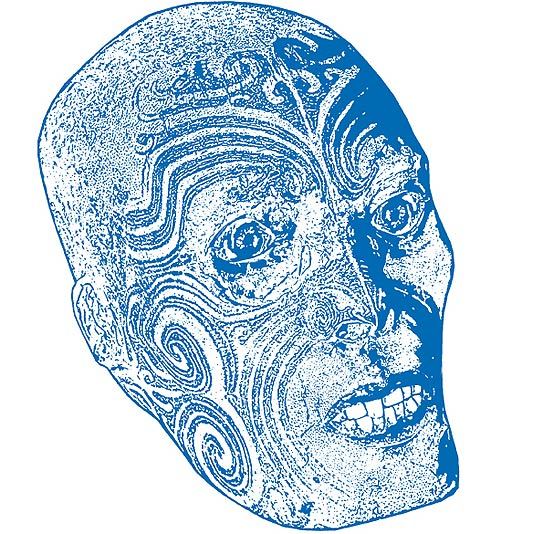

On the other hand the archaeological collections of human remains have opened difficult dilemmas around the world, whether they are of ancient Egyptian skeletons, Roman jawbones from Pompeii, fallen soldiers from World War II or the famously tattooed shrunken skulls of Maori warriors in New Zealand. Repatriation of those remains has provoked bitter battles for the Smithsonian in Washington, for the British Museum, and especially for the Musée de l'Homme, which until recently had one of the world's greatest collections of Polynesian skeletal remains.

"It comes down to a conflict between science and culture," said Vanda Vitali, an international museum consultant who frequently helped negotiate the return of Maori remains from archaeological collections. "Without these artifacts, science suffers, but who gives us the right to do our science on other people's cultures?"

Exactly that conflict erupted into a very public French battle almost a dozen years ago when the mayor of Rouen in northern France announced that he would return a large collection of Maori body parts to New Zealand--and then found that the all powerful French cultural ministry over-ruled him.

"There are other Maori heads, there are mummies, there are religious relics in France," a Culture Ministry official said at the time. "If we don't respect the law today, tomorrow other museums or elected officials might decide to send them back, too." An edict issued in 2002 declared that France considers all and any works of art as "inalienable" and therefore they cannot be returned to the lands from which they were taken in earlier colonial eras.

Further complicating the collection of what were once regarded as primitive tribal body parts was--and remains--the trafficking and profiteering in decorated or tattooed femurs, skulls, talismans and sundry sacred objects. While the Musée de l'Homme does display tattooed Maori masks, there are no actual Maori skulls in the glass cases though the skull of France's master rationalist, René Descartes.

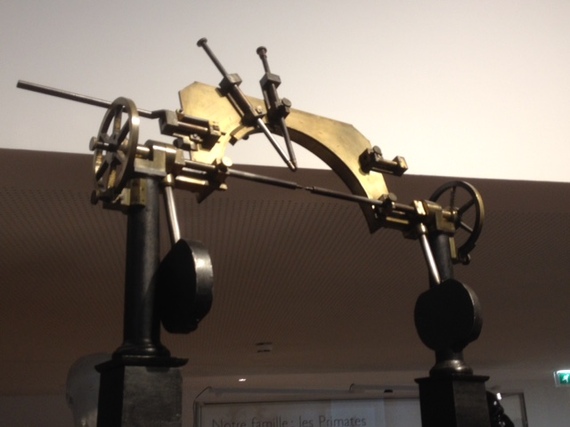

Calipers used to measure "tribal" skulls, living or dead

Science, art and colonialism all three collide in institutions like the Musée de l'Homme--issues that the latest restoration aims to address in various ways displayed in what is being called the New Museum de l'Homme--first by the displays that give no particular pre-eminence to the European past but also via continuous series of seminars that seek to address the thorny issues of colonialism and museography. At the same time, archaeological explorers continue to search the world both for greater evidence of how our evolutionary ancestors lived and how the tracking of human evolution might help us to imagine the direction in which human civilization is moving--assuming of course that we don't engage in our own collective annihilation in the same manner that British, French and American masters consciously sought to eliminate all those who did not follow our dicta.