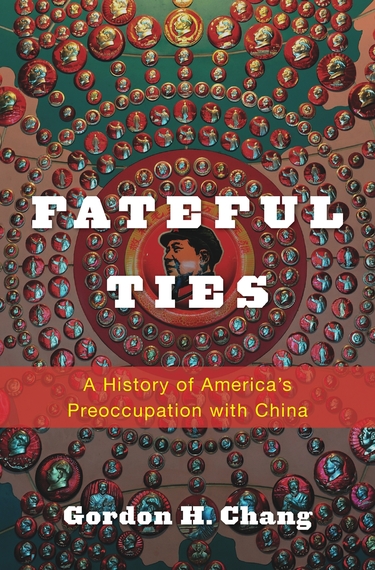

Image courtesy of Harvard University Press

My friend Gordon Chang, a history professor, has written a learned book, Fateful Ties, on the lengthy arc of US-China relations. In an era of American anxiety about what until recently was called "the Orient," his survey of the subject shows how our apprehensions endure, always underneath the surface of diplomacy and etiquette. As he observes, America is the result of the European desire for Asia.

What likely will surprise readers the most, however, is the level of personal interaction between the two societies. Although the individuals who have traversed the Pacific might not have envisioned themselves as representatives of sovereignties, they end up serving as such. The migration of Chinese to America is documented, and it has often enough been perceived as a threat -- and not without reason, as when then Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping asked President Jimmy Carter how many million Chinese the Americans wished to welcome, upon being asked about restrictions on the freedom to leave the mainland.

The Chinese examples of transnationalism are better known. Sun Yat Sen studied at the Iolani School in Hawaii and was baptized as Christian; Madame Chang Kai Shek was an English major at Wellesley who spoke with a Georgia accent as a result of having been a foreign exchange student there.

Chang shows the reverse. Motivated primarily by missionary zeal, significant numbers of Americans -- white Americans whose pedigree would satisfy any nativist -- moved to China, and some of them had children born there, who were identified for their lives as vaguely foreign when they ceased to be expatriates. Some of them, upon returning from their sojourn, were mocked as the Chinese were, even being called "chink."

An example who has been all but forgotten is Anson Burlingame. An abolitionist member of Congress, he was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln as ambassador to China. He was so well regarded, the Qing Empire turned around and made him their envoy back to Washington, D.C.

There are many others though. Henry Luce was in his day the most influential private citizen in the nation. The founder of TIME magazine, he declared "the American Century" on the eve of World War II -- as a native of Tengchow, China. Pearl Buck, also known as Sai Zhenzhu, won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938. The award cited her depiction of Chinese peasants.

The significance of China for these individuals cannot be underestimated. John Leighton Stuart, the last ambassador from the United States to China before the rapprochement of Nixon and Mao, regarded himself as Chinese. His dying wish was to be buried at his birthplace, Hangzhou, with his parents; because of the intervening political events, it took decades for his Chinese aide's American son, a retired US Army General, to fulfill the request.

Nor were all the American admirers of China white. The Black Panthers had a Maoist contingent. They embraced the "Little Red Book," studying the language in solidarity with their revolutionary comrades.

The "China hands" and contemporary alarmists may agree that American power is anomalous, measured by the long view. Yet works such as Chang's book, and Chang himself, show that what has happened is China has become American. Chang explains in an author's note at the end that he is descended from Chinese, earlier and more recent arrivals depending on the side of the family, but it is evident that he could not be more American.

His book is a major diversion, a significant accomplishment, from his great academic project: he is leading an effort to document the lives of the thousands of Chinese who built half of the transcontinental railroad. It was the Chinese, absent from the photographs of the Golden Spike ceremony of 1869, who realized Manifest Destiny.