Your data is telling a story about you. Maybe the story's a good one: you vote at every election, you pay your bills on time, you do your job well and get to work on time each day. But there are now so many data brokers -- buyers and sellers of data -- that databases may be defaming you without you even knowing it. Consider the following examples:

1) You could get classified as a meth dealerChoicePoint is a data broker that maintains files on nearly all Americans. It mistakenly reported a criminal charge of "intent to sell and manufacture methamphetamines" in an Arkansas resident's file. ChoicePoint corrected the information when notified about the error, but other companies that had bought Taylor's file from ChoicePoint did not automatically follow suit. The free-floating lie ensured rapid rejection of her job applications, and she could not even obtain credit to buy a dishwasher. Some companies corrected their reports in a timely manner, but Taylor had to nag others repeatedly and even took one to court.

She found the effort to correct all the meth conviction entries overwhelming. "I can't be the watchdog all the time," she told the Washington Post. It took her four years to find a job, even after the error was uncovered, and she was still rejected for an apartment. Taylor ended up living in her sister's house and says the stress of the wrongful accusation exacerbated her heart problems. As Elizabeth DeArmond has observed, the "power of mismatched information . . . to disrupt or even paralyze the lives of individuals has grown dramatically." For every Catherine Taylor -- who became aware of the data defaming her -- there may be thousands of other victims entirely unaware of dubious scarlet letters besmirching their digital dossiers.

2) Buy cable "plus package," get classified as plus-sizedHealth status can be attributed (if not definitively discovered) with reference to records from far outside the medical system. If you're a childless man who shops for clothing online, spends a lot on cable TV and drives a minivan, we know certain data brokers are going to assume you are overweight. Recruiters for obesity drug trials will happily pay for that analysis, and that could lead to some good health outcomes for the people they reach. But how far might the data go?

3) Watch out for that coffee cup! The Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues issued a report in 2012 that brought up some of the novel threat scenarios involved in probabilistic analyses of genomic information:

In many states, someone could legally pick up a discarded coffee cup and send a saliva sample to a commercial sequencing entity in an attempt to discover an individual's predisposition to neurodegenerative disease. That information might then be misused, for example, by a contentious spouse as evidence of unfitness to parent in a child custody case. Or the information might be publicized by a malicious stranger or acquaintance without the individual's knowledge or consent in a social networking space, which could adversely affect that individual's chance of finding a spouse, achieving standing in a community or pursuing a desired career path.

Even more bizarrely, malicious gossips may claim First Amendment protection for spreading such information. As long as it's true, there's very little you can do to stop them.

The coffee cup example may seem speculative. But translated to the digital world, it's a business model for many big companies. As Anil Dash has observed:

Someone could make off with all your garbage that's put out on the street, and carefully record how many used condoms, pregnancy tests or discarded pill bottles are in the trash, and then post that information up on the web along with your name and your address. There's probably no law against it in your area. Trash on the curb is public. . . . [Online,] the business models of some of the most powerful forces in society are increasingly dependent on our complicity in making our conversations, our creations and our communities public whenever they can exploit them.

We now need to consider whether the types of social norms that keep companies from picking up trash bags and analyzing their contents should also apply to our online lives. The "digital exhaust" from internet use might be just as embarrassing and largely irrelevant to society as the refuse in our waste baskets. And just as no one should be forced to move to a building with an incinerator to keep their trash private, so too might we want to live in a world where there's no pressure to keep up with the latest in encryption technology to keep one's secrets.

4) A depressing use of pharmacy dataCompanies are not shy about using and distributing certain information. For those in the individual insurance market, the risk of runaway health data has already been realized. Patients who purchased antidepressants were later denied insurance repeatedly, thanks to a dossier sold to insurers.

Consider, for instance, the plight of a Louisiana couple who sought insurance while in their fifties. Paula had taken an antidepressant as a sleep aid and occasionally used a blood pressure medication to relieve some swelling in her ankles. Humana, a large insurer based in Kentucky, refused to insure the couple based on that prescription history. They were not able to find insurance from other carriers, either. No one had explained to them that a few prescriptions could render them uninsurable. Indeed, the model for blackballing them may still have been a gleam in an entrepreneur's eye when Mrs. Shelton obtained her drugs. The Affordable Care Act makes things better now, since health insurers cannot deny coverage for preexisting conditions. But who knows who else is using such data?

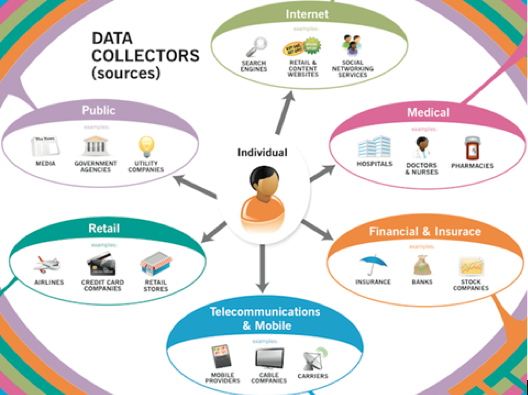

5) Get tracked by many different sources One thing is becoming clear with data brokers: it is almost impossible to keep track of where they're getting their data. Consider all the sources that could collect "health-inflected" information, such as bills for pills or GPS records of an emergency room visit:

And how far data brokers could go to combine and recombine those sources:

Images Credit: Federal Trade Commission

Images Credit: Federal Trade Commission

Keeping track of all these uses of data is nearly impossible -- it could turn into a full time job.

6) Opportunity -- and peril -- on new social networks

Social networks can now be organized around personal health records. One is PatientsLikeMe, which provides novel and powerful opportunities to address health issues and to form communities, but also opens the door to other data uses. While addressing frequently asked questions, PatientsLikeMe has stated that "you should expect that every piece of information you submit (even if it is not currently displayed) may be shared with our partners and any member of PatientsLikeMe." While the company might be relied on to vet partners, its customers may have no idea about how easily information can spread. The Wall Street Journal reported that "Nielsen Co., [a] media-research firm . . . was 'scraping,' or copying, every single message off PatientsLikeMe's private online forums." Health attributes connected to usernames (which, in turn, can often be linked to real identities) could have spread into numerous databases. Many are not required to report to any entity on either the origin or destination of their data.

7) Perplexing personality testsIn an era of persistently high unemployment, even low-wage cashier and stocking jobs are fiercely competitive. Firms use tests from companies like Kronos, Inc. to determine who would be a good fit for a given job. You may be penalized for only agreeing "strongly" rather than "totally" in response to this statement: "All rules must be followed to the letter at all times." Consider how you might respond to statements like these, given four possible multiple-choice responses: "strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree:"

•You would like a job that is quiet and predictable•Other people's feelings are their own business•Realistically, some of your projects will never be finished•You feel nervous when there are demands you can't meet•It bothers you when something unexpected disrupts your day•In school, you were one of the best students•In your free time, you go out more than stay home

What is the right response for a would-be clerk, manager or barista confronted with these statements, which come from recent tests? It's not readily apparent. Moreover, the tests' authors refuse to release the "right answers," and who knows if they could. Companies like CVS and Circuit City may want different attitudes from different staff. Despite its indeterminacy, the test has important consequences for job seekers. Test takers with a "green score" have a decent shot at full interviews; those in the "red" or "yellow" zone are most likely shut out.

A glimmer of hope...

Although the new data landscape is scary, it makes sense to use some existing ways of protecting yourself. For example, under HIPAA, you can at least demand to see your medical records. You even have the right to see whom your health providers disclosed them to. Similarly, with FCRA, you can try to assure that your credit records are accurate. And you can order copies of your credit report from annualcreditreport.com. You can find out where other files about you are kept by consulting this site, maintained by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

But even in these areas, it pays to be careful! For example, after federal law required credit bureaus to release a free copy of credit histories to consumers annually, credit bureaus created a number of websites with names like "freecreditreport.com" which ultimately charged for the report, or only released it when the requestor bought other services. Forced to establish the site www.annualcreditreport.com to release credit histories, the bureaus "blocked web links from reputable consumer sites such as Privacy Rights Clearinghouse and Consumers Union, and from mainstream news web sites," according to one complaint. Enforcers at the Federal Trade Commission had to intervene, and sued when bureaus made their call centers difficult to reach. Even when data is regulated, it pays to be very careful in how you access it.

Unfortunately, most data isn't covered by FCRA or HIPAA. So we're going to need new laws to help rein in the worst abuses of the new data landscape. Data brokers need to document where they get their data from, and to whom they sell it. We deserve the right to access all files kept on us and the right to correct them. Until that happens, the brave new world of runaway data will continue to threaten our reputations, opportunities and livelihoods.