Fifteen months after the Berlin Wall fell, the communist party in Albania still ruled. But student protests 25 years ago this week kicked the regime to its knees.

Excerpted from Modern Albania: From Dictatorship to Democracy (NYU Press, 2015)

Sparked by student protests, crowds toppled Enver Hoxha's statue in Tirana on February 20, 1991. © Gani Xhengo

The Berlin Wall had fallen and Germany was reunited. Across Eastern Europe, communist regimes had toppled one by one. But in tiny Albania, the Stalinist state on the Adriatic, the Party of Labor was holding on. Demonstrations had forced the legalization of pluralism in December 1990 and a major opposition group, the Democratic Party, had sprung to life. But the new party's leaders mostly came from the political elite and many Albanians found the change too slow.

Young people in particular hungered to rejoin the world after decades of isolation and abuse. They wanted to travel, wear jeans, and listen to "decadent" western music, all of which was forbidden under the strict Stalinist code. Students craved to study history, art and literature beyond Marxist-Leninist constraints.

The newly formed Democratic Party, however, was taking a cautious approach, meeting regularly with the communist leadership to consult. Former political prisoners, recently released from their prisons and work camps, also complained. When DP leaders visited Shkoder to set up their local party branch, the Catholic priest and former prisoner Simon Jubani told them bluntly: "We forgive you for being communists, but now get in line."

The DP leaders Sali Berisha and Gramoz Pashko countered that Albania needed a serious party. Like President Alia, they argued that Albania's lack of democratic traditions demanded respect. It was irresponsible and counterproductive to move too fast.

The moderate-radical paradigm did not fully explain the behavior of those involved. While two basic camps emerged, the individuals in those camps shifted their positions depending on the circumstances. Perhaps more than anything, the driving factor was not ideology or strategy, but the power struggles within the group. The Democratic Party of Albania was not Solidarity in Poland or Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, which had confronted communism on principle. The party founders were not dissidents who had challenged power at personal expense.

By February 1991, the students' patience had worn thin. The euphoria of pluralism had dissolved in the Democratic Party's watery approach to the state. Berisha, Pashko, and the others were too complacent, some students said, and it was time to push.

On February 5, the electricity died at the Institute of Agriculture on the edge of Tirana, and a group of students demanded that the dean resign. The dean refused and the students declared a strike until living conditions improved. When morning broke, the protest grew, with students joining from Enver Hoxha University. By midday, another crowd had gathered in Student City. As speakers took the mike, the list of demands grew: if living conditions for students did not improve, the government must resign.

The next day, the students in Student City formed a committee, which sent a public letter to the prime minister elaborating on the agricultural students' demands. ["A Letter of the Students to Adil Çarçani, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers" (in Albanian), Rilindja Demokratike, February 7, 1991.] After demanding better heat, paved roads, and a disco in Student City, the students called for "freeing the school from ideology." Then came the most delicate ask: to remove the name Enver Hoxha from the school and call it the University of Tirana. If the government did not meet these demands, the letter said, then it should resign.

The call to remove the dictator's name was strategic and charged. The students meant to strike at the symbolic heart of the regime. They wanted to convey a message, especially to the rural areas, that communism had died.

The government rejected the students' demands. Ramiz Alia had personally presided over the university's naming ceremony in 1985, dramatically pulling aside a curtain to reveal "Enver Hoxha University" engraved on the wall. Removing the name would insult Albania's past and its citizens, he said. To the students' dismay, the Democratic Party leaders agreed. They feared provoking the regime and its conservative wing. The party had promised Alia that it would participate in the first elections later that month peacefully and with respect for the law. They also thought a strike would take crucial time away from the electoral campaign.

"We thought if we create problems then we'll have trouble for breaking the rules," Gramoz Pashko explained to me in 2001 from his living room where the DP founders had drafted the party platform eleven years before. "Symbolically their actions were good, but it may have diminished our support because it gave the impression that change will come with chaos and anarchy."

In the end, the DP could neither stop nor oppose the students, so it walked a middle line by proposing a referendum to remove Hoxha's name. "The Democratic Party believes that stability cannot be attained by closing our ears, objecting to or denying the request of the students to remove the name of Enver Hoxha from the University of Tirana," a carefully worded statement said. "Fulfillment of the students' request through a referendum of the students and staff of the university does not affect the figure of Enver Hoxha as the leader of the Party of Labor of Albania." ["First Meeting of the Democratic Party" (in Albanian), Rilindja Demokratike, February 16, 1991.]

Student City's street theater grew larger by the day. The students used a metal microphone connected to speakers stacked on a wooden table to amplify their calls for pluralism and reform, often interrupted by raucous rounds of "Freedom, Democracy" or, more pointedly, "Down with Enver!" They told jokes and mocked the regime. The art student Blendi Gonxhe played master of ceremonies, sarcastically reading poetic tributes to Enver in front of a hand-painted sign that said "Give Peace a Chance."

"The crowd was like a laundry," Gonxhe recalled ten years later in his Tirana City Hall office, where he was working as deputy mayor. "They came to clean themselves."

Students took the mike to express their frustrations and dreams. "During spring break, the students in Western Europe go skiing in the Alps," a student from Tropoja said, as a friend held the microphone to his lips, according to a video from that day. "But the Albanian students ask for a meeting with the prime minister."

"We have eight political parties and all of them are compromised by the communist party," proclaimed Shinasi Rama, referring to the other parties, such as the Republicans and Social Democrats, which had sprung to life after the DP. "It's a fictitious pluralism."

The newly established Independent Trade Union would declare a general strike if the students' demands went unmet, a representative announced. A spokesman from Enver Hoxha Factory showed a petition with two thousand names calling for their workplace to be renamed the Tractor Factory. The student and DP official Azem Hajdari also came, wearing his fashionable white trench coat. "Dear brothers and sisters," he said, according to the video. "Thank you for allowing us to go around in cars."

Government officials came too, like Minister of Education Gjinushi, who tried to focus the crowd on economic demands but was repeatedly interrupted by shouts: "Remove the name! Remove the name!" He met the strike committee and offered them better physical conditions if they dropped their demand to change the name. But the name change represented the movement's heart.

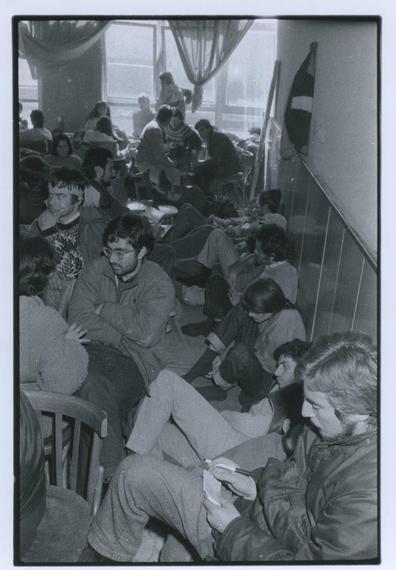

Students enjoy speeches at an anti-government demonstration in Student City, Tirana, February 1991. © Gani Xhengo

For ten days, both sides refused to budge. The student protest grew larger and the government stressed that the name and work of Enver Hoxha "belongs to the whole people." ["Statement of the Council of Ministers" (in Albanian), Zëri i Popullit, February 19, 1991.] Reflecting on the students' strike years later, Ramiz Alia said that it worried him a lot. "They were young people who did not know what they were doing," he said. "Their demands would incite conflict." Hoxha was sacrosanct and party bosses in the provinces were already complaining that the party leadership had lost control. Word of a nebulous organization called the "Volunteers of Enver," ready to defend the system, had reached Tirana.

Unfazed, on Friday, February 15, the students took another step. A thick, wet snow fell on Student City, dotting the crowd's black umbrellas with heavy flakes. Blendi Gonxhe announced that the government must remove Hoxha's name by noon on Monday or the students would begin a hunger strike. The government did not bend, so on Monday at 11:30 a.m., hundreds of students lined up outside the cultural center in Student City. Seven hundred and twenty-three people signed their names to the strikers' list, kissed the Albanian flag (without the communist star), and stepped inside the center, among them a handful of professors. Guards turned away many more due to lack of space. They locked the door and one student kept the key with him in the attic, where the organizers had hidden some rusting knives, machetes, and hand guns from World War Two, more for symbolism than practical use.

"Parents, brothers and sisters," a defiant declaration from the students' organizing committee said. "With determination and without pain we tell you that we won't return as before to our family homes. We won't even return in the evening. Maybe you will miss us for days and we are confident that this absence will make you proud." ["Declaration of the Organizing Commission of the Student Movement" (in Albanian), Tirana, February 18, 1991.]

The first hours were fun. The strikers lounged on the floor, smoked cigarettes, played cards, and danced to ABBA and the Dire Straits. Some wore bandannas on their heads, like kamikaze pilots. On the wall someone wrote in red letters: "Enver = Hitler + Stalin + Al Kapone + Pol Pot." The students shared a sense of purpose and solidarity. Then the police sealed off Student City.

"The first hours were enthusiastic, euphoric you might say," recalled Edvin Shvarc, one of the students in the hunger strike. "But when they sealed it off, there was a grave silence."

* * *

That night the DP Steering Committee met to discuss the crisis. They decided to see President Alia, as they had done a number of times over the past two months, and selected four people for the task: Sali Berisha, Azem Hajdari, Eduard Selami, and Preç Zogaj. Alia agreed to meet right away.

The delegation found the unflappable Alia in a nervous state, Selami and Zogaj separately recalled. He was a control freak and got upset when things slipped out of control. As they entered the president's office, he was speaking loudly on the phone with his back to the door, threatening to declare a state of emergency. "I won't let Albania slide into chaos," he shouted into the phone. The DP members were shocked, thinking Alia was giving orders to the military.

Alia hung up the phone, turned to his visitors, and shook their hands. They sat and noticed that another man was already in the room: Sabri Godo, head of the small Republican Party, which was created after the DP, many think at Alia's behest. Alia turned to Godo and asked whether he had a hand in the student strike.

"No," Godo said.

"And you?" Alia asked the DP reps.

"Yes, we do," Azem Hajdari replied.

Then you should go to the students and deal with them yourselves, Alia said. Otherwise you will be responsible for the consequences. He asked the DP to use its influence with the students to get them out of the strike and to have them drop their demand for a change of the university name. Only parliament could change the name, he insisted. The students and professors should hold a referendum, as the DP had proposed, and parliament would comply.

The DP visitors said a referendum did not meet the students' demands, and that they could not convince the students to stop the strike. At this point, the men were surprised to see Education Minister Gjinushi enter the office through a discreet door in the corner that, they learned after coming to power one year later, leads to the hall and a presidential bathroom. Had Alia's advisor been there all along?

As a compromise, the crafty Gjinushi proposed that the government "reorganize" the university into four parts and, as part of that reorganization, officially change the name. The DP members agreed to present the students with his idea.

Around 2:00 a.m., the DP delegation went to the striking students, who were sleeping, resting on blankets, or playing cards. Their answer to Gjinushi's proposal was an adamant "No!" The government must declare the name Enver Hoxha removed, they demanded. "Don't use the students to make any compromise that will help you win the election," a student said as the DP leaders walked out. ["Political Diary: Three Days to Overthrow Three Statues" (in Albanian), by Mitro Çela, Rilindja Demokratike, February 23, 1991.]

For two days, the students survived on water and cigarettes, though some accepted the food and drink that sympathizers slipped in. "No Tirana parent would let their child go hungry," Gonxhe said. Outside thousands of people gathered to show their support. Workers from Tirana and miners from the mountains gave speeches. People walked more than thirty miles from Kavaja. On the third day, a student in the strike had an epileptic fit and a medical team carried him out on a stretcher, although some former students told me they staged his seizure to mobilize support. Already angry and nervous, the crowd began to chant. An actress named Rajmonda Bulku took the microphone and urged women in the crowd to march. "Let's go in front of the television, mothers and sisters," she said, according to a video of that day. "Let's gather and make a protest march in solidarity with our friends or children, with our brothers and sisters."

Women in the crowd began to move.

"The crowd was terribly tense," Bulku recalled in an interview she gave on the tenth anniversary of the strike. "They were waiting moment to moment for something to happen. . . . The crowd wanted you to say something to move them." ["Who Toppled the Statue in Tirana, Interview with Rajmonda Bulku" (in Albanian), Albania, February 21, 2001.]

The women marched and the men followed. The trickle turned to a stream and soon an angry river flowed from Student City down Elbasan Street, past the High School of Arts, where the police had blocked the students on December 9. Green police trucks with hoses and water tanks blasted the marchers with water, forcing them past the state radio and television building, behind the Hoxha museum in the pyramid, and onto the boulevard. Riot police and water cannons waited there to defend the sacred Block where the political leadership lived and to divert the crowd down the boulevard to Skanderbeg Square.

The police action was a physical manifestation of Alia's political strategy since 1989. Albanians' desire for change had swelled like a wave, and no wall could withstand that force. Rather than build a useless defense, Alia channeled the flow into areas that could be managed and controlled.

Security forces waited in the square. Thousands of protesters milled about, some throwing rocks, thinking of Tiananmen Square, while looking at the thirty-foot-high bronze statue of Enver Hoxha, taller still atop his granite pedestal, standing like a lightning rod in a storm.

A crowd surged, was repelled by the police, and surged again, gaining confidence as its numbers grew. Proud and determined, Hoxha looked out over the square wearing a suit and long coat, with his left hand behind his back and right hand at his side. The crowd pushed. A boy climbed Hoxha's coat and hooked a metal cable around the dictator's thumb. Men pulled from the left, while others pushed from the right, and the Leader's body began to tilt from side to side. Just after 2:00 p.m., it separated from its base and came crashing down, predictably, to Hoxha's left.

For documents, photos and excerpts from the book, please visit the Modern Albania webpage.