Is there a direct correlation between being a seven-year old fan of a highly principled superhero and becoming an adult with a keen sense of loyalty to an accomplished and progressive political candidate? Or even to becoming that candidate? I know of no study conducted to show that there is. But while I have yet to ask a candidate running for office this question, I have asked numerous acquaintances who have been enthusiastically engaged with one or more political campaigns, and nearly all of them can name a superhero who had in childhood helped to instill in them a sense of ethical rightness and dedication to humanity -- the kind of qualities they now look for in political candidates running for public office. I will return to this point at the end of this post, but keeping it in mind may help to resonate the other strains of thought passed through on the way.

*********

2016 is the year that Wonder Woman turned 75. Or perhaps we should say that she is 75-going on-2,500. And that is on the young side of the guestimate, given that Princess Diana's origins are premised on a partly mythological, partly historical race of Scythian Amazon warriors dating to at least 500 BCE. Some sources would have us date women's matrilineal and matriarchal rule much further into the Neolithic millennia, or even the Paleolithic centamillennia, given that the evidence of a devotion to the female form in art appears to extend further back into prehistory than we can possibly know. Yet, despite her ancient stature, Wonder Woman remains the most mythopoetically potent and popular contemporary superwoman to grace contemporary culture, especially among girls and women who claim her as an early feminist inspiration. And this despite that she wears, what New York Times writer Vanessa Friedman dissed, 'a bathing suit'.

That's mythopoetic -- the making of new myths -- especially those myths that are reflective of the generations and cultures of the day. While often embodying a newly-formed political position, often even a dissent against some earlier and perceived custom, tradition or ideology presiding among a community, especially one that is seen to be outdated or repressive, mythopoetics disseminate the values of new social orders that are enlightening, liberating, even empowering. For instance, Wonder Woman has for decades been mythopoetic of feminism, independence, strength, and in some circles, bisexuality, if not lesbianism.

Wonder Woman's appeal beyond popular culture can be attributed in part to her survival, often her flourishing, in a medium predisposed to male homosocial codes and activities. Princess Diana's background, as opposed to her secret American identity as Diana Prince, implied the broader cultural politics of a matriarchal society without men, while having allowed discreet glimpses of lesbian and women's homosocial culture long before such views could be publicly and legally acknowledged. But Wonder Woman's heterosexual inclinations also come into play in her affections for Steve Trevor, a narrative sideline that further facilitates her entry to and respect from the mainstream Western culture while helping to integrate the backdrop of her alternative sexual choices into a young person's spectrum of acceptable cultural lifestyles. In short, by honoring amazon sexuality and sociology that for centuries had simultaneously been in disrepute, and making them a part of the norm, from her first appearance in 1941, Wonder Woman's ambiguous sexuality has indicated that a notoriously censorial social order was slowly being supplanted. Creating a new norm is what mythopoetics do. And when the new myths being advanced are hybrids of the fantastic and the proscribed, then usually the mythopoetic at hand indicates that an entire belief system is being overturned for its past complicity with widespread suppression of cultural choices.

It is such mainstream mythopoetics as graphic novels, animated films, science fiction and other popular forms that since the 1960s generated the profusion of spectacular activist myths of LGBT-identified vampires, multiracial mutants and cyborgs, and ecological elementals that have been crashing the narratives of the mainstream culture since the 1960s. And so often it is the most pervasive, fantastic, technological and hormonal myths that have the greatest impact on societal reorganization, such as the cultural war being waged between progressives and conservatives in the 2016 US Presidential Race.

But Wonder Woman represents a new social order extending far beyond American and even Western models of the distribution of power. As one of the most popular and earliest of contemporary mythopoetic models, Wonder Woman stands in stark contrast to the dominant patriarchal mythologies that since the Bronze and Iron Ages promoted narratives in which men alone ruled and fought the decisive battles. If the myth of Amazons resisted heterosexual trends while relishing homosocial fidelities, it is perhaps in large part because images and sculptures of evidently revered women have been fashioned at least since the early Neolithic period (10,000 BCE), during which certain settlements retained matrilineal, if not matriarchal, social orders. It is with the Bronze and Iron Age societies (2500-500 BCE) that invented and spread the use of heavy weaponry and increased the wealth of the patriarchies through warfare that enabled male representations to gradually displace those of matriarchal societies -- or so goes the feminist speculation on social history.

No modern super hero has been more emblematic of this historical shifting of status on both sides of the gender divide than Wonder Woman has been since her introduction in 1941. For that matter, it's an insult to say that Wonder Woman was solely the creation of a man. It's true that she was first written by the American psychologist and writer, William Moulton Marston in collaboration with the artist H. G. Pete, but with his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston. It has been only in recent years revealed that Princess Diana's physical appearance was modeled after the Marston's mutual live in lover, Olive Byrne, a relationship that reaffirms the rooting of Wonder Woman in the lesbian and bisexual lifestyles of the original Scythian women warriors. We've also learned that Marston had a woman assistant, Joye Hummel Murchison, who from 1944 to 1947 scripted dozens of Wonder Woman stories. And with Wonder Woman's veiled lesbian inspiration came a radical feminist mythopoetic component that the Marstons derived from their friend, the feminist organizer, Margaret Sanger. So that's Elizabeth Holloway Marston, Olive Byrne, Joye Hummel Murchison and Margaret Sanger: four presumably feminist women surrounding the one man credited with originating the most enduring and endearing popular feminist icon. Knowing this, how can we continue to give Marston all the credit? And although it may seem puzzling that a woman superhero hailing from a segregated race of women warriors would be elaborated in a medium geared to the tastes of adolescent boys, we should remember that Wonder Woman was created at the time of the US entry into the Second World War, which explains why adolescent girls were suddenly being targeted for patriotic development through the imagery of a warrior woman through the newly-popular superhero genre.

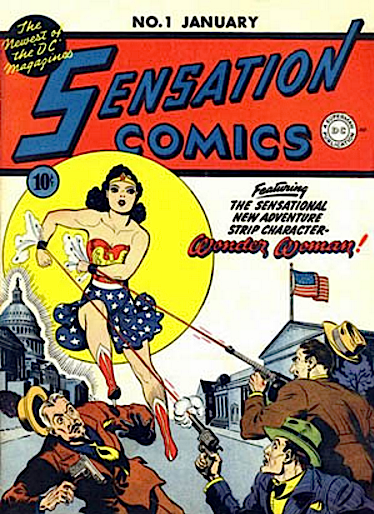

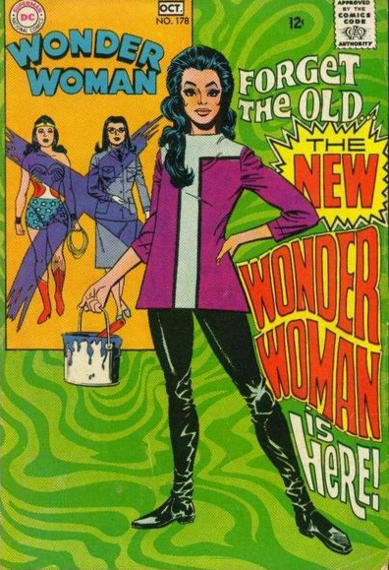

With Wonder Woman's fist appearance in All Star Comics #8, December 1941, and her first cover on Sensation Comics #1, January 1942, the Wonder Woman creators responded to the call of American patriotism and the lure of the bathing suit to make Princess Diana a bolster to the morale of US troops overseas. This accounts for both her star-spangled skirt and her eagle-emblazoned halter. Not long after, her spangled tight briefs designed to the contours of 40's swimwear ensured Wonder Woman would remain a distraction from the incivilities of war for the young men fighting it. Yet even before the more overt feminism of Princess Diana's origins would be toned down in the conservative 1950s, and her lesbian tendencies altogether suppressed after the Marstons' departure, she would, like Supergirl, be marketed blandly by DC Comics as little more than a feminine version of Superman, voided of much of her original and uniquely amazonian characterization.

Yet even in the 1950s, Wonder Woman's anchoring in the mythological women warriors could never be completely blacked out, given that her origin is derived from no less than the 4th-century chronicler, Herodatus, "The Father of History", who located the Amazons' territory northeast of the Black Sea. For two millennia they had been considered to be mythological larks, while the Greek and Roman friezes depicting the Amazons' defeats were thought to be instructive that women could never successfully rebel against men. That the battles were uprisings was not mentioned in the narratives nor interpreted in the friezes. In the literature and drama, the women Furies of Greece would never again be portrayed as they had last been in The Orestia by the Greek dramatist, Aeschylus in 451 BCE, and in the political comedy, Lysistrata, by Aristophanes in 411. From the fourth century BCE on the Amazons and other rebellious women were explained away as the handed down dreams of discontent women. But the women of Greece who silently knew better, secretly held onto a past that their mothers told them had been matrilineal, if not matriarchal.

Their silence was broken in the 1990s when archeologist Jeannine Davis-Kimball brought to light a new historical relevance to Wonder Woman and her Amazon mythos when she excavated several burial sites of women warriors beneath the mounds of Scythian territory northeast of the Black Sea, the very region where Herodotus tells us the Amazons lived. The graves, as well as fragments of clothing that Davis-Kimball matched to those found painted on vases in the Munich Antiquities Collection dating to 400 BCE confirm the correspondence with truly historic women warriors and their peace-time societies. Suddenly Wonder Woman became symbolic of a living, heroic, matriarchal history .

Whether we choose to believe that the Amazons are mere myths or were real women warriors and politicians will impact on the degree to which we regard the feminist mythopoetics of Wonder Woman's narration to be indicative of a desired and implemented dissent and social activism against the male-dominated social orders of our own time and place. Either way, Wonder Woman's own origins and subsequent representation, as relegated by DC Comics, reflects the tug of war pulling at Princess Diana by opposing gender interests throughout her 75-year ethos, as it did over the 2500 years of Amazon legend and history.

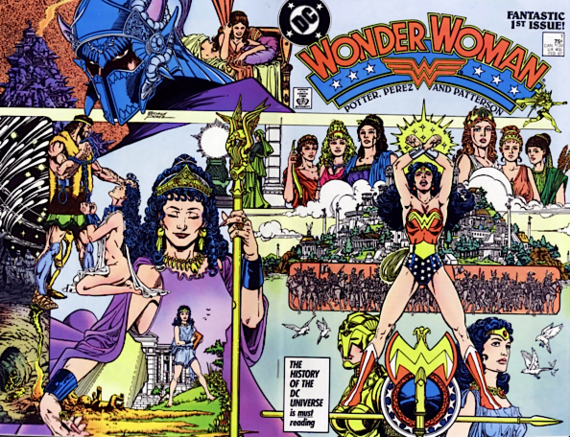

In the world of Western Superhero Comicdom, that tug of war shifted in favor of feminism in 1987, with not only Princess Diana's revitalization, but the politicization of Wonder Woman's entire Amazionian mythos by D.C. Comics' legendary artist-writer, George Perez. Perez crafted what is perhaps the most successfully and long-lived superhero narratives in terms of feminist political mythopoetics. He not only explored and revitalized the debates of feminism and patriarchy, pacifism and militancy, and separatism and solidarity that her origin among the Greek Amazons and goddesses long implied, he allowed hints of lesbian affection to characterize Wonder Woman's amazon sisterhood, what with their island of Themyscira being an invisible place of women only, and on which no foot of mortal man could ever set. It was a legacy that women writers and artists would join for the first time, with such names as

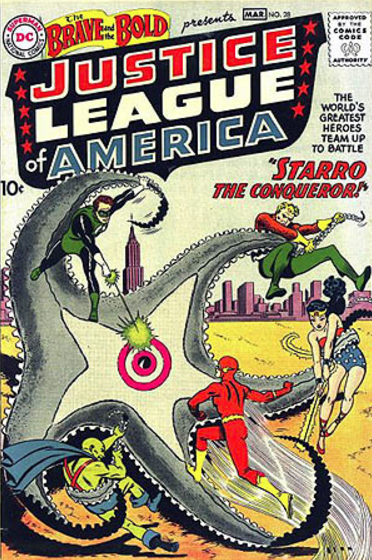

Whether Wonder Woman's narration veered toward super-tokenism or super-activism, D.C. Comics' 1990s revitalization of the Wonder Woman mythos was to coincide with the revitalization of the mythopoetics of Superman, Green Lantern, and Marvel Comic's X-Men. In the 1980s, The X-men took the lead in feminist superhero branding for being led for years by the mutant African woman named Storm, whose origin story includes her worship as a tribal nature goddess. More substantially, Storm's creators through her sought to disseminate the principles of racial parity, just as superhero creators had done with T'Challa, the Black Panther, who in 1966 became the first black superhero, and would later do with Green Lantern John Stewart, the first African-American inducted into the Green Lantern Corps, and Cyborg, of the Teen Titans. There is little doubt that the cultural parity that such black superheroes instilled in young readers in the 1980s and 1990s resonated throughout their adult lives. Perhaps it is hubris to think they directly contributed to the historically-pivotal election of Barack Obama in 2008 as the world's most powerful leader. But they did contribute to the larger popular culturation that African-Americans accumulated and grew on their own in music, film, literature and theater.

Ironically, with such powerful women superheroes as Phoenix, Rogue, Supergirl, Storm, and She Hulk inspiring dozens of other diverse super women to follow, the mythopoetic high water mark forced even the scripters of Wonder Woman to rise to and keep Princess Diana apace, especially in those areas of her narration where she seemed bogged down in antiquated tropes and costuming, what with her star-spangled red, white and blue associated by global readers with American Exceptionalism.

The debut of Gal Gadot, the Israeli actress and model, in the Wonder Woman role in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice is one step toward making Wonder Woman as global a figure as her historical roots brand her. The new, darkened hues of her costume are also in the style of The Dark Knight, along with the trailer for her 2017 film, Wonder Woman revitalizing interest in the Amazon Princess among boys and young men to a degree not seen since Perez launched his series in 1987. Although audience response to her new look has been mixed, the piqued interest in her reemergence in the entertainment industry suggests that Princess Diana's mythopoetic import will be significantly extended even if it is only as a superhero, though DC has been touting it will also be as a feminist, and activist, and an Amazon. But will this be enough to keep Wonder Woman at the top of the superhero heap?

In the last three decades, in film, as in graphic publications, a variety of women superheroes have caught up with, if not surpassed, Wonder Woman's dissemination of feminist politics and dissent into the graphic and cinematic mainstreams, even if more discreetly or in ways more friendly to male readers. Among movies, the most mythopoetically profound reformation of the feminist hero both in terms of contemporary popularity and as profound, hisotrically-rooted myth can be found in the Alien quadrilogy, that begins with Ridley's Scott's groundbreaking Alien (1979), and evolves majestically with James Cameron's Aliens (1987), David Fincher's Alien3 (1992), and Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Alien Resurrection (1997). Together, the four films transform the courageous and calm woman warrant officer-turned-combatant, Lt. Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, into a near-religious savior in the image of Perseus, Christ and the Buddha. Ripley is the only hero to survive three, and perhaps four films because of her foresight and disciplined-if-intuitive defenses against a brood of rapacious extraterrestrial xenomorphs in a series of horrifically-pitched battles that on a mythopoetic level embody the genocidal extremes to which the bipolarization of "the self" against "the other" can lead.

Unlike Wonder Woman, Ripley appeals to men as much as to women because she wears her political status as a woman-equal quietly-yet-assuredly. But the mythopoetic bipolarization of the self-vs-the-other churns more deeply through mythological depths that are excavated differently by each of the four directors. Yet together they chart out the symbolic character arc of Ripley from her introduction as the sacrificial virgin of an intergalactic industrial corporation (Alien); to a matriarchal warriror (Aliens); to a martyred hero (Alien 3); and ending as a resurrected legend and messiah come to Earth (Alien Resurrection). At the same time, Ripley confronts two social myths representing deeply repressed sexual and psychological anxieties that have marked all cultures and civilizations. The first is the more general anxiety that individuals have been made to feel about their bodies and their functions, and which arguably originate with the archaic outlawing and repressions of aggression and pleasure by religion, and that have been perpetuated by early science, capitalism, and bureaucracy to instill morbid anxieties about illness, physical onslaught, decapitation, rape, unwanted pregnancy, abortion, miscarriage, gender restrictions, random annihilation--in short, all assaults on the body. The second bipolarization is the more specific myth that Ripley steers close to as she is represented in the model of the near-divinity or fair maiden (Astarte, Leto, Andromeda) who at one time would require saving by the splendid male god or hero (Baal, Apollo, Perseus) from the terrifying jaws of the serpent/dragon (Yamm, Python), but now saves not only herself but others, including men who are either reduced to heroic impotency or die in the effort to remain heroic.

The creators of the new Wonder Woman could learn much from Ripley's character arc, as they could from a careful study of the way the Alien directors made current mythopoetics out of classical mythology. Say, in the manner in which Cameron in particular shapes Ripley's characterization from the remnants of historical world myth, male and female alike--invoking variously Demeter, Orpheus, and Herakles from the Greek; Isis from the Egyptian with roots stretching to the African Wanjiru; the Mesopotamian Inanna; the Japanese Izanagi; the Blackfoot Kutoyis--all of whom descend to the dark underworlds of their dead in an attempt to rescue some beloved victim of a devouring power. When Cameron films Ripley in Aliens descending to the burning sub-basement of the refinery she is about to nuke (a techno-positivist equivalent of Hades that psychoanalysts since Freud relish comparing to the descent to the unconscious), she finds she is to save the little girl Newt (who is mythically identifiable with Persephone, Euridice, Dumuzi, Tammuz, Izanami). But suddenly the mythic pattern switches to that operating in Beowulf, Kuan Yin, St. Margaret, St. George, and Dargis, as Ripley becomes the destroyer of monsters and protectress of humanity.

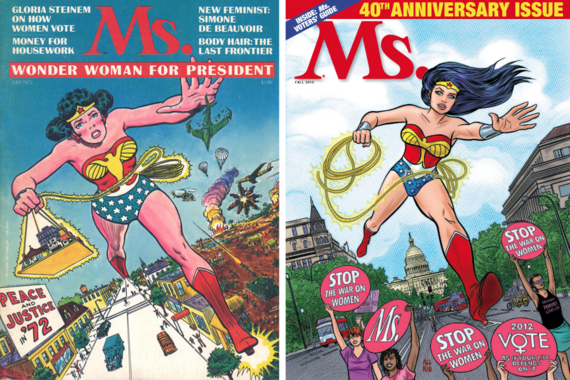

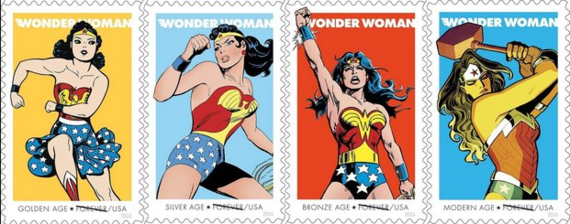

The Alien series' elevation of a woman superhero in film compels us to ask if DC Comic's relatively late media updating of the Wonder Woman mythopoetic is substantial enough to revitalize her feminist contribution to real political events in the culture at this late date. If we take the cue of Ms. Magazine's imprinting Wonder Woman on their October 2016, 40th-Anniversary cover -- a move that reiterates Gloria Steihem's initial confidence in the Mighty Amazon's symbolic power to rally women with the magazine's inauguration cover in 1976 -- then Wonder Woman at least for feminists remains unsurpassed as an ideological icon. But even the US Postal System issued Wonder Woman as set of four Forever Stamps depicting renderings of her in styles representing the comic industry's Golden Age (1940s-50s), Silver Age (1960s-70s), Bronze Age (1980s-90s) and Modern Age.

Perhaps the honor that may prove to have the widest global consequences is the naming of Wonder Woman as The United Nations's Honorary Ambassador for the Empowerment of Women and Girls, despite that several dissenters both inside and outside the world organization protested that "the honor should go to a real and less sexualized woman". But even the controversy surrounding Wonder Woman's fictional status bodes well for a very real presidential candidate supported by the women who grew up with Wonder Woman as a role model. It is the messiah story come true, however tarnished by the reality of myriad scandals and rumors. And so far, the recently released Wonder Woman movie trailer proves that Princess Diana will be as magnificently bestowed with mythological and mythopoetic grandeur as such recent male movie superheroes as Thor, Superman and the Dark Knight. How could Hillary Clinton suffer from association with such icons, especially among the male population.

The question remains whether the fans who grew up to be gender-politicized by Wonder Woman's mythopoetic development can repeat the political victory that for Barack Obama came in part by youthful fans of such early black superheroes as Black Panther, Storm, Cyborg and Green Lantern John Stewart. Although no studies have yet been conducted to correlate the development of political acumen and a penchant for social activism to an early acquaintance with the humanist ethics that inform the more noble superhero genres, myriad attendees of Comicons around the US share a sense of political duty when it comes to electing heroes for public office. The young people who helped to elect Barack Obama as our nation's first black President are were the generational recipients of a surge in African and African-American superheroes. This might seem a stretch of the imagination, but popular culture is all about stretches of the imagination, both in terms of what entertainment, art and fashion we digest and generate. And today the Presidency of the United States and especially its election cycle is becoming more and more a product and a production of popular culture. If we've learned nothing else from Donald Trump, surely it is that.

But cover of Ms. Magazine or not, we know that feminists since the 1970s professed a love for Wonder Woman that can't be matched by any one group of male political activists, except perhaps those inspired by Superman -- though even that affinity is not as overt or as resilient as the bond that women of the baby boom generation and after profess to have with Wonder Woman as their first feminist champion. It will be a unique claim to Clinton's supporters that her presidency conferred on November 8, 2016 came by way of millions of early acquaintances with an Amazon princess who wore a starred tiara and handled a golden lasso better than any cowboy could.

Will the Wonder Woman effect help propel Hillary Clinton to the most powerful office in the world? Whoever said that the narrative cliffhanger is dead was dead wrong.

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.