This is a review of the sculptural installation DJED by artist Matthew Barney at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery at 530 West 21st Street, New York, which will be on view through October 22, 2011. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10am - 6pm. To read about the Detroit performance and filming of Mathew Barney's opera Khu, on the sites of the declining auto industry, Detroit's Motown Review of Art by local Vince Carducci is likely the best-informed source on the web.

Art has both been proclaimed and accused of many dubious feats in the last century and a half. Now resurrecting the dead counts among them. The dead thing in reference is a car--though not just any car. It's a 1967 Chrysler Imperial, an Automobile among automobiles in a nation where the car was not only invented but mythopoetically imbued with powers beyond all prior expectations for an object. The thought that such an esteemed symbol of American exceptionalism requires resurrecting (When did it die?) may not be so outlandish considering that it issues from an American Empire where commodity is king and the car has come near to being deified.

The scenario comes into sharper focus once we realize it is written by Matthew Barney, our American Richard Wagner. Or really the parody of Richard Wagner. Barney's cycles of videos, films, and collaborative operas follow the Wagnerian model of presenting an audience a fully immersive sensory and dramatic experience--a total art work, or Gesamtkunstwerk to use Wagner's term. Both artists are also known for their singular redefinition of the art of their time by an extensive use of mythology--the reprisal of past myths--and, more importantly, mythopoetics--the innovation of new myths reflective of today.

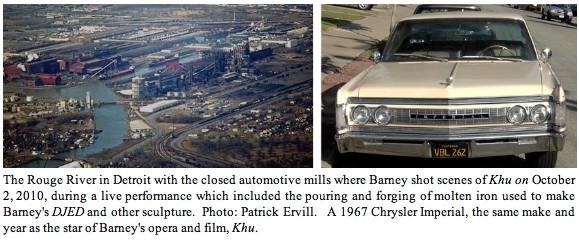

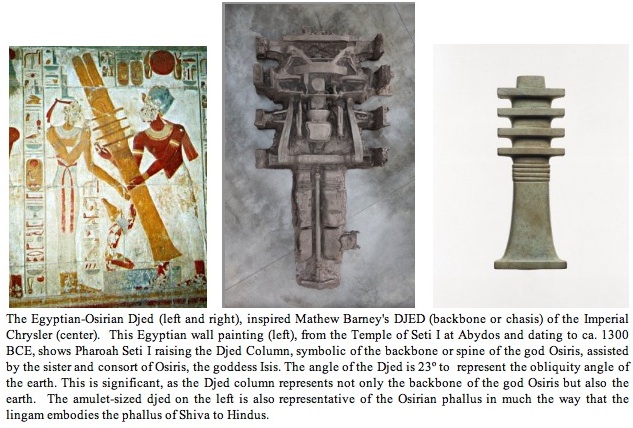

The analogy between the two artists has never been more relevant. Barney's latest epic, Khu, an opera made in collaboration with the composer Jonathan Bepler, attests Barney has never before relied on ancient mythology more. From his live and mobile outdoor performance of the opera in Detroit on October, 2, 2010--which also doubled as the shoot for substantial portions of his film--we know that the opera's libretto is a retelling of the ancient Egyptian passion play of the god Osiris, whose death and resurrection, many scholars believe, was a prototype for the organization of the Jesus story.

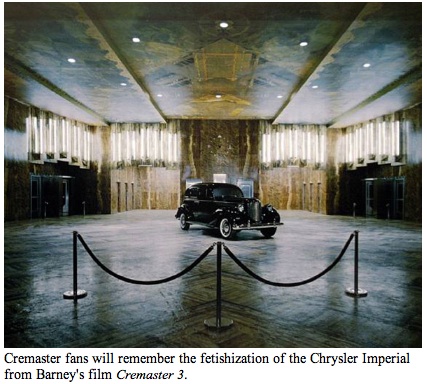

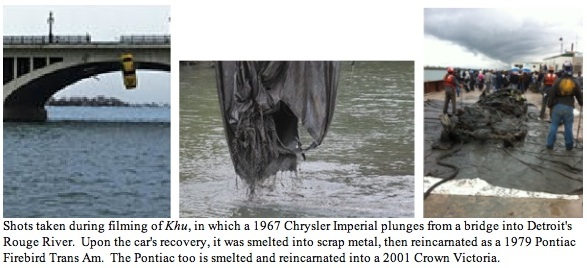

Yet the mythopoetic content is as significant, in that we find our dying god and central character embodied as a 1967 Chrysler Imperial. Artistically he descends from a much earlier vintage Chrysler Imperial appearing in Barney's Cremaster 3. In Khu, after plunging off a bridge into Detroit's Rouge River, the Imperial is dredged up, smelted down into scrap metal at an abandoned Ford mill, then reincarnated as a 1979 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am. If that weren't enough, the Trans Am is later reincarnated into a 2001 Crown Victoria.

If all this sounds like a Disney talking car film, think again. If we are treated to anything remotely like Barney's past films and performances, we can expect the kind of subversive imagery that comes with the modeling of multiple alternative sexualities, polygendering, competitive and dangerous sadomasochistic game-like power plays. And perhaps most importantly from a sculptural perspective, the extreme fetishistic relations between humans (or human-animal conflations) with inanimate objects.

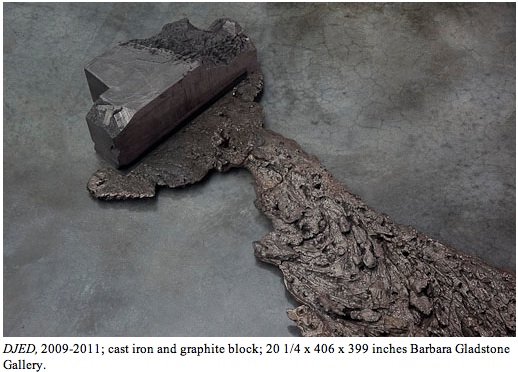

It's that last object/sculptural motif that is important to Barney's current show DJED, at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. Barney's sculptures, though exhibited apart from the total art work, are as much the product of his performances and recorded works as they are instrumental to the telling of a story--or some shadow narrative resembling a story. A better name for these objects may be "sculptural effects," as they, besides being integral to the plot and action as full-fledged characters, are materially born during the performances and film shoots--which is why I favor calling them "sculptural effects."

In the past, Barney's sculptural effects have on the whole been far less spectacularly received as sculpture in the gallery space than as characters in the performances and films. They also show significantly less facility for articulating the social equations and relations on which Barney and his fans fixate. Some of his sculptures even seem to suffer punishment for daring to stand apart from the total art work.

That's all changed with DJED, the sculpture from Khu. It's a cycle so successful as both independent and interrelated sculpture that the work even holds up to the old formalist test, by which the work must be proven meritorious as sculpture independent of its function as a vehicle of some exterior meaning. A sculpture succeeds the formalist test if it communicates with the viewer uninformed of the artist's intent. If this viewer can't read the work after adequate exposure, it can't be regarded as sculpture alone. It's more accurately a conceptual or theatrical object requiring access to external content and context for the object to be fully appreciated.

It's not the sort of standard that Barney's sculptures are known for meeting, given that Barney's total art work is the culmination of the maximalist extreme at the opposite end of the pendulum swing from the minimalist standard. And yet the DJED sculptures communicate as effectively as minimalist tautologies as they do as maximalist mythopoetics. Never before has Barney's work kept this teeter totter of aesthetic ideologies so balanced and poised. It's evident from the moment we walk into the Barbara Gladstone Gallery that the work possesses a gravitas and substantive materiality not seen in sculpture since the heyday of the Postminimalists and Arte Povera artists of the 1970s.

It's this yin-yang cycle repeating itself to the point that we can't commit to one school of thought or the other that reminds me of the void in our critical reception of sculpture. Sculpture as a medium has never been properly given over to a system for interpreting meanings outside its formal components. In its absence, we critics and viewers hoist onto content-laden sculpture like Barney's the kind of semiotics developed in the study of pictures. Or perhaps something akin to the hermeneutic approach used to decipher arcanely symbolic texts; or the lessons of cultural studies which help us to identify and assess far-cultural iconography and mythography.

But while these methods and systems are adeptly applied to the media they were derived from, they aren't adequate to identifying or analyzing the vocabulary of sculpture, particularly that sculpture imbued with the maximalist language that Barney's sculptures speak. This is largely the result of sculpture having been held captive to the reductive, formalist, and conceptualist turn of mind that dominated the contemporary sculpture and installation art of America and Europe for the better part of the Modernist Century.

It's not as if there haven't been contemporary artists before Barney investing their work with mythology (the reprisal of past myths) or mythopoetics (the innovative making of new myths). But only feminists working with sculpture between the 1970s and 1990s held myth in high esteem, largely because that is the rare language of the past within which narratives of the ancient feminisms survive. Even the art of Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer generated steep resistance to their mythological turns, though this was given to the artists' perceived "Germanness," an identification that spurred analogies to the Third Reich's anchoring in ancient Germanic and Aryan myths.

Whatever it's failings, the formalist test of sculpture at least tells us why Barney's earlier sculptures don't captivated viewers to the extent that his films and performances do. Before DJED, the relationships among Barney's sculptural components didn't fully gel. As observers in the world, we learn how things relate to us by comparing the way those things relate to other things--animate or inanimate. It's this history of observing relations that facilitates our emotional response to objects and ultimately allows us to recognize the sculpture's success or failure at providing us anchorage for meaning.

Sculpture that is indifferent to the human experience is absurd, which means it is resistant to our will to making it meaningful--as is much of Barney's earlier sculpture. It is largely the association of the sculpture to Barney's performances and films that give his sculptures the buoyancy of meaning required to keep them from sinking into obscurity. Of course plastics like cast polycarprolactone, thermoplastic, and self-lubricating plastic, by their facility for organic cellular suffocation, repel us while effecting disorientation. Of course, disorientation and repulsion are features of Barney's videos and films as well. But whereas his videos and films also supply the vital tropes we need to draw us back in, even if only to then disorient and repel us back out, we at least experience the breathing rhythm, the give and take, of two-way communication, something Barney's pre-DJED sculptures neglect.

By contrast, the DJED sculptures do facilitate significant communication on a variety of levels. They command conversation, whereas Barney's early sculptures flounder in their inarticulate existence. The textured and uniformly monochromatic black and silver graphite surfaces in DJED encourage iconic associations with, and fetishization of, industrial production. But they also give way to postindustrial nostalgia and anxiety. Like the best sculpture, they answer our need to mitigate the existential anxiety inflicted with the injuries of time by signifying some semblance of permanence--arguably the effect of Barney's first extensive use of bronze, iron, copper, and zinc.

Barney's mythopoetic investment in the DJED installation is heightened by what for him is its somber materiality and coloring; its powdery, chipped and unreflective textures; the blackness and greyness of the ash, dirt, detritus and slag deposited around the room. Some viewers I overheard saw the installation as a hellscape, an appropriate take considering that Osiris, like Orpheus, Herakles, Jesus, and numerous other world myths, must descend to hell before they enter paradise.

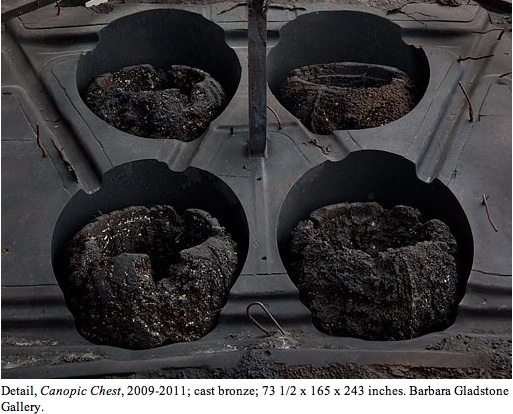

But for this operaphile, the sculptural assembly recall various sets I'd seen for Wagner's Nibelheim, the underground realm of the enslaved Nibelung forgers inhabiting the opera Das Rheingold. There is even a mound topped by a kind of forge of the Rhine gold--what Barney's calls his Canopic Chest. It's a primitive reminder of the blacksmiths who hold title to the roots of the forge of Detroit, just as it is analogous to the forge of Osiris, the god who takes on the form of a car in Barney's opera. Most relevant of all, the forge recalls the ancient analogy of god-creation to art making, the discreet equation that has long made gods a favorite topic of portrayal by artists who see such god potential in their own shaping of form into meaning.

In Barney's case the forge has "produced" a golden two-pronged smith's claw (Barney likely has a more elegiac name for it), with its gleaming, polished bronze-golden hue. Given that the Canopic jars of Egyptians hold the vital organs of the deceased should they be of use in the afterlife, the title seemingly endows the claw with the function of extracting the metal insides of the deceased Chrysler Imperial god. This is further reinforced by Barney's titling of his opera and film Khu--the name that the ancient Egyptians gave to the intellect, will, or soul that outlives the body and ascends to the stars.

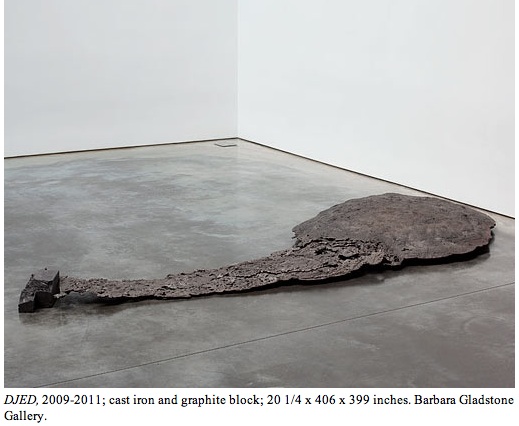

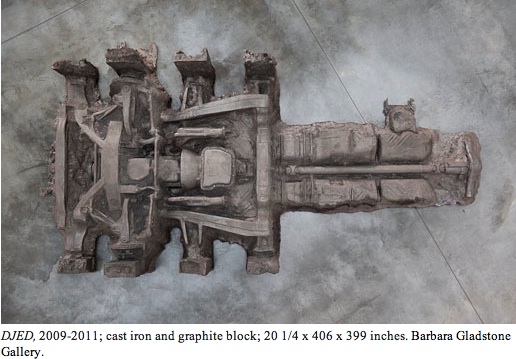

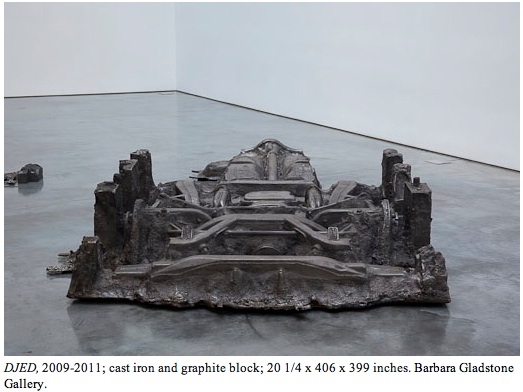

The masterpiece of the installation is the DJED sculpture, what we recognize immediately as a formidable, "fossilized" auto chassis resembling a dinosaur spinal column still embedded in the earth that betrayed its mystery. It's what remains of the Chrysler Imperial after it was dredged from the Rouge River and smelted down before a live audience during a performance of the opera Khu's third act. On the process of DJED's reincarnation, Barney's press release is vivid: "The primary form of DJED is the undercarriage of the Chrysler Imperial, modified to evoke the pillar-like hieroglyph of the Egyptian god Osiris' power. For this work, twenty-five tons of molten iron were poured from five custom-built furnaces into an open, molded pit in the earth at the site of a derelict steel mill along the Detroit River."

Even without knowledge of Barney's mythodrama, DJED and the sculptures surrounding it speak volumes about the decline of the American automotive industry and the shattering of the American dream for millions of workers. Except that the "fossil" that confronts us in DJED speaks not merely of decline, but of extinction.

Here is where the logic of Barney's choice of the Egyptian Book of the Dead as his narrative springboard is pivotal in a big way. This sculpture embodying the Egyptian myth of death and rebirth from a dynastic civilization 3,300 years in the past is the link from which we see our own contemporary civilization projected as far into the future. For as we think we are looking at the signage of some past civilization, we are startled to find we are looking at the signage of our own civilization as if through the eyes of those who will live thousands of years in the future.

According to Barney, each of the sculptures in DJED figuratively and literally embodies an equation between "transformations in a human body," with the "the recurring cycles of reincarnation ... creating a contemporary allegory of death and rebirth within the American industrial landscape." However premature Barney's operatic reflection on America proves, DJED is a sculpture that will one day manifest itself as great foresight. How could it not? The mythopoetic power of the car, aligned with the history of the open Road in America, was from the beginning destined to become one of America's, and Democracy's, most exalted myths. The automotive conquest of a continent, with all the empowering industrialization and economic prowess needed to eroticize and politicize the automobile and the road, remains the greatest collaboration between the poet-artist and the engineer.

We as viewers don't require full knowledge of the Osiris mysteries to appreciate that in Barney's DJED we're fathoming the inevitable entropy that marks our own future demise as a civilization. It's an anxiety that is always there at some layer of consciousness beneath our everyday distractions. It's informing American politics and media everyday. And although art is rarely taken seriously as warning, in its dredging up of our repressed fears--literally embodied in Barney's dredging the River Rouge for the once glorious Chrysler Imperial--it is for us each to find where we personally stand in this great scheme of unwinding time and space.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.