This is the fourth installment in the series, The 3D-Materialization of Art, an ongoing survey tracing the new and growing movement of highly-reflexive 3D spectacle and narrative art and activism. Made by artists who distance themselves from the commercial uses of 3D in motion pictures, television, advertising and gaming, the new 3D artists employ the same technology that the commercial industries use. The difference is the 3D-materialization artists extend the dematerializing values and strategies of Conceptual Art to digital imaging, narratives, mythopoetics, satires and paradigms that promote progressive and sustainable political, cultural and natural lifestyles for the present and future. The other Huffington Post features in the series include commentaries and criticisms on the 3D art of Claudia Hart, Kurt Hentschlaeger, Matthew Weinstein, Jonathan Monaghan and a related article includes the digital art of Morehshin Allahyari in a particularly global feminist context.

This particular installment, which previews the PostPictures exhibition at New York's bitforms gallery in Chelsea, and which opens on Thursday, December 19th, also explores the strategies by which the new imaging intersects with the larger range of new media art, including that found on the internet, in video streaming, social media, skyping, holography, and virtual domain art. Consult the bitforms website for more information.

PostPictures is the name of the exhibition assembled by curator Chris Romero and gallerist Steve Sacks at New York's bitforms gallery in Chelsea. The show's nomenclature may strike us as curious, even dubious. For what can come after pictures but more pictures? Of course, anyone not holed away in a cave for the past two decades surely has the answer on their lips. PostPictures is the revolution in new media, the internet, video streaming, gaming, social media, skyping, holography, digital animation, and virtual domain art.

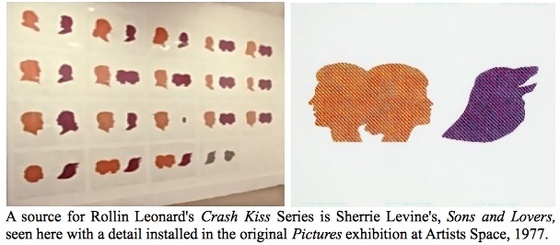

But the bitforms exhibition isn't concerned only with new imaging capacities and access. The 'Pictures' in 'PostPictures' also alludes to developments in response to the art historical Pictures Generation who came of age in the mid-1970s. In fact, the term 'Pictures Generation' was coined after a 1977 essay written by critic Douglas Crimp, which unified a small, informal sampling of the growing number of artists who nascently advanced a common concern for the revival of picture making--though not without ensuring that the pictures they made reflexively referred back to the acts and attributes of picture making itself.

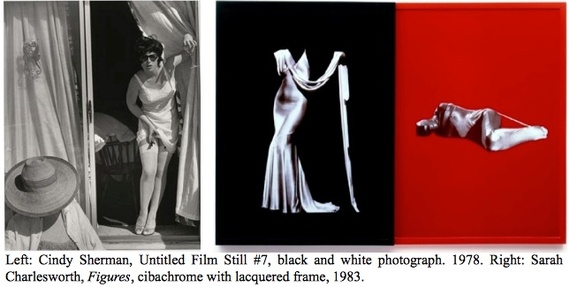

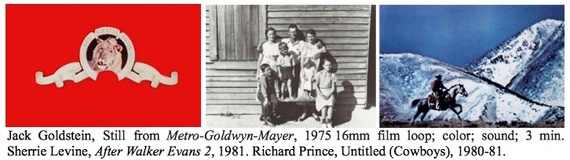

Crimp's essay accompanied an exhibition at Artists Space in New York, now remembered as the Pictures show, which represented his view that the artists' reflexive proclivity for making pictures about picture making, along with their heightened attention paid to the discreet cultural codification that pictures disseminate, reinforce and perpetuate, was seen by art audiences as a vital alternative to the formalist corner that the artworld had backed itself into by the late 1960s--a corner from which no view of passage for ideological or aesthetic egress could be seen. Within a year, the designations 'Pictures Generation' and 'Pictures Artists' came to identify a wide range of young artists, many not in the original show, with the most notable being Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, Robert Longo, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, Jack Goldstein, David Salle and Barbara Kruger.

To understand the Pictures Artists' obsession for reflexive picture making, we must first understand that the 1970s generation was both reacting to and retaining some measure of the Modernist proclivity for tautological endgames--the making of art reflecting its own mediating and cognitive processes which were deemed to be the furthest advances to which artists could take art. Abstract painters thought that two-dimensional, non-illusionistic abstraction was the furthest art could be taken. Minimalists, who claimed that two dimensional art was an illusion, thought that a sculpture of gestalt forms (forms we can summon to mind with little difficulty, such as cubes, cones, pyramids), were the reductionist end to which art could be taken. But it was when the Conceptual Artists of the 1960s and 1970s seemed to have taken art to its furthest limit in making the Idea itself the art, the artworld was bereft of any further facility to develop, leaving it facing the prospect of its own sterile demise.

In knowing these endgames and the severe limitations they imposed on artists only t00 well, the Pictures Artists saw no recourse but to ignore them. But because the art of the avant-garde had for a century limited itself to making reflexive art that acknowledged its own properties and processes, the Pictures Artists felt compelled to make pictures about picture making and the culture of picture making. For this reason, the Pictures Artists as a whole are thought by many commentators to be historically valued today largely for the portal they pried opened through the formidable wall of Modernist formalism. But it was a portal that was exceedingly narrow. Besides which, the Pictures Artists had not foreseen that by reintroducing pictures as a formal discourse in late twentieth-century art, they also made it easier for the subsequent generation of PostPictures artists to introduce an even more vital art of pictures that was unhindered by formalism.

Like the Pictures Artists, the emerging PostPictures artists refused to perpetuate the formalist endgames which had for decades closed off the artworld to artists who worked in pictorial modes. But they also chose not to limit themselves to making pictures about picture making. The pictorial art from the mid-1980s on was so protean, that it made the Pictures Artists appear severely stunted, to the point that none of the Pictures Generation, not even Cindy Sherman, seemed to grow beyond the high water mark of their mid-1980s inventions.

Although indebted to Pop Art's reflections of popular culture, Pictures Art is more minimal and less ambiguous than Pop Art. As a result, we often get what Pictures Art conveys in a first glance. When we encounter Jack Goldstein's looping film projections of images taken directly from cinema--say the classic Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion clipped from the opening of any one of their films in the 1960s and made to endlessly roar--we know that the Hollywood brand is being held up as a model of cinematic authority and quality, though perhaps not in the way that the studio intended it. When Sara Charlesworth rephotographs magazine cut-outs and floats them in monochrome fields, we recognize how the missing context of the picture is as important to its reading as the subject and the message. When Sherrie Levine rephotographs revered silverprints by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston and then audaciously attributes her own authorship to them, and when Richard Prince represents entire Marlborough ads as his own creation, we recognize that a shift in the ideas of authorship and copyright are being advanced as a statement about the shared cultural history of artists outweighing individual identity in the progression of civilization. And when we find Cindy Sherman mimicking mid-century screen divas in mock film stills, we recognize that Sherman is parodying how the most elementary pictures are invested with the cultural codes that tell us how to look and behave in given social circumstances.

Crimp saw that the Pictures Artists were opening outlets for a century of pent-up frustration among non-formalist artists yearning to revitalize an art of content since abstraction had first stolen away the international attention some seventy years before. In this regard, Pictures theory from the start was a hyper-theoretical offshoot of Pop Art, crossed with Minimalist Art, Conceptual Art and Performance Art--a hybrid that capitalized on all the semiotic afterthoughts about visual media that grew out of, and retroactively was used to articulate and critique, the advertising and media empires that Western art forms mirrored in the late 20th century. It helped that Pictures Art appeared just as critics were eager to put to use the semiotics theory being retrieved by academics from the decades-earlier publications of Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce, along with the more recent structuralism of Roland Barthes, the media analysis of Marshal McLuhan, and ultimately the Deconstruction theories of Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man--all grafted onto the politicized lectures of the Frankfurt School, particularly the critics Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse.

That much is the history informing PostPictures. But bitforms' PostPictures is also intended to remind us that the Pictures Generation impacted the artworld just prior to the popularization of vector-rendering software, such as Maya, Z-Brush, Mental Ray and Shake, which variously serve as the structural mesh of infinite digital modeling and pictorial design. Yet this near miss only further underscores to what degree the 'Post' in PostPictures points to a picture making about picture making that reflects its greatly enlarged capacity to picture the infinitely-protean virtual domain and its relationship to and affect of reality. In other words, to at last make picture making as protean and unbounded by limitations as dreaming. It is only a matter of a decade or two after the Pictures Generation that a generation of New Media Artists, armed with the digitally-enhanced technical capacity of emerging platforms, began to revitalize and redefine how pictures are made and what they are to mean for a generation who never knew the severe formalist and tautological restraints of the preceding century of avant-garde artists.

It is imperative to here point out that PostPictures is not being conceptualized by bitforms as a corollary- or counter-exhibition to the original Pictures exhibition associated with Crimp and the Pictures Generation it spawned. Neither is it intended as a survey of the new PostPictures Generation at work on digital platforms. The artists in this first PostPictures exhibition have been chosen with a measured restraint of ideological claims concerning the selection. By that I mean that PostPictures is no more than a preliminary representation of a model of digital picture making being advanced by New Media PostPictures artists who, like the Pictures Generation before them, distance themselves from the mainstream of pictorial and narrative digital productions--from cinema to gaming, journalism and advertising--while charting out a new paradigm beyond the history of digital art that has been concerned with the theories or the technics of the digital enhancement of media.

Finally, the term 'PostPictures' conveys not only the heightened pictorial domination over the cognitive infrastructure of communication in art, media and design, but as well the renewed emphasis on vision within the hypothetical sciences--to the extent that theoretical physics and genetics have arguably made the digital imaging of hypothetical models equivalent with, if not prior to, mathematical formulation in the generation and conceptualization of their paradigms of the physical universe and life forms. In this ideological, social and technocratic expanse, PostPictures artists take on the challenge of presenting alternatives to mass media and cultural institutions alike, and doing both by proposing new models through which art will operate as cultural documents presenting, apprehending, and construing the world in much the same way as religion, science, common sense, and political ideology formerly represented knowledge and world views.

The Artists of PostPictures

Claudia Hart

Claudia Hart's most recent evolution as a modeler of 3D pictures grew out of her desire to escape from the violent misogyny of gaming and other special effects media--a desire that literally and expediently grew into a series of utopian eScapes--meticulously-produced, 3D animation videos made with the same special effects software--Maya, Shake, Z-Brush, and Mental Ray--propelling Hollywood mega-studios DreamWorks and Pixar, and now the proliferating dream labs servicing the entertainment film industry around the world. Exhibited sometimes on conventional flat screens, they are also effectively projected onto whole walls so that viewers can experience their full pictorial impact. The enlarged scale also enables viewers to appreciate the work's embodiment of mythopoetic and structural models.

In their mythopoetic functions, Hart's eScapes are designed to afford women models for safe ideological havens sheltered from the adolescent hetero-male fantasies driving the entertainment, gaming, and advertising industries. Such an orientation reflects Hart's view that the mainstream productions have become a primary source for the formation of world views. Knowing that today's popular culture increasingly supersedes on the formation of world views once largely constructed by religion and science, Hart believes that the entertainment and gaming industries are producing more than warrior wet dream machines. Operating ritually and unconsciously in young minds on the level of belief-formation, video games and movies inform personal lifestyles, identities, and priorities profoundly affecting relationships and practical functioning in the world. When factoring in media imagery disparaging to women, misogyny becomes internalized not merely as a prejudice, but as a "desirable" fact of life for many young men.

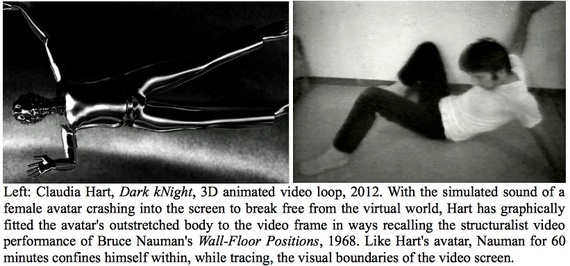

But in creating Dark kNight in 2012, Hart felt it was time to begin a migration out of the sanctuary cocoon of her earlier animated automatons to symbolically confront and counter misogyny. In her re-emergence, she chose an avatar to represent the attempt of a defiant automaton who not only seeks to escape one of her own eScapes, but to break free of the simulated sanctuary world behind the screen. As the title implies, the work is Hart's response to the popular Christopher Nolan blockbuster, Dark Knight Rises, a film about escape from imprisonment and the fascism that deems who is and isn't to be imprisoned. With the film's two highly independent, physically athletic and defiant female characters, both of whom have escaped their own entrapments, Hart was immediately prompted to envision her own restless, racially-hybrid female avatar trying out various strategies to escape virtuality. In the video we see Hart's Dark kNight hurling herself, feet first, into the screen in an attempt to smash through it. Hart claims the mythological source for the figure, besides Nolan's Batman, is the chained Prometheus, bound by the Olympian gods for bringing fire to humankind. Artistically she is inspired by Michaelangelo's Dying Captives, who appear to struggle in their efforts to release themselves from their prisons of stone.

In the space of it's installation, the sound of the automaton crashing against the screen embodies the artist's reflexive sounding out of the digital medium in the making of a virtual picture and its narrative. Visually reinforced by the frame of its flatscreen, Dark kNnight exemplifies PostPictures not just pictorially, but in its metronomic audio. No matter where we move throughout the space, we hear the pictorial figure "hitting the screen", so that the Dark kNight audio of the figure--or the picture itself--repetitively and rhythmically "hitting the screen" functions throughout the space as the metronome sounding out the futile attempt to escape picture making. The audio reflexively reinforces the pictorial experience and its potential longevity in a way that no other video audio has done since Joan Jonas' Vertical Roll, while visually Dark kNight recalls the 1970s analog videos by Bruce Nauman in which the artist maneuvers his body to snugly fit within and trace out the boundaries of the video monitor as the pictorial restraint it is.

Rollin Leonard

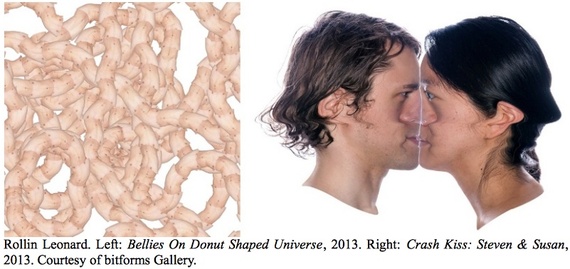

Rollin Leonard exhibits many tendencies that revitalize the pictorial strategies of the Surrealists, chief among which is the idea that our experience of the human body effects the way that we construct the world in our minds. Despite his work's rococco (that is, its stylized, robustly organic) exuberance, Leonard recalls the photographers Man Ray, Brassaï, and Hans Bellmer, along with certain of Dali's figurative paintings, in the manner that he favors a severe cropping of the body, compounded with a repeated doubling of that cropping. In certain works, Leonard appears to see in the body a model for effecting an infinitely protean replication--an organic structure growing itself without limit in hive-like cellular replication, yet with the relentless uniformity and exponential pictorial reproduction of a printing press.

Leonard's replication and cropping are only matched by his overall dissolution of the body, what occurs when body parts are so uniformly and numerously cut and pasted that they become abstractly-patterned, even ornamental strategies. Such an ambiguous and mechanized reduction of the body to a potentially infinite facsimile frees the artist from the cliches of the fetishistic associations that had restrained the body condensations of the Surrealists.

The suggestion of rampant replication in Bellies On Donut Shaped Universe (2013), is the means by which Leonard purposefully denigrates the capacity of his picture's facility for visual cliche at the same time that all eroticism is drained from the composition by drowning any semblance of individuality in a sea of stamped-out, undulating and purposefully monotonous male torsos surrendering to the matrix of homogenization. Leonard's replication is so relentless, it recalls the metaphysical principle that the mind's faculty for difference is nowhere more threatened than by its absorption within an absurd universe of infinitely suffocating sameness. But a counter view also competes throughout his work, in that the trace-like motion of Leonard's embodiments recall the infinite mirroring of the human form that have been treated with the unbridled creative desire of a protean urge reminiscent of the flowering archetypes of Hindu, Tantric, and Tibetan Buddhist figurative art. In evoking ancient divine-yet-monstrous unfoldings of voluptuous and voracious deities and demiurges growing potentially unlimited appendages, Leonard comes full circle to evoke ancient elaborate symbiologies of love and war joined with the unbounded variety of contemproary permutations generated and propelled by algorithmic formulas.

In a less profuse vein of pictorial composition, Leonard's portrait pictures are given over to the conflation of genders, identities and roles--in short, a canceling out of difference and a rupturing of continuity, presented as a casualty inflicted on portraiture. The breakdown of the portrait is a departure from the more coherent modeling and building up of the virtual domain that most virtual artists favor. Leonard's Crash Kiss: Steven & Susan (2013), which photographically represents an assumed couple voided of key features of identity, mashes all criteria for what constitutes the individual and the shared. The effect is to leave us feeling that Leonard's vision encompasses a process that shows no patience for the old pace of gradually eroding away at the threshold between waking and sleeping that Walter Benjamin romanticized. For in whatever boundary Leonard does not replicate, he makes recourse to dissolve.

Sara Ludy

Sara Ludy invokes our individual and collective histories of media navigation within video streams comprised of elegant interiors. But depictions of space aren't Ludy's only concern, as our witness of prolonged dissolves from one picture to the next point us to an ongoing segue of time in the passage between pictures of interior space. By according the dissolve with care equal to that shown the composition of spaces in pictures, Ludy recalls our every experience of the image stream, from home slideshows to global newscasts. Besides redefining our experience of pictures to include time as a feature equal to space, the segue reminds us that even the still picture in the virtual stream is in constant transition, and thereby is as subject to the physical laws of space-time as a dimensional continuum of the mind. This handing over of the still image to the indiscriminations of time may not be unique to PostPictures, but Ludy works to free the photograph--or more accurately, the simulated photograph in Ludy's case--from the sentimentalism that encumbered photography since the mid-19th century, when William Henry Fox Talbot praised the nascent invention of paper as the medium best suited to facilitate photography as a means of documenting even the imperceptible "injuries of time and weather, in the abraded state of the stone".

The choice of collecting stills of interiors is as formalistic in their mundane schema as an architectural seminar. In fact, the stream of spatial images replete with dissolves give her work a documentary air--but an air that is wholly illusionistic given that the greater number of images are culled during Ludy's daily visits to a succession of 3D habitation models in the popular 3D game grid of avatar play known as Second Life. On the other hand, the aestheticism of the ellipses that usher our eyes' passage from one pictorial boundary to the next, and with little if any variation in speed, endow Ludy's pictures with a hypnotically stark, Zen-like aura reminiscent of breathing and blinking. But as if to show us that her immersion into virtuality is to trump more conventional metaphors of space-time, Ludy pointedly informs us that her repeated immersions into virtuality leave her experiencing the same syndrome that non-stop video gamers suffer after days of gaming--a debilitation of the way one's surroundings are perceived, what she calls "a virtual spillover into reality" that she seeks to project into the space for the random visitor to encounter and perhaps recognize.

Ludy's acknowledgement of the Virtual Withdrawal Syndrome alerts us to a very real-world concern. Like the Gamer Syndrome, there is a Pictures Syndrome of being unable to distinguish real spatial and temporal features from the virtual picturing of space and time in domains such as Second Life. But on close inspection, the similarities between the mind and the virtual domain suggest that the pictures syndrome is not so much an affliction as it is an alert recognition that pictures are a kind of real experience of the world in much the same way that our mental picturing of the world in memory is. In other words, the pictures of reality we call the ideas of the mind are, in fact, what determine the nature of our experiences of space-time in the world. In this assertion, Ludy implies what mystics and phenomenologists alike have been telling us for centuries--that the space and time we believe is in the world is actually part of a pictorial construct in the mind. In fact, that reality in its entirety is a picture in the mind.

The difference that comes with digital picturing, Ludy implies, is that in the real world we can't show that any two people, let alone all people, share the same reality of space and time. For both the world and the mind are outside our creation and definition. However, because the virtual domain is humanly designed and mediated, we can show that within the virtual domain, any two people, and possibly all people, do share the same reality of space and time--even if we don't experience it in the same way. For though our sharing cannot be termed wholly "objective", "certain", or "precise", the on-demand demonstrability of a virtual grid comprised of polygons and vectors in the computer can be pointed to as our objectively-shared source for infinite picturing. It is this virtual grid--say the grid of Second Life that Ludy comes back to day after day--that compels us to adopt a new faith in shared subjectivity. This is what PostPicturing means: that we can demonstrate that we share a subjective response--an intersubjectivity--to a pictorial stimulus that can be pointed to with an assurance that that picture exists in two or more minds, even if perceived differently in each.

Shane Mecklenburger

With the media, entertainment and gaming industries shaping the world views of millions of its users, it is inevitable that big media pictures shape the way that different kinds of people respond to high-issue objects such as guns and rare gems. Shane Mecklenburger takes a philosophically detached view of what he believes is "the inescapable connection between science, technology, war, art, wealth and violence". As both media and virtual pictures play a key role in this exchange of values, it seems only right that Mecklenburger looks to the simulation techniques of 3D videos and New Media sculptural installations to externalize his thoughts about the modern fixation with guns and high-end commodities.

Mecklenburger has converted the strategies conventional to such pictorial narrational industries as film, video, gaming, advertising and the internet to craft a performative sculpture and video art poised for making inferential leaps leading from the behavior of youth at video arcades and home game stations to behavior at the diamond mine, the airport import counter, and the precious gems galleries of the world's major metropolitan centers. The work is more subtle than we might expect. Instead of mimicking shooter games and combat simulators for their viscerally addictive virtual rampage slaughter of opponents from the comfort of one's chair, Mecklenburger prefers pictures that indict the more discreet, but greater commodity lusts that extend from oligarchical politics in capitalist societies and works its odious imperatives down the class ladder to the street arcade.

It's a subtle chain of associations, and it is summoned to mind in Mecklenburger's work by the dialectic between two objects: a simulated gun--in the bitforms exhibition mounted in mimicry of the arcade or home gamestation--and a video of a dreamlike diamond vein in continual flux which periodically becomes flushed with a magenta stream that can be easily, if ambiguously, associated with blood. The off-color liquid keeps us guessing rather than hammer Mecklenburger's point. He could as well be indulging his aesthetic and technical reflexes at what they are so good at--the crafting of virtual pictures that are as lushly aesthetic as they are evocative of the social dynamics that make up world economies. The added factor in the bitforms exhibition of refashioning the conventionally-masculine video game as an elegantly feminine vanity table, with its mirror magically become a flatscreen and its fragrance bottles converted into a control station replete with a crystalline gaming gun, funnels further baroque complexity into our experience of the screen as a fantasy reflection of our own narcissistic desires. The basement boy game taken to manhood in the bedroom connotes the compound layering of adult, sexually-charged fantasies of prowess grown over a history of adolescent gaming syndrome come to informing adult images of virile conquests facilitated by the acquisition of courtship commodities.

Why is the diamond rendered as a picture and the gun as a sculpture? This is where Mecklenburger's cultural insights join admirably with both his heightened media instinct and his facility for logic. As guns aren't usually ends in themselves, but rather means to an end, they thereby aren't as likely a primary picture of desire in the mind to the degree that the essentials of life are--a delicious meal, stimulating sex on demand, set-for-life wealth. And though diamonds are an object to be ostentatiously paraded in public, the far more utilitarian and compelling object required to impose one human will over others--and thereby the more suitable for sculpture--is the gun. The beneficiary of this ingenious pictorial and spatial dialectic of archetypes and logic, is the gallery viewer who is invited to game the gallery in any number of avatar images from diamond miner, mercenary smuggler, gem collector, politician on the take, even--given the work's subtitle, Fortress of Solitude--the ultimate childhood idol object of the superman who can crush coal into diamonds with his bear hands. (The title, we are told, also refers to Mike Kelley's Exploded Fortress of Solitude, which Mecklenburger claims impacted him powerfully, as did the artist's suicide last year.) "Hidden within the vanity table control center, is my own version of Kandor--the miniaturized capital city of Krypton in a bell jar--also a favorite subject of Kelley's." In the end, it's not logic or reality that Mecklenburger points us to, but the mainstream media imagery that insulate and arrest largely male, but increasingly female, development with pictorial reinforcements extending adolescent fantasy into adulthood, rather than confront such fantasies with the reality of growth.

Jonathan Monaghan

Jonathan Monaghan comes to picture making with one eye acutely set on advertising and the other on blockbuster cinema, twin industries that have become the launch pads for the mainstream virtual animation and special effects industries that have radically reconfigured the world views of billions of the world's youthful viewers and the mythopoetic narratives that fuel them with ideological fodder. In Mothership (2013), Monaghan acknowledges his debts to the Pop Artists of the 1960s and the Pictures Artists of the 1970s, through his free use of commercial logos Googled and then commingled into one unique, yet distinctly hybrid, pictorial brand intent literally, stylistically and figuratively for global domination.

Monaghan lightens the tragedy of our global conglomeration by underscoring it with the self-deprecating humor we postmoderns typically reach for when faced with the despair we feel in the shadow of corporate monoliths. Aping the paternal "benevolence" that networks broadcast and internet sites stream to placate their ten billion children, Monaghan placates us with pictures in the fashion that we, the first TV generations, were placated with as infants by the astonishing moving pictures and sounds that our eager parents, grateful for the entry into their home of a network of authority and wizardry, subjected us to in the form of the first cathode rays of indoctrination.

It is our unconscious, infantile delight that Monaghan taps and jiggles the lure for--in this case pictures that, in Spielberg-like fashion, appear intent on ideological persuasion, if not invasive mind control, undercut with a Pixar-like (read infantile) seduction-by-animation. Taking on what is commercially engineered by an entire effects team bent on sweetening our submission, Monaghan ironically effects our silence while drawing our attention to it.

As the Mothership descends, viewers will be amused by the incongruent decoration of the aircraft with the inane imagery of their childhood--specifically the descending black and white cow. (Black and white, we are told by animal evolutionists, are the colors that wild animals evolve as they become increasingly domesticated and docile with each generation). Like a dream foretold by Disney, a vision of our liberation majestically descends as the presumably benevolent, yet no less ominous, corporate supership tranquilly confers narcotic bliss upon us--a bliss which softens the sight of the slick metallic shell emblazoned with the signage of some inbred child of American Airlines, American Apparel and Fed Ex. The ingenious ambient soundtrack by Evan Samek closes the sale in the fashion that we can expect from only the most sophisticated and slick advertising--composed to support pictures that ensure we are as captivated as we are captive. In this, Monaghan delivers his product as if we are some mesmerized, isolated island tribe gratefully receiving the descent of wishfully benevolent gods.

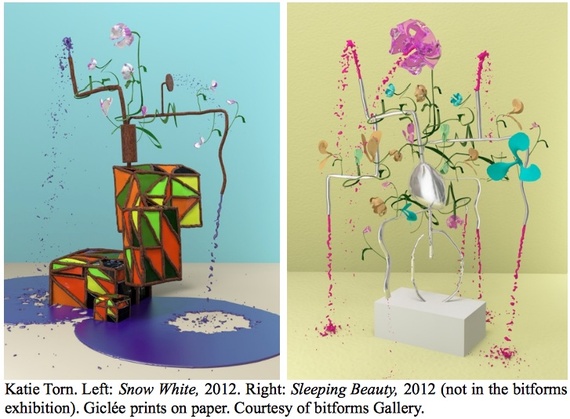

Katie Torn

Katie Torn's digital prints are the rare 3D forays into the processes of a pictorial abstraction more conventionally pursed by painters than by virtual modelers. Inspired by Cubism and Futurism, they also embrace the world's tribal arts that significantly impacted on Modernist picture making in the first decades of the 20th century, particularly with their borrowing of totemic and fetishistic sculptural traditions found among the indigenous populations of the Neolithic world. But Torn finds new life in these bygone and indigenous schools to the extent that she suggests that modeling avatars can be transported forward to new virtualities by first traveling back to the still-vital productions of Cubist, Futurist and the world's tribal artists.

Structurally, Torn's videos assimilate aspects of animation, painting, sculpture, cinematography, and audio art. Conceptually, they evoke fantasy worlds that mix metaphors and media to disrupt our expectations of what fantasies should look like. Her inkjet prints are a case in point for making such fairy tale heroines as Snow White appear as if rendered by a conflation of Modernist artists as varied as Leger, Mondrian and Klee. The strategy is a beguiling subterfuge. We may think we are looking at an appropiated painting, when in fact we are looking at an authentic Torn inkjet print. It's no small accomplishment that Torn's translation of painted schemes into pixel hues is faithful to the art historical movements she recalls. And because they depict a single, fixed pictorial picture, not a succession of scenes in video or film, we don't recognize that they are in fact the product of animation software modeled with a computer. But then Torn takes the same approach in her videos--reducing motion to near stillness and small gestures, rather than the dynamism for which her software was designed. Defying the animation genre, Torn glamorizes stillness with motion-picture technology, her way of dismissing the ostentatious cinematic and gaming videos that the commercial 3D industries have distributed around the world. As most of her recent works are comprised entirely of 3D-modeled and -painted figure-and-field relationships, they are best described as models of 3D painting, or simulated painting paying homage to the crafts of painting and print making she admires.

It may seem a perverse use of elaborate and expensive software algorithms to model what can be more easily made with cheap brushes and paint, or as well with lithography. But Torn's recourse to 3D graphics persuades us that the figurative modeling usually employed to craft avatars and their mapped environments is a logical and effective continuation of the same visual aptitude for line, shading and light in the building up of illusionistic volumes, contours, surface colors and textures from pixels, as that required for the modeling of figures and application of layered hues on a canvas. Torn's art, for that matter, seems to be elaborated as an argument that the mastery of computer imaging is dependent on the same artistic hand-eye/eye-brain coordination that our ancestors developed in making cave paintings.

Torn is one of the new generation of 3D artists who signals to us that at least the artistic enclaves using cgi are slowly shifting the prejudice of cgi away from its Hollywood applications in crafting photographic illusions to the revised use of painting realized entirely through the techniques of computer simulation. Whether or not this means that cgi will become the dominant mode of future painting is to be contended. But Torn's 3D video and prints suggest that were Picasso, Matisse, Balla and Boccioni alive today, cgi would be their medium of choice.

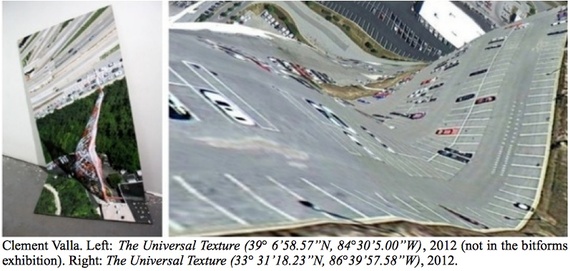

Clement Valla

Clement Valla has not made, but discovered, a true PostPicture in the field. At the root of his process, Valla collects Google Earth images, or what 3D artists call texture mapping, and converts them into pictures that grow into sculptural spaces. Hugging the wall conventionally, they turn to sprawl across the floor or extend into the viewer's body- and eye-space. But such conflations of pictorial and sculptural dimensions have been renowned throughout the history of Modernism. What truly sets Valla apart is his choice to display not just a Google texture map, but a picture in which the classical, illusory perspective of a seamless surface of the Earth, in Valla's words, "seems to break down" within the picture itself. Valla in fact discovered that this "break down" in Google Earth aerial photography is not the result of glitches in the picturing technology, but are located in the illusion we customarily summon to mind of the Earth being covered by one continuous surface. In reality, the earth that we see in Valla's recycled pictures are marked by what the artist calls "an edge condition"--"an anomaly within the system [of picturing], a nonstandard, an outlier, even, but not an error."

Valla informs us, "These jarring moments expose how Google Earth works, focusing our attention on the software. They are seams which reveal a new model of seeing and of representing our world-as dynamic, ever-changing data from a myriad of different sources-endlessly combined, constantly updated, creating a seamless illusion." (All citations are from Valla's statements on rhizome.org.) Upon looking at Valla's aerial Google scans, we can quickly locate these seams. We find them where buildings that contiually appear to face eastward butt up against buildings that suddenly face westward, indicating that a second camera had scanned from the opposite direction, with an entirely different point of perspective departure. Similarly, a deep examination of the maps's shadows correct our cursory-yet-false impression that a city model has been lit from multiple light sources, when, in fact, the photo is a composite of numerous discrete photos indicating the passage of time--that is, the multiple locations of the sun's motion in a given day, week, month, even year. In fact, what we see in Valla's work is a PostPicture descendant of Modernist collage, though it is a collage that follows a rigorously programmed and mechanized scheme in space-time, despite that the visual effects of the scheme appear to be disjunct, and the deduction we make logically from the picture, when not taking into account the program for the photographic venture, wrongly produces our assumptions of a project in periodic disarray.

Valla's art can be said to evidence the very ratio between human perception and cognition to the world at large in terms of exhibiting a limited system meeting up with a boundless and potentially infinite system. The resulting equation, as Valla's pictures display, indicate a disproportion that relativists have long claimed about the picture we carry of the world in our minds. That is, that our minds are too small to picture the vast and contradictory differentiations of the world. Or as the British mathematician and logician, Alfred North Whitehead, put it, human attempts to understand phenomena extending beyond human experience invariably produces "a fallacy of composition"--what confounds human minds when trying to insensibly picture things significantly, even infinitely, larger than the the mind that attempts to contain it.

It seems that Valla, following Google's lead, welcomes Whitehead's skeptical challenge when he points out that 3D imaging has advanced our capacity for seemingly endless (if not infinite) mapping through the invention of the so-called Universal Texture. As Valla explains it, "The Universal Texture is a Google patent for mapping textures onto a 3D model of the entire globe. As its name implies, the Universal Texture promises a god-like (or drone-like) uninterrupted navigation of our planet--not a tiled series of discrete maps, but a flowing and fluid experience." It isn't the first time that a pictorial system was afforded the attribute of omniscience, and this PostPictures attempt at constructing a Post God-like view isn't likely to be the last.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.