When considering torture and terror, the first question of relevance is, Do we require an experience of torture and terror first hand, either as a survivor or as a witness, to be credible on the subject? In our humanity, as much as in our vanity, we may defensively insist that our recognition of the immorality of torture requires no more than the empathy fundamental to distinguishing what is humane and what isn't.

Generally, humaneness by itself suffices for the maintenance of a civil society. It may even be adequate for compiling our histories and mythologies of civilizations. But empathy born in the fortunate inexperience of severe and widely practiced cruelties of war and authoritarian regimes cannot supply insight on the dark spaces of the psyche that open up to the individual desperately fleeing the injuries and trauma inflicted with a tyrannical and sadistic force. Which is why I choose to argue that a civilization that is by and large blind to such atrocities as torture and terror require an art depicting such atrocities to keep us properly outraged by their obscure persistence.

This question of experience is especially peremptory when torture and terror are to be made the subjects of the mimetic arts--those pictures, dramatizations, and narrative accounts that signify, embody, and analogize human experience. Unlike histories or mythologies which depend respectively on facts and social conventions handed down to us by prior generations many times removed, in the arts we tend to remain prejudiced in favor of the first-hand experience that informs an artist's picture making and storytelling. And when it comes to depictions and accounts of torture and terror in particular, some voice within us insists that we cannot derive the full force and shock of traumatization from secondary sources.

We all recognize the overtly authoritarian efforts to terrorize populations from having been steeped in their imagery from an early age in our news reports and entertainments. But our most powerful and shocking acquaintances can be incurred from survivors whose direct experience of torture and terror have been callused over by years of recovery. They alone present us the nuanced signage instructing us, however silently, that theirs is a voice or a vision formed by the direct experience of torture or terror. Whether encountering survivors in person, reading their accounts, or viewing their art, it may be that the compelling first signs of their experience is conveyed by the slightest evidence of a compulsive behavior--a twitch of the body, a hesitation or an avoidance of the most common thing or circumstance. Although slight, from such signs we learn and read what traits survivors retain from the traumas we lack.

In art, the proper mimicry of these nuanced signs of trauma, and especially the isolation and framing of these signs by the appropriate political and moral context and presentation, makes trauma readable to anyone possessed of the most rudimentary recognition of healthy behaviors. Such subtle readings are generally absent from secondary sources and inexperienced artists. Which is why audiences for the arts often favor, even insist on, the artist who can recreate from personal memory what it means to be imprisoned, tortured, terrorized experientially--through his or her own pain and terror--whether personally suffered and survived or directly witnessed.

Then too, as we dig down beneath the surface of our democracies, we find that all manner of private torture and terror informs us of the persistence of cruelty and coerced gratification of desires. I can cite my own experience of terror as affording me recognition of the signs of trauma in others. I may not have been tortured in the institutional sense that is systematic and professional in method. Nor was I the target of an explicitly political interrogation. I am, however, the survivor of a murder attempt--a sustained and violent hate crime perpetrated on me in the early morning hours of October, 1981. Jumped from behind in an isolated, dark parking lot, I was too disoriented to resist as I was forced into the confined space of a small car--rolled into a ball against a door that wouldn't open. Without the space to move or the light of sight, I was beaten to a pulp for a duration I still can't recall. I found my only recourse was to fall back into a part of myself I never previously knew existed and have never since visited consciously--a dark space with the contours of a human body as seen from within. In that deep inner space I felt no pain nor saw anything of the world outside me. I could only make out sounds--the words of my assailants--to know that a knife had been produced and was about to plunge into me.

Then, suddenly I was pulled from the car by one of the assailants and dumped onto the pavement. As I emerged from my private space and my eyes adjusted to light, the car sped off. It was only then that I became aware that a chance passerby had spotted the pair and shouted out the license plate of the car. He very likely saved my life. When moments later, as the pain began to pound and my vision became obscured, I saw my reflection in a mirror of the restaurant where I awaited the police. In place of my face was a giant swollen pumpkin. It was a month before I would again recognize myself. A month in which the news reported a spree of serial killings of lone men in isolated parking lots and on dark city streets.

I can recall the event now without discomfort, but the trauma, which for months made it impossible for me to venture outside at night without companionship, still wards me away from any dark enclosed space. And I still stop outside my door and without thinking look in all directions before proceeding out at night. I often look behind me when on a dark quiet street, and always look discreetly behind the seats of cars before entering. I relay all this because the experience has sensitized me to the signs of similar aversions in others. I recognize a hesitancy and aversion more acutely. I can't guess what the aversion is to, only that I see something others don't seem to notice. And though I'm perfectly aware that some of my assumptions may be a matter of my own projections, I also hear in the voices of those who object to the depiction of violence in films and other art forms, an abuse of children or women. This happened recently in my conversations with opponents to the film Zero Dark Thirty, when I found myself wondering how many of these critics, especially those conveying a rage that cannot be explained by having heard accounts on a film most refuse to see, are survivors of their own private terrors inflicted on them?

I'm not suggesting that all accounts of torture and terror require basis in direct experience. Our demands as a civilization unblemished by a widespread, collective trauma--the kind only knowable through war on home soil--means that we must depend on news conveyed by reporters and commentators who, without the experience of collective trauma, can do no more than aim for an objectivity that keeps them open to testimony of first-hand accounts. But a reporter or commentator isn't expected to put the trauma of others into a format that is universally understood. That is the role of artists. And it is arguable that the artist who has experienced or witnessed terror or torture is best equipped to translating the trauma of such infliction and injury into universal signage and context.

Experience is an expectation that becomes more acutely required when the art in question represents the accumulated effects of torture and terror sustained over a lifetime. Who, we reason, can share such rare and disfiguring traumatization but the survivor of terror, or the intimates and perhaps the trained professionals sharing their recovery. It is why audiences by nature pay a higher regard to the first-hand account of sustained trauma. The regard accorded the poetry of holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel needs no explanation. Or the visual art of Videla Godoy, who was imprisoned and tortured during the Pinochet dictatorship and later kidnapped by Argentinean police.

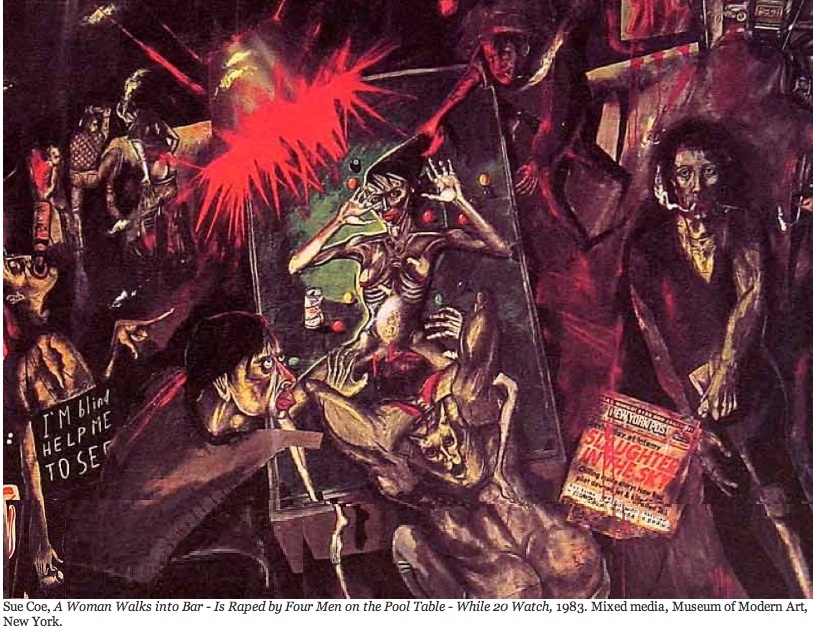

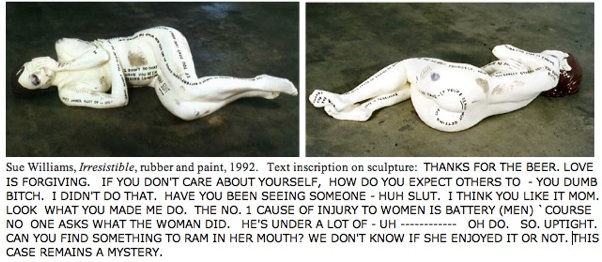

Our regard naturally is drawn to the evocative and powerful photography of Nan Goldin and the sculpture of Sue Williams, both reflecting the artists' own physical abuse by male lovers. But then much of that regard accumulates around such artists because their authority in terror and torture is articulated or embodied in forms mindful of the universality of trauma, and the struggle with, and in the fortunate escapes from, extreme cruelty. Sharing their experience with the public is only the first step, excruciating as it may be. Making audiences around the world empathetic to their experience is the more formidable test of their skills as artists.

On the other hand, we know scores of artists and journalists capable of translating the experiences and accounts of others into powerfully compelling and transformative testimonies. Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman, in his play Death and the Maiden, makes tangible the demons plaguing a woman upon her chance encounter with a man she believes tortured and raped her daily while incarcerated under the Pinochet regime, even though she was blindfolded whenever in his presence. Kirby Dick's 2012 documentary Invisible War, built up a formidable indictment against the US Military for its complicity in the rapes and assaults of tens of thousands of US service women.

Death and the Maiden, the 1994 film by director Roman Polanski, based on the play by Chilean playwright, Ariel Dorfman. When fate unites

a Chilean torture survivor (Sigourney Weaver) with a man she suspects to be her torturer (Ben Kingsley), the victim becomes the victimizer.

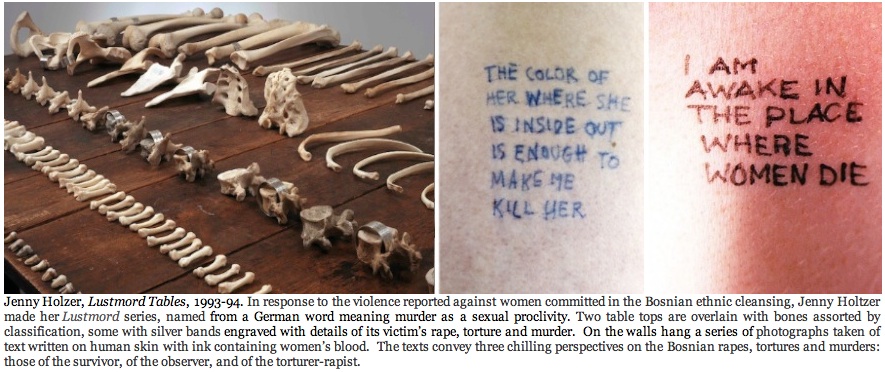

Then there is one of the most chilling art exhibits this writer has ever encountered, that by Jenny Holzer, whose Lustmord series, named from a German word meaning murder as a sexual proclivity, consists of no more than two table tops overlain with bones assorted by anatomical classification, some with silver bands engraved with accounts of women raped, tortured and murdered in Bosnia. On the walls hang photographs taken of text written on human skin with ink containing women's blood. The texts convey three chilling perspectives on the Bosnian rapes and murders: those of the survivor, of the observer, and of the rapist--all executed while Holzer remained safe thousands of miles away.

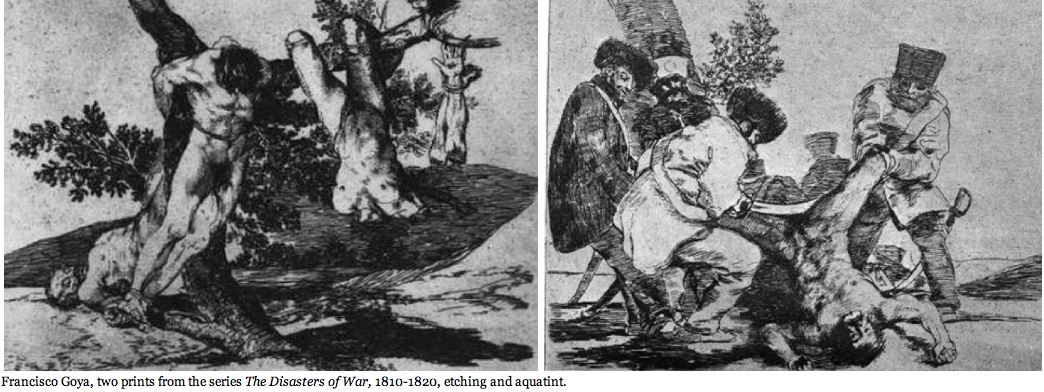

In between the experienced and the received accounts are those artists who lived through the traumas of terror and torture, yet remained personally buffered from the atrocities. Chief among them is no less than the first great artist of modernity, Francisco Goya, whose etchings and aquatints from The Disasters of War, made between 1810 and 1820, catalog the inhumanity of the Napoleonic Peninsular War consuming France, Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom. Besides being regarded as the superlative record of torture and terror, Goya's renderings establish him as the first visual journalist of an in-depth and sustained account of war, a fact made more remarkable by his work preceding the invention of photography by two decades. And yet, mindful of how dangerous his account was, Goya was never able to share his greatest achievement with even his intimates, and the public would not view The Disasters of War until decades after his death.

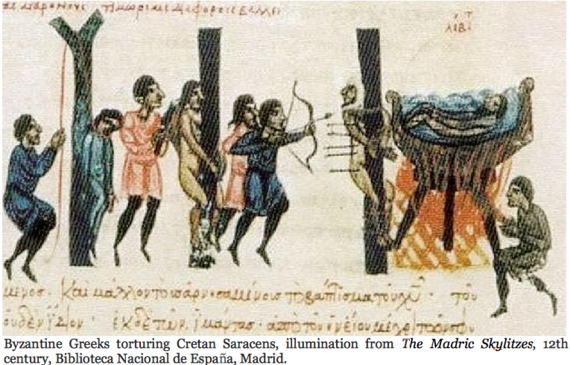

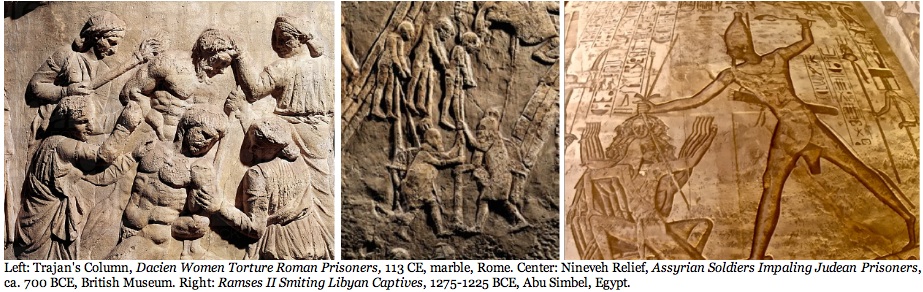

All of which underlines Goya's most significant break with the past. For The Disasters of War is also the first significant account of war made by an artist under his own private auspices--that is, not as an agent commissioned to propagandize this history of a victorious state, as all prior records of torture and terror throughout history had been. Goya's testament also counts as no less than the first truly universalist vision void of nationalistic, ethnic, and religious ideology. The images may be confined historically to European antagonists, but what makes them universal is that Catholics and Spaniards among whom Goya lived are shown to have been no more compassionate and no less cruel than their enemies. Goya's observations have become the standard of objective picture making for all media, a standard dividing the modern from the premodern in terms of image making for the joint effort of history and art.

It is curious, then, that two centuries after Goya's renderings established the now time-honored precedent of presenting the world a testament of torture and terror unflinching in its graphic directness, that the scenes of torture in Zero Dark Thirty would be misjudged as endorsements and apologies for torture. It is especially curious considering that the torture is applied to terrorists proven to be complicit with the deaths of thousands worldwide--men who either personally tortured and terrorized human beings or who supplied such men with the resources they required to carry out their inhumanities.

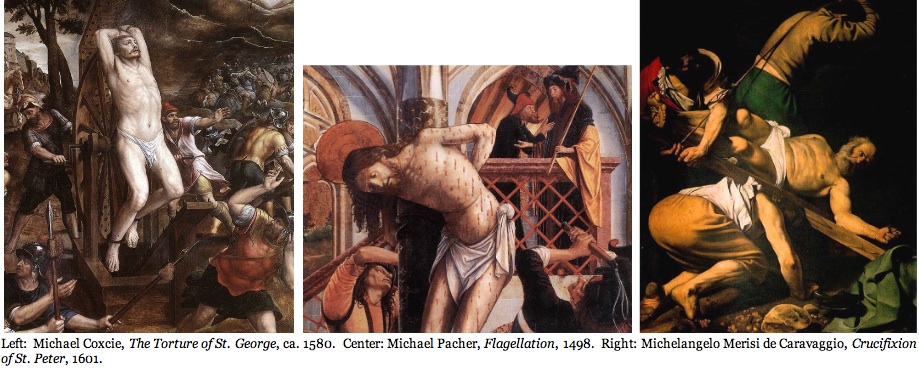

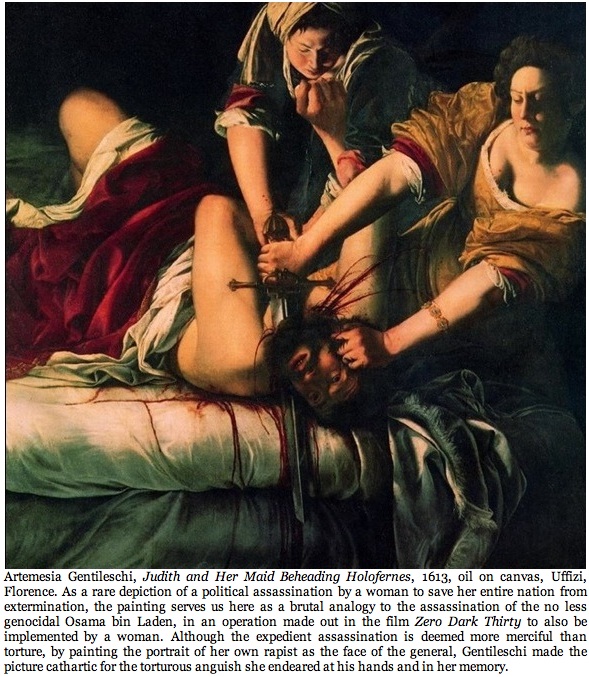

Of course, the more noble art depicting torture and terror does so to drive home the moral conviction that torture and terror should be averted at all costs. But such art also has another purpose: to act as a cathartic release, a powerful healing agent for those of us driven to extremes, mostly in our minds and hearts, but for some in desperate acts of revenge, in a quest for justice and prevention of further terrors. We have precedence for such art from the Renaissance on. Chief among them are the many depictions of the biblical story of Judith and her maid beheading the Babylonian general Holofernes, a man intent on annihilating the entire race of Judeans and Samarians. Particularly telling of the power of catharsis is the fact that the most powerful of the Judith and Holofernes compositions--outranking even those of Michelangelo, Caravaggio, and Rubens--is that by the singular Baroque woman artist Artemesia Genthileschi. It is well known that the face of Holofernes is a portrait of the man who raped her. She did not have to kill him because she killed his effigy. This is the power of healing catharsis at work in art. Yet despite centuries of its example, people still cannot understand that art such as Zero Dark Thirty--whose target, Osama bin Laden, is the very image of Holofernes in his genocidal aims--is made with the intent to speed the healing of a civilization still reeling from the terrors he financed.

Here, another of my personal experiences rears itself in defense. I mean my other experience of torture and terror, this time as a witness. It is hardly a distinction, given how many hundreds of thousands of such witnesses to terror and torture inhabit New York and Washington, and by extension of the media, the billions around the world. But each of us share the statistics of 911 differently. I live only minutes away from the World Trade Center site in Manhattan, what is now Ground Zero. I saw the shadow of the first low-flying plane darken the view from my window; heard it crash into the North Tower. I saw from the street blocks away the second plane disappear into the South Tower. I spoke on the phone to friends living beneath the towers, heard them scream as they watched people jump to their deaths. And then I watched both towers implode in a cloud of ash. It is why I and so many like me are astonished that the anti-Zero Dark Thirty camp has shown so little regard to the victims and survivors of this terror and their requirement for justice. I am not here composing a justification, plea, or apology for torture; it is simply a call for us to publicly broaden the scope of our debate to include the historical context that is much greater than an account of government and intelligence. It is an account that for most (those who were then unaware of the US role in unleashing al-Qaeda on the world) begins with the victims and survivors of the 9/11 terror. And it is certainly an account that differentiates between a film that in its depiction of torture attempts to bring about a healing catharsis for us all in place of a personal, vigilante revenge fantasy.

Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal open their film by contextualizing the torture by Americans with the terror of al Qaeda. Again, the contextualization is not justification, legitimization, normalization, or endorsement of torture. It is for establishing an historical account of what facts stand out from the quagmire of denials and contradictions issued by our own government for the eight years that the Bush administration euphemized its torture of enemy detainees as the employment of "enhanced interrogation techniques."

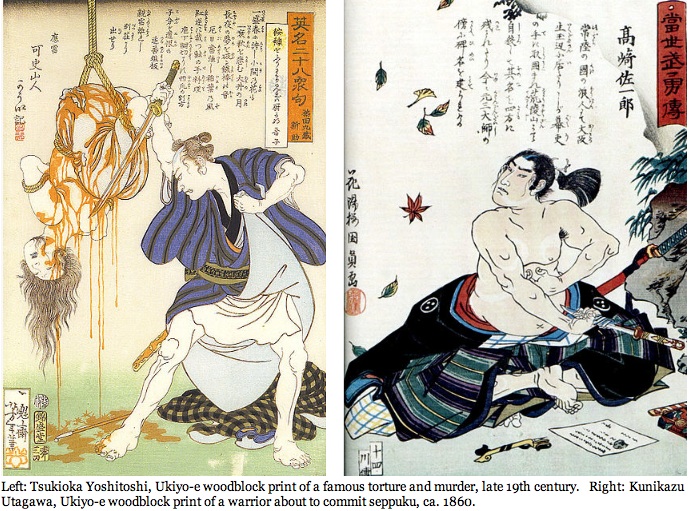

We should as a democracy bear in mind the irony that the imagery of torture and terror is always outlawed by the very powers most reliant on torture and terror to compel and perpetuate the submission of the populace under its sway. We should remember also that under the most brutally sadistic powers, the artists who depict torture are, if lucky, censored; if unlucky subjected to the very tortures they depict. We who live in democracies do the reverse: We outlaw the torture and terror while in principle protect the rights of artists to depict them.

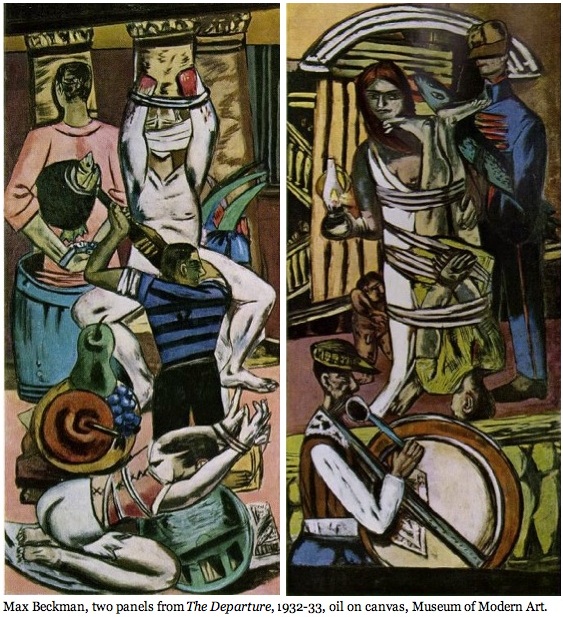

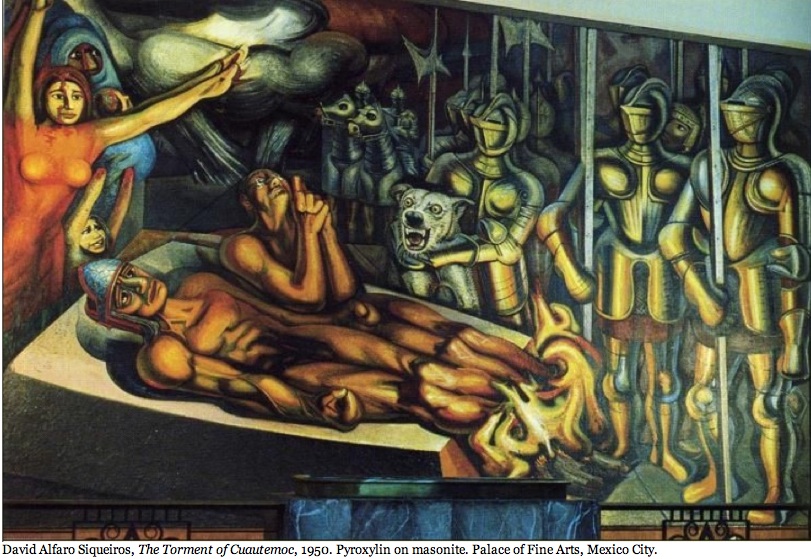

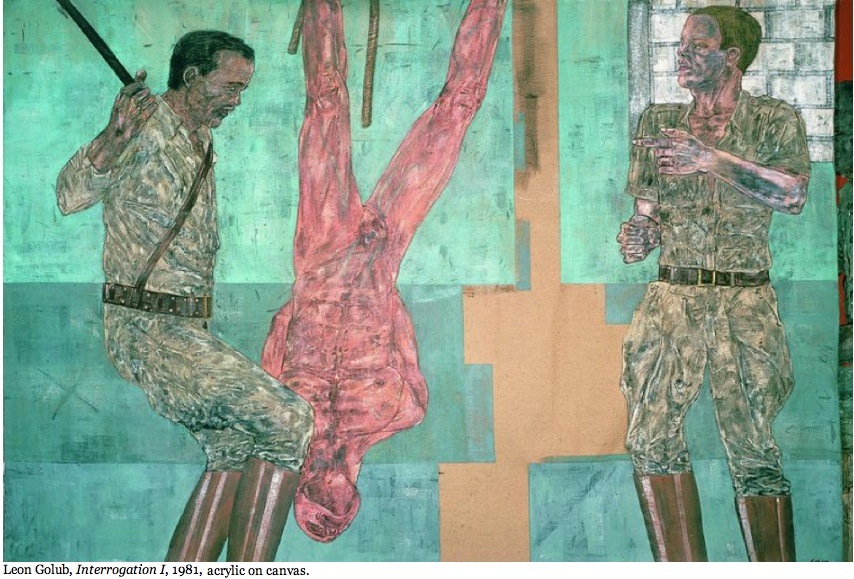

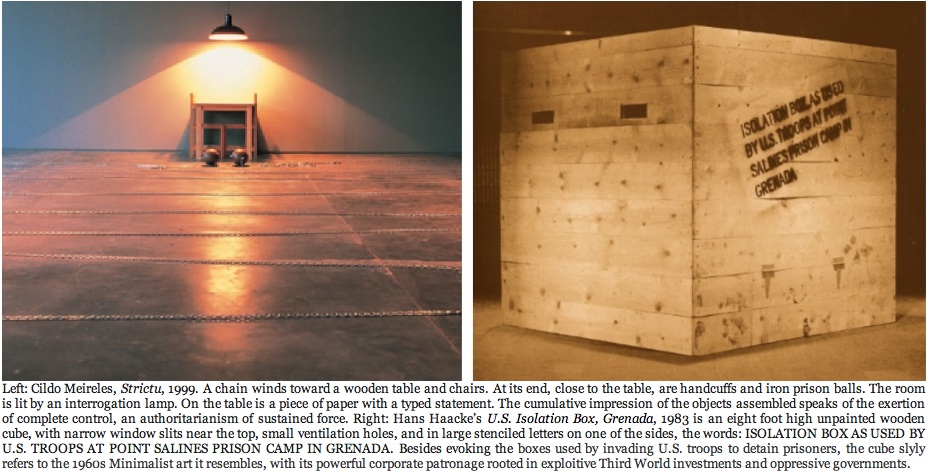

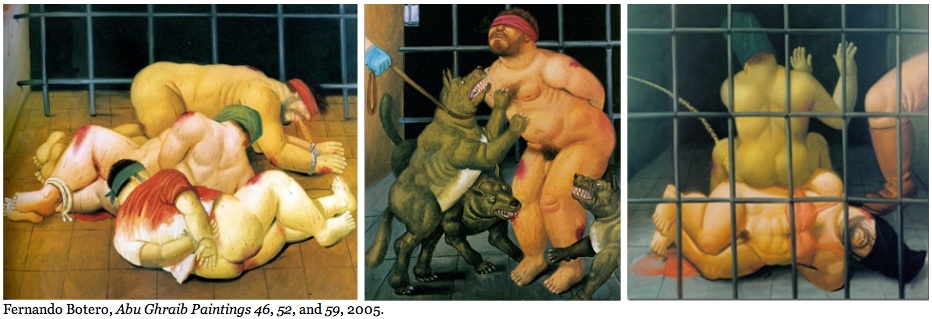

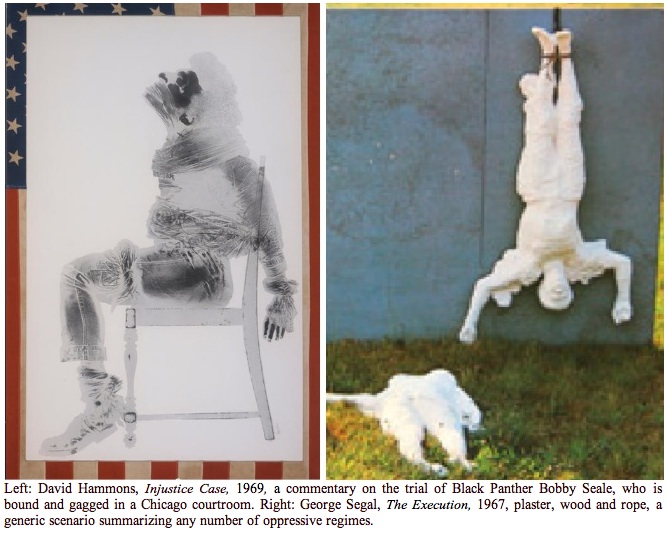

One of the principles of the artists represented here visually regards such direct and frank portrayals of barbarism as being fundamental to exorcising humankind of such real-life terrors. We hold that a population who looks at the torturer and the terrorist squarely in the eye through the portal of art -- be it in imaginary or journalistic accounts -- is less likely to look away when confronted with a government that inflicts torture and terror. We looked away throughout the first decade of this millennium. And as Andrew Sullivan has pointed out, it is Zero-Dark Thirty's eye-to-eye account that has forced us to take a look at ourselves for having both tolerated the Bush administration's criminal actions, and today allows such actions to go unpunished.

Just as Goya shows us how his own people were complicit in the inhumanities of torture and terror, so does Bigelow. For that matter, so do most the artists shown here. The valid argument concerning Zero Dark Thirty, as of all art responsibly portraying torture and terror, isn't whether or not torture is right or wrong. The artists already know that decent human beings carry that information within them. It is innate to our survival and the survival of every living being on the planet. The valid argument is that, whether it is due to experience or empathy, the artist is compelled to show the rest of us the reality that barbarism and terror will persist in human enclaves despite all our efforts to calm and quiet it. The seeds of fascism and sadism are within all of us; they show their presence discreetly in our narcissitic desires and expectations for others--even if we are only able to realistically assert an intimate sphere of control. The prompting to control one's environment is embedded within our nature and nurture.

Bigelow has thought about fascism a great deal. In 2009 she went on record in an interview with the New York Times' Manohla Dargis concerning her aim as a filmmaker to depict how "fascism is very insidious, we reproduce it all the time." This is one of the more subtle yet central strains of thought coursing through Zero Dark Thirty. It's why Bigelow chooses to depict events as they happened and make room for us to reflect on them without cuing the viewer on what to think.

I see both in Bigelow's statement and in her film an admission that there is no art--there is no communication--that is not propaganda. The very act of expression is a will to make others see what we see. To be against propaganda is to be a propagandist against propaganda. The only way to minimize this contradiction is to remain neutral in the act of depicting a politically- and morally-charged scene. Our objection should thereby come only with the degree to which the communication--in our consideration the art--approaches a tyranny of depiction, even if it be the kind of entertainment directing the viewer's regard for what is seen and heard in a film--what most conventional directors do. But in her concern for the insidiousness of controlling impulses, Bigelow refrains from directing our viewing.

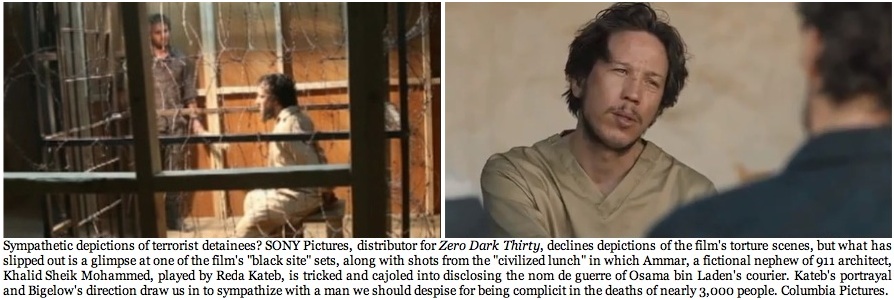

To this viewer, however, Bigelow portrays the tortured detainee Ammar sympathetically. He may be no more than a fictional, composite character, but he is no less described as being the nephew of 911 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed and the dispenser of funds to the 911 hijackers. Bigelow appears to have chosen actor Reda Kateb for his youthful good looks and pleasant demeanor--qualities that easily draw out our sympathies. His longish hair and anguished face even evokes the paradigmatic Hollywood Christ tortured and crucified in its myriad cinematic passion plays. Cynicism aside, Ammar, as a man complicit with the death of nearly 3,000 people on 9/11, should not be a sympathetic character, but he is made so by Kateb's portrayal and Bigelow's direction.

It should be enough for us that she directs the scenes that add up to a coherent narrative about the real powers directing our lives. And we shouldn't kill the messenger for letting us know that we in our inattention or our apathy have been complicit in allowing our elected officials to employ terror and torture while absurdly justifying their actions with the pretext that the end of terror and torture justifies such recourse.

To read public statements made by the Bush and Obama administrations, CIA and Congressional officials between 2008-2011 that inform the film, see G. Roger Denson's post, "Zero Dark Thirty Account of Torture Verified by Media Record of Legislators and CIA Officials."

To read more by G. Roger Denson about Zero Dark Thirty and the social and political responsibility of artists, see his post, Zero Dark Thirty: Why the Film's Makers Should Be Defended and What Deeper bin Laden Controversy Has Been Stirred.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.