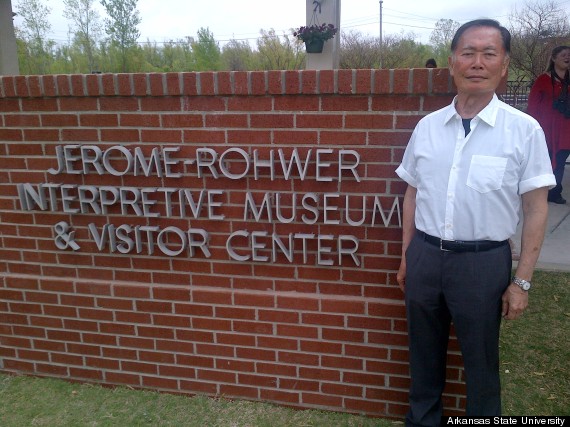

Last week, just before the attacks in Boston, I took a pilgrimage. I

traveled to Arkansas to dedicate the Japanese American Internment

Museum in McGehee. The town lies between two places of great sadness:

Jerome internment camp to the southwest, and Rohwer camp to the

northeast. Over seventy years ago, my family and I were forced from

our home in Los Angeles at gunpoint by U.S. soldiers and sent to

Rohwer, all because we happened to look like the people who bombed

Pearl Harbor. I was just five years old, and would spend much of my

childhood behind barbed wire in that camp and, later, another in

California called Tule Lake. One hundred twenty thousand other

Japanese Americans from the West Coast suffered a similar fate.

I was the keynote speaker at the dedication ceremony of the museum. A

number of internees attended with their families, as well as about 500

people, primarily from Arkansas, along with historians from throughout

the United States. After the dedication ceremony, we moved on to the

actual Rohwer camp site about 20 minutes away.

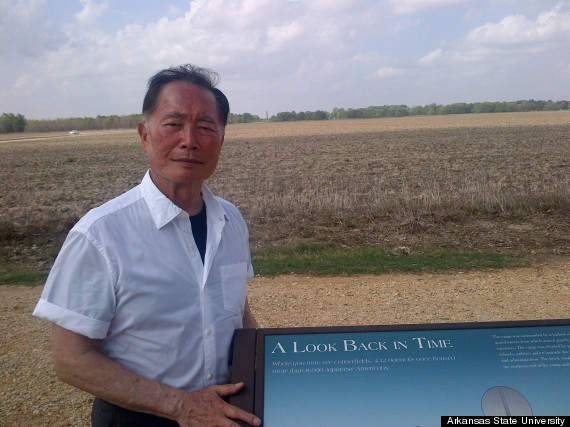

Almost nothing remains where the camp once stood. We went to dedicate

a historic marker, along with half a dozen audio kiosks. It was

admittedly poignant to hear my own voice narrating from those kiosks

about the importance of each specific site, marking ground where we

had been held against our will, without charge or trial, so long ago.

One of the audio kiosks is placed just about at the site of the crude

barrack that housed my family and me -- block 6, barrack 2, unit F. We

were little more than numbers to our jailers, each of us given a tag

to wear to camp like a piece of luggage. My tag was 12832-C.

I have memories of the nearby drainage ditch where I used to catch

pollywogs that sprouted legs and eventually and magically turned into

frogs. I remember the barbed wire fence nearby, beyond which lay pools

of water with trees reaching out from them. We were in the swamps, you

see: fetid, hot, mosquito-laden. We were isolated, far enough away

from anywhere anyone would want to live.

Today, I recognize nothing. The swamp has been drained, the trees have

all been chopped down. It is now just mile after mile of cotton

fields. Everything I remember is gone.

The most moving of the sites is the cemetery. As a child, I never went

there, yet that is the only thing that still stands from Rohwer Camp,

except for a lone smokestack where the infirmary once operated. The

memorial marker is a tall, crumbling concrete obelisk, in tribute to

the young men who went from their barbed wire confinement to fight for

America, perishing on bloody European battlefields. That day, I stood

solemnly with surviving veterans who had served in the segregated

all-Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most decorated

unit in all the war.

We ended the ceremony with a release of butterflies. They symbolized

beauty confined, first in cocoons, then in a box, but now released,

free to go and be wherever they chose.

As I write this, once again the national dialogue turns to defining

our enemies, the impulse to smear whole communities or people with the

actions of others still too familiar and raw. Places like the museum

and Rohwer camp exist to remind us of the dangers and fallibility of

our democracy, which is only as strong as the adherence to our

constitutional principles renders it. People like myself and those

veterans lived through that failure, and we understand how quickly

cherished liberties and freedom may slip away or disappear utterly.

Places like Rohwer matter, more than seventy years later. And so, we remember.