For the past few weeks, I have been observing reactions (from all sides) about Europe's debt crisis, and its responsibility for the U.S. market decrease. It has made me wonder: could a worsening of the European crisis drag the United States and the world into a catastrophe worse than the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers?

The European sovereign debt crisis has far-reaching implications: if it were only Greece, or even Portugal and Ireland, it would probably have a limited impact. Unfortunately, the contagion of other countries seems to be spreading to Spain and Italy. The market reaction to rumors of a possible downgrading of France's sovereign debt rating in August showed how sensitive world markets would be to such an event.

The brave attempts of the European summit of July 21 and the Sarkozy-Merkel meeting of Aug. 8 were lacking in both substance and action, and investors were deeply disappointed. The credibility deficit of the European leadership seems insurmountable at this point, as their statements and subsequent actions are simply contradictory

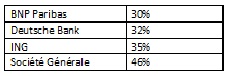

The European banking situation is much more troubling. It is actually scary. The largest Eurozone banks lost between 30 and 50 percent of their market capitalization since July 1.

Since the July 21 summit that was supposed to have resolved the European crisis, Eurozone banks lost the following:

A risk of European economic recession is not excluded. France and Germany announced a zero growth rate for the second quarter, and Greece is currently suffering from a 5-percent recession.

The combination of these three factors explains the apprehension of investors and capital markets toward Europe. Although it is a European problem, could it create issues outside Europe? The most immediate risk is through the banking system. Should the current banking situation lead to a liquidity crisis, we would revert back to August 2007, when banks no longer trusted one another. The interbank financing reached unbearable levels of interest rates at that time, and Central Banks were the only substantial liquidity provider.

What ammunition would be available to counter such a crisis?

The Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank are not in the same position as in 2007. Both have grown their balance sheets at record levels. The assets they hold are not all of prime quality. Their situation is far from being as solid as it was four years ago.

Last but not least, at the current levels of indebtedness, government financing is no longer available for bailouts. In Europe, the guarantees of the European Fund of Financial Stability are increasing the indebtedness of the guarantors: 37 percent of those guarantees are granted by Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland, who themselves are in difficulty. The importance of France (20 percent) and Germany (27 percent) as guarantors is therefore crucial. Unfortunately, the French indebtedness (82 percent of GDP) and budget deficit (7 percent in 2010) make its own creditworthiness vulnerable.

This short review of the European situation cannot hide the risk of further deterioration. European countries ought to make serious improvements to their fiscal situations in their 2012 budgets. Their failure to do so would not only aggravate the European decline but start a new global crisis. Will they have the courage and the consensus to do so? Based on the last 18 months of Greek crisis, one is allowed to have doubts.