Point of view is everything. Whether one is referring to the crafts of of screenwriting, poetry, or journalism, the eye of the storyteller is a window to a previously unobserved universe. The art of "telling" embodies spiritual responsibility.

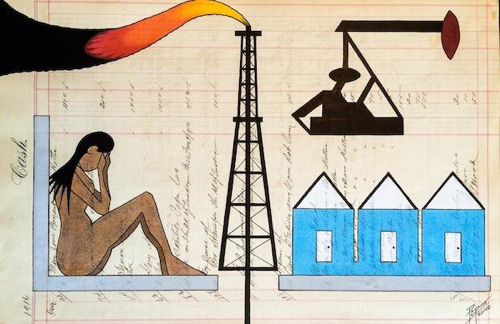

Graphic Courtesy of John Pepion and Winona LaDuke

I learned this lesson while delivering hay.

A group of exhausted but determined Native riders and their horses were camped at a remote farm near Pine River, Minnesota late this summer. The "Love Water, Not Oil" tour, sponsored by Honor the Earth to draw attention to the routing of the proposed Enbridge Sandpiper Pipeline, was nearing the end of a two hundred mile ride through the lake country heartland. Winona LaDuke called and asked if I could find ten bales of hay to make certain their horses had enough forage in case pastureland was unavailable on the last leg of the ride.

Thomas Pope and his wife, Freya Manfred, happened to be visiting me when I got the call, and both were eager to join me on the hay delivery errand. Tom is a screenwriter of significant accomplishment, and Freya is an award winning beloved poet and memoirist who happens to be the daughter of Frederick Manfred. Manfred has been compared to Louis L'Amour. His storytelling focuses on the American Midwest and the western prairies. The borderlands of Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota and Nebraska became his fictional "Siouxland."

This is Anishinaabe country. This is the land inhabited by the characters in LaDuke's epic book, Last Standing Woman, that most of you have probably never heard of. Go out and find a copy. It will change your life and your point of view.

Art was destined to meet reality as our pickup loaded with hay lumbered down the back roads of Minnesota to LaDuke's encampment.

In the Anishinaabe universe there are eight layers of the world--the world in which we live, and those above and below. Most of us live in the world we can see. What we do, however, may intersect with those other worlds.

The quote is from LaDuke.

As a journalist, I am trained to view the world with a dispassionate eye. I fear that the discipline involved offers nothing more than what one sees with eyes clouded by cataracts. That is the world I see. The spiritual depth perception is often missing.

The screenwriter and the poet live in worlds that intersect with the universe LaDuke writes about. There are other worlds. There are other ways of looking at things. There are worlds above and worlds below, and the "Love Water, Not Oil" effort lived and breathed in those worlds. I am not sure I communicated that while writing about the pipeline this summer. My writing did not intersect properly with the rich, multi-layered universe of the First Nation indigenous peoples.

As Tom, Freya and I drove into the camp with nourishment for the horses, we each had a point of view that, when combined, offered spiritual depth.

The journalist in me saw the difficulty of the journey faced by horses and riders. It is not easy to ride two hundred miles and camp with your horses in unfamiliar terrain. I saw tents, and corrals. I smelled breakfast being cooked over open fires and fretted about where to put the hay. I wondered how in the world, my worried world, that the riders were accomplishing this dangerous journey.

Tom, the screenwriter, immediately spoke about the romance of the scene. He saw hardy native riders, tents that could have been tipis, and smoke that bathed the encampment in the mist of fascination.

Freya, the poet, spoke to me about the beauty, determination and strength of the people.

Each of us had a unique point of view. Each was valid and complete in its own way, but it was not until I read LaDuke's writing in a three part series running in Indian Country Today, that I understood how we desperately need Indian writers to have a voice in media. Whether it is online or mainstream print media, the Native Voice is lacking in access to the white world.

I wanted to write a story about strength and resilience. I wanted to write a story about the singers, the horse people, and the earth lodge builders of the Mandan Hidatsa and Arikara peoples, the squash and corn, the heartland of agricultural wealth in the Northern Plains. That's the story I have been wanting to write. But that story is next. The story today is about folly, greed, confusion, unspeakable intergenerational trauma and terrifying consequences, all in a moment in time. That time is now.

This is the voice of Winona LaDuke. This is her point of view, and it is one that a white writer cannot possibly hope to replicate. There are many other native writers, of course, but there is no one who has been so eloquent in telling the story of what big oil is destroying in Indian Country. It is a story of trauma and generational loss.

My effort today is one of convincing the readers of this blog to read the three part series in Indian Country Today. You can access it here.

After you read the series, reflect on its unique point of view. Listen to your heart, and your heart will bring you to a universe with many layers.

The story needs more than telling. The story needs listening.