By Erin Lee Carr, Glamour

How do you say goodbye to your father? Erin Lee Carr, daughter of the New York Times' David Carr, did it by focusing on the wisdom he left behind.

I was in the passenger seat as my dad steered our family's SUV in the direction of my first internship, at Fox Searchlight Pictures. He ignored the car wedging into our lane and turned my way. "Who's your supervisor?" he asked. "Who's head of the company? What films of theirs do you like?"

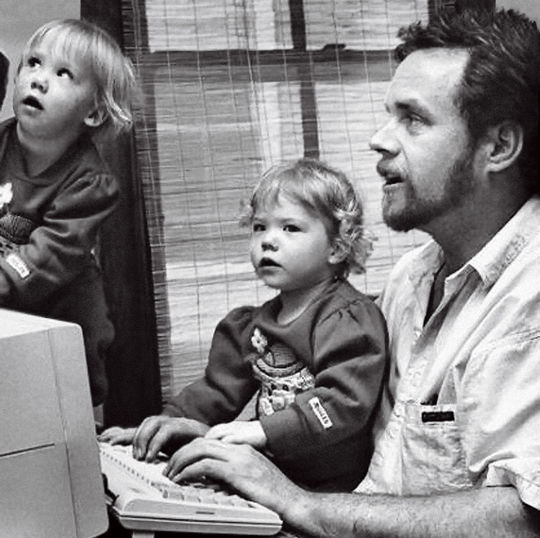

Family Man: David Carr, with Erin, center, and her twin, Meagan, when they were about four (Photo: Courtesy of Erin Lee Carr)

I mumbled something about how I'd loved the acerbic side of Juno, which the studio had put out about a year earlier. My dad shook his head, lit a cigarette, and said, "No one is going to take you seriously if you don't take the job seriously. Do your f--king homework."

I hadn't even started yet, but this was still a defining moment in my career. My dad's message stuck with me: Do the work and know what you're talking about.

To our family he was a wise, generous and devoted father. He had a remarkable voice, a raspy one that often ended in a laugh. To the world he was a famed media columnist for The New York Times, author of the memoir The Night of the Gun, and star of Page One, a documentary about the Times.

His life was colorful, with stints in restaurants and on drugs and, later, with babies and bylines. He often said to me and my twin sister, Meagan, "Everything good started with you." Being a dad to us and our little sister, Maddie, was a chief joy, in large part because it pulled him out of the depths of addiction and toward the man he would become.

I didn't know David the drug addict; I knew David the loving dad.

As I followed him into the media world (documentary film is my field), he counseled me on the best way to get my voice heard. "Don't be the first to speak," he would tell me. "But if you do, say something important."

I took notes every time we spoke on the phone about my work, and if he didn't hear the click of the keyboard, he'd ask why I wasn't committing his advice to paper (or pixels). The day before he died, I had a work issue and called to ask if he had five minutes to help me sort it out. His answer: "I always have time for you."

He was constantly typing, talking, learning, moving. He had a hunger for knowledge, trivial or monumental, and he expected me and my sisters to share that curiosity. When I was a teenager, he assigned books for us to read. He issued quizzes to ensure that our vocabulary was as extensive as he thought it should be. (The family later begged me to cut back on my use of copacetic.) He taught us to challenge information, places, and people -- and never, ever to settle for less than the best of anything. He never did.

The night of February 12, 2015, I watched my dad speak onstage in New York City to filmmaker Laura Poitras, journalist Glenn Greenwald, and (by way of video conference from Russia) government-secrets leaker Edward Snowden. After the talk was over, I sneaked backstage to give him a bear hug. He introduced me to Greenwald, who said, "Your dad is your biggest fan." I quickly replied, "I'm his."

We stepped outside, into the brutal winter hellscape that is February in New York City. My dad had quit smoking only four days before, and he looked exhausted. I gave him a hug and told him I loved him. I left for the subway; he got into a cab.

It was the last time anyone in our family would see him alive.

I got the call from my stepmom. My dad had been found unconscious on the floor at the Times. He hadn't been in the best of health. If you knew about his bout with cancer and years of substance abuse, you might have expected this day would come. But I never imagined it. To me, Dad was invincible.

I rushed to Mount Sinai Roosevelt hospital, sobbing in the cab as I called my best friend. When I paid the fare, my driver mumbled, "I'm sorry." I nodded but had no words.

I walked into the hospital and found out: It was over. My dad had died.

My stepmom and I went to his bedside, but before I could say goodbye, my phone started buzzing. Word had broken that my dad had passed away. Someone had tweeted about his death. I was filled with rage.

Couldn't I have at least 30 seconds to comprehend what had happened without having to hear the Internet's take?

Couldn't the loss of the most important man in my life be my own, if only for one quiet moment?

My stepmom and I raced to call my sisters, reaching them, thankfully, before the news went viral. It felt unfair to rush through the most difficult words I would ever say just so I could beat the Internet.

As I sat in the grief room, my phone still buzzing, I couldn't help but look at the things that were being said about my dad on Twitter. Over the course of the following week, countless tweets and beautifully crafted pieces of writing would appear on the Web and in print. For The Atlantic, my dad's friend and protégé Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a moving tribute called "King David," about how powerfully motivating it was to have someone like my dad rooting for him. The day after he died, my dad made the front page of The New York Times -- in Irish tribute, we hung it on our front door.

Hundreds flocked to his wake and funeral -- musicians, weirdos, writers, media tycoons, schoolteachers, coworkers, and gangsters. I realized how many roles my dad filled for other people. He was a friend, secret sharer, mentor, boss, ally. Several women (myself included) spoke about my dad's devotion to feminism. My father was one of seven kids from an Irish Catholic family -- he would have loved the attention.

The other day I got some good news and, wanting to share it, reflexively typed "dad" into my phone. There are moments in grief when the finality sets in, and here it was: I would never be able to hear his voice again. But I've realized, strangely, that instead of resenting the Internet, I'm grateful for it.

I can tap Dad's name into Twitter and be flooded with the lessons he shared with others, including some he never had a chance to share with me. I don't know what it's like to lose a parent who didn't lead a public life. I'm just glad my dad was out there in the world, leaving an impression on everyone he met.

The Internet can be intrusive, yes, but it can also be a voice of comfort -- and, in my case, a close friend leaning in to whisper, "You know how you thought your dad was the greatest guy in the world? You were right. Let me tell you why."

Erin Lee Carr is the director of the HBO documentary Thought Crimes.

More from Glamour:

What All Women (and Men) Can Learn From Sheryl Sandberg's Marriage

30 Hair Color Ideas to Try Now

9 De-Bloating Foods for Instant Weight Loss

10 Makeup Tips Every Woman Should Know

10 Things He's Thinking When You're Naked

What Men Really Think About Your Underwear

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact HuffPost Women

Contact HuffPost Women