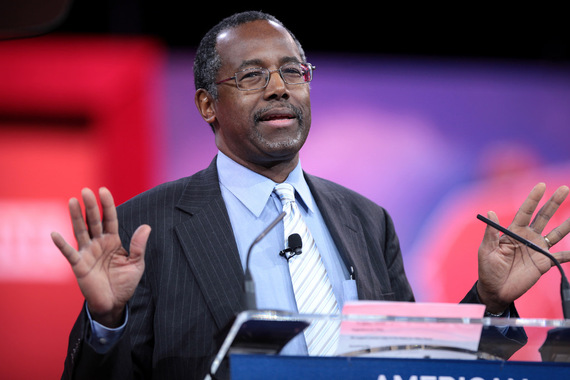

Ben Carson really needs to stop talking about what people should and shouldn't do when confronted by an armed criminal. First, he criticized the victims and bystanders at Oregon's Umpqua Community College--and by implication, those at other mass shootings--for not doing what he'd have done in that situation: "Not only would I probably not cooperate with him, I would not just stand there and let him shoot me." Carson said he'd have attacked the gunman and encouraged everyone else around him to do the same.

To his credit, when Carson was in just that kind of situation, that's exactly what he did. Except: No, he didn't. What he actually did sounds like the dictionary definition of what it means to cooperate with an armed criminal. Here's Carson in his own words: "I have had a gun held on me ... Guy comes in, put the gun in my ribs. And I just said, 'I believe that you want the guy behind the counter.'"

Carson's fantasy scenario is the one that reflects the way many Americans approach the issue of guns. The fantasists have come to believe that if they had a gun, they'd be able to ensure their own safety and the safety of those around them. What they refuse to see is that if you want to make yourself safer, the evidence shows that buying a gun is the last thing you should do.

One way of looking at these issues is through the prism of laws. The data strongly suggests that gun control works. A recent study from the National Journal found that the states with the lowest rate of gun deaths in 2013 (i.e., homicides, suicides, accidental gun deaths, and firearm deaths from shootings where intent could not be determined) were states with the tightest gun laws. Those include laws that mandate a permit to buy a handgun, laws that extend to private sales the requirement for a background check (thus closing the "gun show loophole"), and laws that make it difficult to acquire a concealed carry permit.

For example, the six states with the lowest gun death rates from lowest to highest are Hawaii, Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey. Those states have rates ranging from 2.5 to 5.7 deaths per 100,000 people. The six states with the highest gun death rates, starting with the highest are Alaska, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and Wyoming. Those states have rates ranging from 16.7 to 19.8 gun deaths per 100,000. We are not talking about small differences here.

The numbers also confound the (incorrect) stereotype that urban areas are more dangerous to live in than non-urban ones, as the six states with the lowest rates were all significantly more urbanized than the average state. Meanwhile, the six states with the highest rates were among the least urbanized, according to census data. One other point: The District of Columbia--a 100 percent urban "state" that conservatives love to cite (again, incorrectly) as evidence that gun control doesn't work, actually has a lower gun death rate than 38 out of 50 states.

Finally, a Johns Hopkins study examined the effects of the 2007 repeal of a Missouri law that required a background check in order to lawfully purchase any gun, including private sales. Even after it "controlled for changes in policing, incarceration, burglaries, unemployment, poverty, and other state laws adopted during the study period that could affect violent crime," the study found that between 2008 and 2012 the law's repeal was responsible for a 14 percent increase in Missouri's murder rate when spread across the state's counties. The state also saw a 25 percent increase in the gun murder rate.

During this period, non-firearm related murders in Missouri did not increase, murders did not significantly go up in any of Missouri's neighboring states, and the national murder rate dropped 5 percent. Combine these data points with the fact that 90 percent of Americans continue to support universal background checks, and the fact that we cannot pass a law mandating them becomes even more infuriating.

Beyond the effectiveness of laws is the question of the effectiveness of gun ownership itself, at least for those who think buying a gun will make them safer. Again, the answer is clear: Having access to a gun makes a person less safe. A meta-analysis of existing studies done at the University of California-San Francisco found that a person who has "access to a firearm" is three times as likely to commit suicide (not attempt, but actually take his or her life), and twice as likely to be murdered when compared to someone without access to a gun. When broken down by gender, men with access to guns are four times more likely to kill themselves than those without, and women with access are three times more likely to be murdered. For just about everyone, if you want to make yourself safer: Don't buy a gun.

These facts may not be common knowledge, but either way, the question remains why so many of us are unable to let go of the kind of fantasy that tumbled out of Ben Carson's mouth. That fantasy appeals to a strain in American culture that venerates the rugged individual, the person who masters their environment. There is a certain hyper-masculine approach to life that purports that one really can achieve control over one's surroundings.

This isn't about the National Rifle Association, and other lobbying groups who exercise disproportionate power in our political system. They merely represent the interests of the gun and ammunition industry that funds them. This is about the power of the cultural and psychological myth of individual control. This myth helps, at least in part, to explain why individuals ignore or deny the very real risks of gun ownership while exaggerating the virtually infinitesimal likelihood that they will ever: a) be in a situation where brandishing a weapon would be both necessary and helpful, and b) actually be able to use one to stop a person aiming to do them harm, as opposed to either shooting an innocent and/or themselves, or having the gun taken from them and possibly used against them.

Two families learned about the risks of owning guns the hard way in just the past few days. In Tennessee, an 8-year-old girl is dead after an 11-year-old boy killed her with his father's shotgun. She wouldn't let him see her puppy. In Ohio, a 12-year-old is dead because his 11-year-old brother shot him accidentally. There were three loaded firearms left on a picnic table while the so-called adults were talking. In reality, it's much more likely that gun owners will shoot themselves, or that another person will end up shot, than that the owner will use it to thwart a criminal. Yet the myth persists.

Some Americans seem unable to accept that there are threats so unlikely to occur that attempting to pre-empt them is more likely to result in harm than the threat itself. Pushing this idea a bit further, it reminds me of the "One Percent Doctrine," a phrase drawn from a remark made by Dick Cheney to describe the Bush administration's approach to terrorism. The phrase is also the title of the book by Ron Suskind on that topic. As Cheney put it:

If there's a 1 percent chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response. It's not about our analysis ... It's about our response.

To a good degree, this thinking parallels how many Americans unconsciously think of gun ownership. If there's a chance--a small chance, the likelihood of which such people inflate by large multiples--that they might come face to face with an armed criminal, they treat it as a certainty. Only by doing so does buying a gun for self-protection make sense.

The common thread is the type of person whose temperament demands action, now (now!), who shoots first and asks questions later. They buy a gun--or invade a country unprovoked--because they cannot accept the idea of doing what seems like nothing in the face of a potential threat, no matter how small. The need to act connects to the myth that by acting they are exercising control. The hardest thing for such people would be to accept that they cannot control every situation, they cannot make themselves 100 percent safe. Such a level of safety does not exist. Such people cannot accept what they see as a "passive" response, even though the data when it comes to guns shows that such a response, i.e., not buying a gun, will make them safer than buying one.

How many of you remember the ending to the movie WarGames? After running scenario after scenario of a nuclear war between the U.S. and the USSR, the computer finally learns a lesson that applies to those who think buying a gun will make them safer.

Having learned that some actions inevitably do more harm than good, the computer ultimately concludes: "The only winning move is not to play."