"To me, the medium is inseparable from the message, or at least an equally interesting part of the message e.g. it's impossible to talk about a medieval manuscript without thinking about how it embodies a whole way of life, with its pages made of animal skin, its ink made of charcoal or berries, the pen used to create it plucked from a goose--all of its materials part of the natural world, just as the e-book embodies our time." --

SteveTomasula

We live in a time when the physical object of the book, marked, as it is, by the process of its making (transubstantiation of natural materials) and use (coffee stains, notes scribbled in a margin, bent pages) is giving way to an apparently immaterial, a-historical, eternally renewable electronic version. Many bemoan the loss, but few seem to comprehend that this is merely an indicator of a far more radical alteration in our perception of time and space.

Steve Tomasula's multimedia novel TOC (design by Stephen Farrell, programming by Christian Jara ), newly re-released as an iPad app, utilizes the same technology that has fostered this shift to create a compelling, thought-provoking work about the nature of time.

Screenshot, Opening Sequence of TOC

TOC opens like a movie with the image of a film strip running over an computer-animated journey through space. As tinny music plays, a voice-over reminds us that the light of stars long past illuminates our future. In TOC, as in the universe, past, present and future coexist. Tomasula utilizes digital versions of both old and new media (computer animations by Matt Lavoy, vintage film clips, text, paintings, rhythmic sound-effects, music and audio narration) to relate the myth of Ephemera, a queen exiled for creating a mysterious clock-like mechanism called the "influence machine" that is blamed for the apocalyptic destruction of civilization. On their new island home, her twin sons Chronos (time) -- the logical, confident, keeper of gravity -- and "slippery" Logos (word) -- who delights in disrupting order -- struggle for dominance. Their quarrel over who is first-born does not end in a final war, but in a never-ending wager, played by philosophers or curious bystanders, in which the viewer/reader is invited to participate.

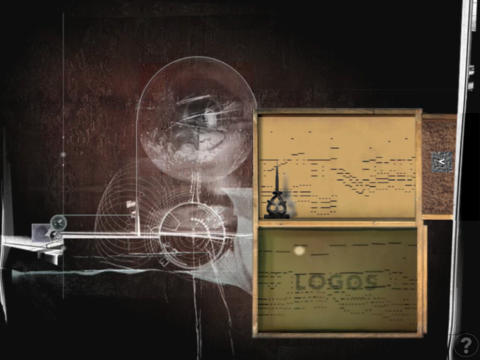

Screenshot of TOC

Dragging a pebble into one of two boxes, ("Chronos" is filled with sand and "Logos" is filled with water), the user reveals a player piano roll upon which the story of TOC is encoded. In the case of "Logos", this consists of fables about the influence machine, movies about time and space, and myths about the peoples of the island (paired with theatrically surreal paintings of nature morte by Maria Tomasula). "Chronos" consists of a voice-over narrated animation about a Vogue model whose husband is kept, suspended in time, on a respirator after a heroin overdose.

Detail of a painting by Maria Tomasula in TOC

Tomasula uses technology to evoke different experiences of time. While the player piano paper scrolls automatically in the "Chronos" section, in "Logos", the user must catch the punch codes as they roll by. Hesitation (time pausing) and desire (time moving forward) are engineered into the process of reading. In "Chronos", dragging the cursor back allows the reader to repeat the story. Thus, repetition, a form of cyclical time, is part of the experience as well.

"From very early on I was thinking about the narrative in terms of storyboarding, and flowcharts, and how the speed at which animations would run would work with certain moods or senses of time embodied in the story. I tried to imagine ways to evoke within the reader different senses of time so that he or she would experience them, not just read about them."

Just as TOC "shatters" time into its "monumental, cosmic, historic, romantic and personal versions," space loses its one-pointed Cartesian perspective, fragmenting into layers as in limited animation.

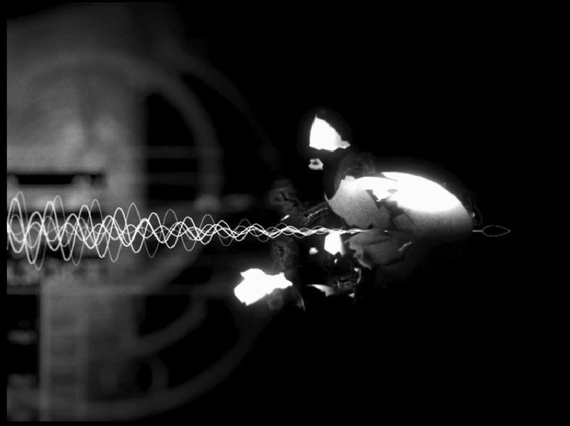

Screen shot of an animation in TOC

In TOC, narrative cohesion is maintained, not through conventional means: plot and character, but through a straightforward user interface and a unified aesthetic experience. As in cinema, the emotional tone is set through music (by Chris Pielak in "Chronos" and Paul Johnson in "Logos".) Perhaps most importantly, Tomasula recognizes and utilizes the logic of the database to convey meaning.

"The materials of a story are always part of the story, or at least they can be--the way the very look of a daguerreotype, or polaroid, or any technology--printing or paper making and inks or the screen of a Commadore 64--conjures up a time and place. All of these things are material for narrative--and by this I mean inherently part of the narrative, not just as decoration or illustration."

Throughout TOC, Chronos and Logos reveal their inseparability. In fact, Tomasula reserves some of his most achingly beautiful prose for the "Chronos" section. Listening to these narrated lines: "but there remained an archeology of flesh, a slackening of epidermis that told of catastrophic weight loss, steady atrophy, a text of sutures on a page of purplish green discoloration that shimmered as beautifully as the trout he used to fish for," I turn back the cursor to listen again.

As the excellence of his writing makes clear, even with the addition of other media, for Tomasula, text is not an incidental conveyance for narrative, but its essential life force.

"I think born digital works, video-poems, machine-writing, and other kinds of non-traditional writing are making us ask--why write text?--and I think one answer will be some version of the answer painters discovered at the advent of performance art, or playwrights discovered as movie making matured: that text, too, is a medium: a really great medium, that can do some things better than other mediums, and every art form is always, no matter what else it is about, at least a little about its own medium."

The model's decision whether or not to keep her husband on life support is complicated by the discovery that she is pregnant. Just as the camera artificially freezes her smile, the flow of time granulates in memory/story and deposits/manifests itself materially in objects and bodies, which harbor both the future (a baby) and traces of time passing (the model's changing, aging body.)

"Just because Time is a human construction doesn't mean it doesn't have aspects that lie outside of language. Being pregnant, the Model realizes that she doesn't have 'all the time in the world' as there is another clock, now within her, running at its own pace, and to its own ends. The oldest conceptions of time are tied to the natural world, of course, days and nights, for example, and so in a sense they are fused with our bodies, our evolution, as we show whenever we cross enough time zones to get jet lagged -- which is one of the interesting ways technology comes in: the way it can expose aspects of time that are invisible to us because they are so much part of our lives they are as natural as breathing. But also how lots of technologies are changing our experience, especially how we experience time, and so shaping how we think about ourselves and each other, and ultimately how we live and what we are."

TOC ends where it began with an image of the cosmos. The mysterious influence machine/difference engine explodes. The user in thrust back into a directionless every-time: the star-filled vastness of space. TOC reminds us how, faced with the unfathomable multiplicity of the universe, we can still use language and storytelling to orient ourselves, and it points out how we might use technology to expand and alter not only how we tell stories, but the stories we tell ourselves.

The entirety of my conversation with Steve Tomasula can be read here.