I often say that watchmaking and architecture are akin. Probably the most irrefutable reference for this is assertion is Le Corbusier whom emerged from his training as a watchmaker in La Chaux-de-Fonds to be one of the pioneers of modern architecture, as we know it today. For those unfamiliar, La Chaux-de-Fonds is a small city in Switzerland, which is the home of the International Museum of Watch Making.

Fast-forward to 2014 in Le Brassus, Switzerland, and rock-star architect Bjarke Ingels, Founder of BIG, has completed the design for La Maison des Fondateurs, an expansion of the headquarters of Audemars Piquet. Readers may be familiar with Bjarke, as I did jump a fence together with Bjarke and interview him on the site of W57 in New York City. I was fortunate to spend some time with Bjarke recently to discuss La Maison des Fondateurs and share some insights with readers today.

Bjarke Ingles, portrait. Photo courtesy of Stephen Voss.

Jacob Slevin: In 140 characters or less, please define your design thesis for La Maison des Fondateurs.

Bjarke Ingels: La Maison des Fondateurs is designed like a clockwork - shaped by its inner workings, the design provides maximum performance with minimum material.

Jacob Slevin: Le Corbusier, one of the world's most renowned architects, was likewise a watchmaker. Did you identify any connectivity between the art and practice of watchmaking and the art and practice of architecture?

Bjarke Ingels: Watchmaking, like architecture, is the art and science of invigorating inanimate matter with intelligence and performance. It is the art of imbuing metals and minerals with energy, movement, intelligence and measure -- to bring it to life in the form of telling time. Unlike most machines and most buildings today that have a disconnect between the body and the mind, the hardware and the software, in watchmaking the form is the content -- the geometric design is what makes the clock tick!

We have carried these principles with us in to the design for La Maison des Fondateurs and have attempted to completely integrate the geometry and the performance, the form and the function, the space and the structure, the interior and the exterior in a symbiotic whole.

Also I'm quite fascinated with the story of how Switzerland became a world-leader in watchmaking. In the 16th century Jean Calvin introduced a ban on jewelry in Geneva. Out of work, all the jewelers needed something else to do. Since the watch was seen as a functional tool it became a loophole in the ban and suddenly the skillsets of a whole profession migrated towards watchmaking.

Traditionally you associate innovation with perseverance -- to fight for your ideas and plow through the obstacles -- but sometimes it is when your road is blocked that you are forced to go new ways and discover new territory. In a way the Swiss watchmaking miracle is a case study in innovation through adaptation.

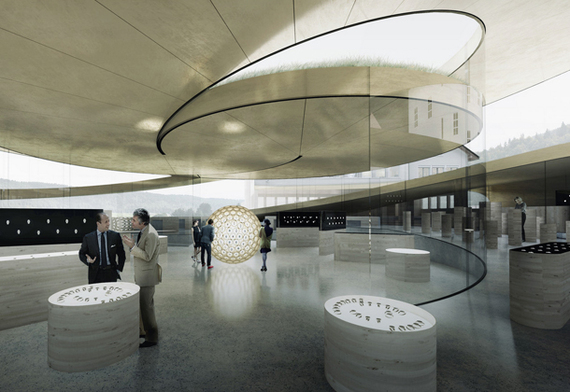

Photos courtesy of BIG.

Jacob Slevin: What is your favorite design moment within La Maison des Fondateurs?

Bjarke Ingels: The curving glass walls are the sole structure of the museum. In compression, glass can be even stronger than steel, but it tends to buckle fatally in a seismic event. However, the continuousness of the spiral museum walls provides geometric stiffness to the sheets of glass and prevents buckling in the event of a tremor.

So as you walk around the museum the gently undulating spiraling roof surfaces seem to be floating above you. The gaps and cracks between the differently sloping roof planes allow glimpses of the surrounding mountains. In a way it is the seemingly magical absence of structure that is the greatest drama of the architecture.

Jacob Slevin: Why spiral?

Bjarke Ingels: The intertwined spirals solve one of the dilemmas of the program. The narrative structure calls for a succession of galleries and workshops, while the logistics of operations requires the workshops to be interconnected. By coiling up the sequence of spaces in a double spiral, the three workshops find themselves in immediate adjacency -- forming one continuous workspace -- surrounded by galleries. The longest possible storyline coiled up in the most compact possible footprint.

Photos courtesy of BIG.

Jacob Slevin: Talk to me about materials.

Bjarke Ingels: The roof and ceiling of the pavilion is conceived as a single sheet of metal - a steel structure clad in brass, continuous in plan but undulating in section to create a series of openings allowing daylight and views to the exhibits. Towards the end of the visit the double spiral intersects the existing museum building providing access to the vaulted spaces in the lower floor and to the attic. The dynamic forms of modern materials, glass and brass, give way for a locally anchored tectonic of straight lines and warm surfaces of wood or stone. Heavy meets light. Soft meets hard. Warm meets cool.

Jacob Slevin is the CEO of DesignerPages.com and the Publisher of 3rings & Otto.