Imagine discovering a lost and forgotten ancient Jewish/Christian writing, one not included in the New Testament, that dates to the earliest days of the emergence of Christianity. For historians of early Christianity or ancient Judaism, there is nothing more exciting -- think of the amazing significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls, or the Nag Hammadi "Gnostic" gospels.

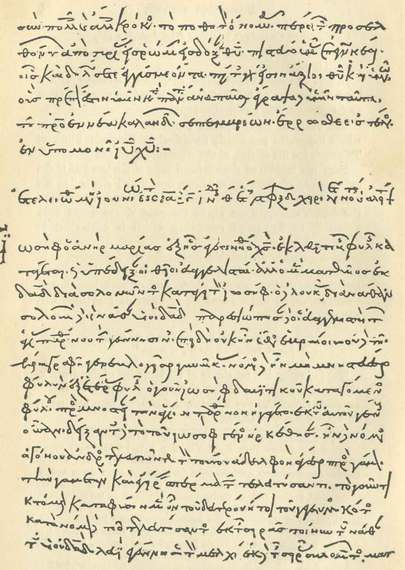

That is precisely what we have in the case of the Didache (pronounced "did-a-kay"), an ancient Greek manuscript discovered in 1873 in a library at Constantinople by a Greek priest, Father Philoteus Bryennios. "Didache" means "teaching," and its full title is "The Teachings of the 12 Apostles." This precious copy of the ancient text, dating to the late first or early second century CE, is mentioned by early Christian writers but had disappeared. Few Christians today have even heard of it, but you can read it online, in several translations with commentary, here. This text allows us a glimpse into a largely forgotten form of early Christianity, one that stands in rather stark contrast to the Christianity developed by the Apostle Paul some decades after the death of Jesus.

The Didache is divided into 16 chapters and was intended to be a "handbook" for Christian converts. The first six chapters give a summary of Christian ethics based on the teachings of Jesus, divided into two parts: the way of life and the way of death. Much of the content is similar to what we have in the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain -- that is, the basic ethical teachings of Jesus drawn from the "teaching" source now found in Matthew and Luke. It begins with the two "great commandments," to love God and to love one's neighbor as oneself, as well as an alternative version of the Golden Rule: "And whatever you do not want to happen to you, do not do to another."

It contains many familiar injunctions and exhortations, but often with additions not found in our Gospels. Here are a few examples:

- "Bless those who curse you, pray for your enemies, and fast for those who persecute you" (1.3).

Many of the sayings and teachings are not found in our New Testament gospels but are nonetheless consistent with the tradition we know from Jesus and from his brother James:

- "Let your gift to charity sweat in your hands until you know to whom to give it" (1.6).

Following the ethical exhortations there are four chapters concerning baptism, fasting, prayer, the Eucharist, and the anointing with oil. The Eucharist in the Didache is a simple thanksgiving meal of wine and bread with references to Jesus as the holy "vine of David," but with no references to the body or blood of Jesus related to the remission of sins. It ends with a prayer: "Hosanna to the God of David," emphasizing the Davidic lineage of Jesus.

There are final chapters on testing prophets and appointing worthy leaders. The last chapter contains warnings about the "last days," the coming of a final deceiving false prophet, and the resurrection of the righteous who have died. It ends with language similar to that used by Jude but taken from Zechariah and Daniel: "The Lord will come and all of his holy ones with him," and, "Then the world will see the Lord coming on the clouds of the sky." Both references to the "Lord" here are to Yahweh, the God of Israel.

The entire content and tone of the Didache reminds one strongly of the faith and piety we find in the letter of James and the teachings of Jesus in what scholars call the Q source.

The most remarkable thing about the Didache is that there is nothing in this document that corresponds to Paul's "gospel" -- no divinity of Jesus, no atoning through his body and blood, and no mention of Jesus' resurrection from the dead. In the Didache Jesus is the one who has brought the knowledge of life and faith, but there is no emphasis whatsoever upon the figure of Jesus apart from his message. Sacrifice and forgiveness of sins in the Didache come through good deeds and a consecrated life (4.6).

The Didache is a precious witness to a form of the Christian faith more directly tied to the Jewish orientation of Jesus' original followers. It reminds one of sections of the Community Rule (1QS) found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which provides us with what is perhaps its best Jewish parallel. Along with the letter of James in the New Testament, the embedded source in Luke and Matthew that scholars call Q, and portions of the gospel of Thomas, the Didache preserves for us a glimpse into a more Jewish-oriented, "non-Pauline" version of the early Jesus movement that I explore in my book Paul and Jesus.