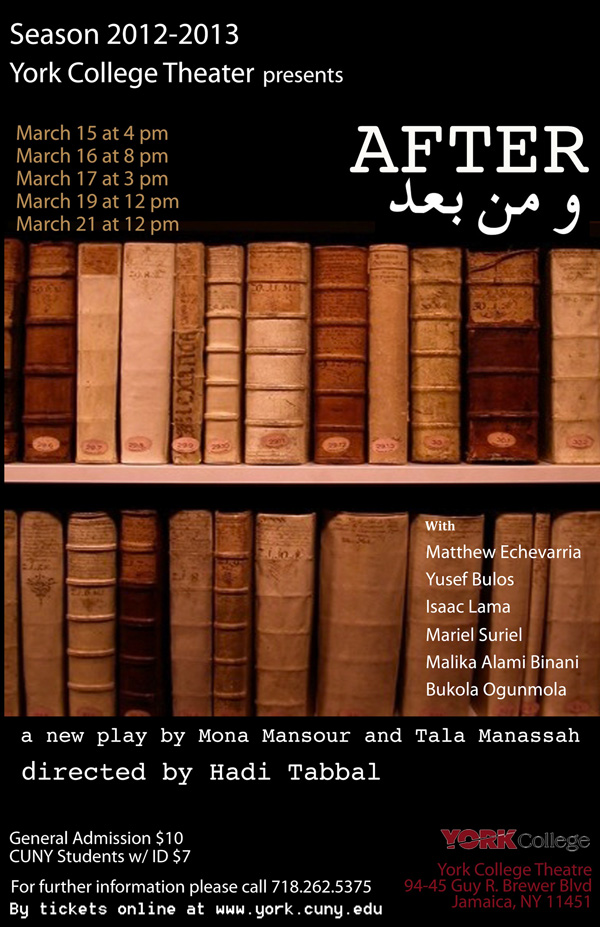

The Sharjah Biennial and Art Dubai are taking place this week and next. Showcasing the quality, relevance, and complexity of Middle Eastern art, it makes sense as well to investigate the achievement of contemporary Middle Eastern theatre. What follows is an interview with Lebanese Director Hadi Tabbal. Mr. Tabbal is directing After, a play which examines the travails of an Arab-American family in New York City, which will open at CUNY (City University of New York) York College on March 15

JS: How did the York College production of After come about?

HT: After submitting my resume to teach at CUNY, three years ago, I was contacted by professor Tom Marion a year and a half later, asking me if I would be interested in directing the spring production of 2013 as adjunct assistant professor. Tom specifically approached me because he was interested, on behalf of the department of performing arts, to produce a play that would involve the Muslim/Arab/Middle Eastern community of Jamaica, Queens, where the campus is. Jamaica is a very diverse part of Queens, NY. It is on the last stop of two, if not, three subway trains, and includes a wide variety of ethnicities. The definition of Arab/Muslim/Middle Eastern was and still is hazy, as anywhere else, but the main incentive was to produce work that would encourage that specific community on campus to be involved: whether in the production or as an audience; basically, to produce a play that pertains to the targeted culture. Being a NY theater artist originally from Lebanon, born and raised in Beirut, and theatrically educated in New York under a Fulbright Scholarship, I believe I was the right candidate. Regardless of my religious affiliations (or the lack of, to be specific), I am familiar with the culture, and indeed, I am.

JS: Why did you ask Tala Manassah and Mona Mansour to write the play? What parameters did you give them? How long did the process take? Will you collaborate again with them?

HT: Last year, in the spring of 2012, I played the lead role of Adham in Mona Mansour's world premiere of The Hour of Feeling at The Humana Festival for New American Plays. This festival is one of the foremost and most competitive festivals in the nation, producing only world premieres. You know, the Middle Eastern theater scene is very tight in New York, where pretty much everyone knows everyone. I had just moved back from NY and I wasn't really immersed in that scene yet. So my agent sends me out on my first audition with that agency, and I book the lead role. No one knew where I came from. And this is how I met Mona. Tala Manassah, on the other hand, I had met through mutual friends through a film connection from Sundance. Tala and Mona, of course, knew each other.

Mona Mansour is an American playwright born in Lebanon. Tala is a Palestinian American educator. Mona and Tala have collaborated before as playwrights. They wrote The House and The Letter, which I saw produced at Golden Thread in San

Francisco, a theater organization dedicated to Middle Eastern Theater on the west coast.

I approached the writers because I did not want to produce a play that has been already done, especially for a project of the sort. There is something not exciting about working on previously produced material if it is contemporary, unless it is a classic whose main raison d'etre is to be reproduced. I wanted something new, because I am interested mostly in directing new work, and because I wanted to give the students the opportunity to be in a world premiere, to orginate roles.

I asked Mona and Tala because they write truthfully about the Middle East and because they are friends I like to work with, and because I knew they would generously give me and the students what we needed. And because Mona and Tala are exactly the kind of writers who are interested in projects of the kind. Because of their interests and cultural backgrounds, their plays have a specific Middle Eastern (or shall I say Arab or Palestinian?) feel. And I was in Mona's play before. I played a Palestinian scholar who flies to London with his newly wed wife to give a lecture on Wordsworth during 1967, during which the 6 day war breaks out, and he is forced to make a very tough decision. Mona's (as well as her writing with Tala) work is full of Arabic (actually Arabic spoken on stage with subtitles), and intellect, and pathos. And I like that. After has all three. The students playing the Jordanian characters (who are Hispanic) speak in Arabic with subtitles on the upstage wall. It really is thrilling for students as well as audiences in Jamaica, Queens.

I gave the writers no parameters other than: 'a play about Middle East/Arab American/maybe Muslim issues'. To be honest, I wasn't even clear about that, but I knew it wouldn't matter. At the end of the day, all this jargon is context and not content. The content will always be universal if the writing is good. That's it. I don't like to interfere with the writing in any way. I consider myself a play developer (if that word exists) and a director, but not a writer in any way. I have an interest in a subject, a context, an issue, or a project of a specific goal, and I communicate that to the writer, I give them more information if they need, and then I wait for a story and a script.

I followed the same process with the other play I am developing called Honey, written by Bekah Brunstetter. I commissioned Bekah to write a play about a Lebanese family in English, that could work for both a Lebanese and American audience. I communicated to her the type of theater I like to do: psychological, visceral, and realistic. I gave her a lot of background on social structure and issues in Lebanon, dramaturgical information, and personal subjects of interest that I would like to talk about in the play, but I was never even interested in being part of what the story is about. The writer sends me the story, and I say: 'I love it.'

The process for After took a solid 6 months. We didn't really have a full play yet by the time rehearsals started. Rewrites continued to happen after rehearsals started (which is typical of new plays), and they continue to happen, thankfully. You are always discovering the best way to do something when you are working on a play that has never been tested before.

I would most definitely keep working with both writers. I think the above provides enough reason to.

JS: What was there about After that made you want to direct it?

HT: To be honest, it is hard to answer this question because the process was not the classical one, where a producer approaches a director with a play, and the director accepts or not. I am not there yet. I was going to direct After whether I like it or not, because it was being generously written for me to direct for CUNY. But the thing is, I knew I was going to like it, and that is why I asked Mona and Tala. Now that I have the play and we are about to open, I can imagine if someone approached me with it. I would say yes. Because it engages the youth, teenage characters, it has a truthful Arab-American voice, it fills a gap in the theater by approaching young audiences of all ethnicities who identify with this family on stage. It is also a great educational endeavor, to produce a world premiere by nationally recognized writers for CUNY students in Queens, New York. Opportunities like this are rare for all of us: teachers, students, audiences.

JS: Have you cast the play yet? How important is it that your actors contribute to the production?

HT: The play was cast in December. I find casting to be one of the most confusing processes of producing a play, most specifically a world premiere, because you know what you are looking for, but then you don't, because you feel every other moment, that you are working on assumptions, but then again, there are no parameters. It really is a tough one: casting. Now add to that casting at a university, where turn out is not necessarily that great. But once I saw the students that I cast, I was sure. I really was. I knew that we had to work on acting skills. I knew that we had to go back to some technical basics at the beginning of the process, but what I mostly knew was that the actors had that human spark, which is what I am most essentially looking for: a spark or humanity, a heart, emotional luggage, a need to express, something moving that is hidden in there, and a kind presence most of all: a kind and pleasant presence in the room. And I see that mostly and I cast based upon that. And of course, there is the technical side of casting the actor who is right for the part (because they look the part and feel the part), but when you don't have eighty actors to choose from, you look for the most essential: the heart.

I taught in Beirut for several years, both college students at Notre Dame University and independent actors at my own workshop at Al Madina Theater. I always auditioned students before accepting them. At first, it might sound presumptuous. Why I am auditioning students in Beirut to take a workshop in acting? It's not Julliard. But that was not the point. The point of the auditions was not to see if they deserve to be in the class, but for me to get the chance to look for that spark: the heart, that emotional echo without which acting has no meaning whatsoever.

When I auditioned Matthew Echevarria, I knew immediately that he was to play Tariq. Same with Mariel Suriel to play his cousin Rania. During the auditions, I made them improvise a scene in Spanish (which is their second language) and the joy and connection that came out of that was really surprising. Malika Alami Binani was called back to play the role of the Mom, which is tough for a young college student to play. And here is the shocker. You could swear she is Tariq's mom, and she is literally his age. Only in college programs this type of casting happens (and usually it is very disappointing), but not this time. Malika also happens to be half Moroccan, so her tongue is familiar a little with Arabic. She says all these Arabic words so believably. Isaac Lama was cast as Joe, the American grad student, and his presence is so pleasant on stage, he is literally what Joe the character is. As for Amelia's role, the young activist, I cast Bukola Ogunmola, who I saw play the lead role in the fall production of the farce A Flea in Her Ear. I was sure of her the minute I saw her. She just does it so well.

What is very special about this production, casting wise, is Yusef Bulos, who plays the grandfather, a pivotal figure in the play. For this one, I did not want to cast a student, because that would be stretching it, and I also wanted the students to have the chance to act with a professional actor, and learn from them. Yusef is outstanding. His broadway, off-broadway, and regional credits are nothing short of spectacular. He has acted and worked with the best in the industry. He is originally Palestinian and fluent in Arabic, and has been acting in New York since the 60s. I did not cast Yusef Bulos. I asked him to join us, and he so generously did. His presence in the rehearsals is a gift to the actors and to myself: to see him work with the words, ask the right questions, inspect the play, and perform is such a pleasure. His relationship to the students and the love between them, the real family feel, is indescribable. If a stranger walks in, they would never be able to tell that this is an established actor in the presence of students. One sees actors together having fun. I almost describe this as an outsider, but I do give myself some of the credit of creating this positive momentum.

JS: How does this production differ from other productions you've directed?

HT: It doesn't differ much on a technical level. All productions pretty much follow the same pattern: script, casting, rehearsals, design, tech rehearsals, dress rehearsals, opening night, run, closing night. What made this production different is the love between the people working on it, between the actors, and between myself and the actors, a feeling of spontaneity that is usually stalled in many productions in the professional world, where the stress of the industry (of the profession) makes the actors and directors relate to each other on a pretty rigid level, which was not the case with After, where no one is doing it as a job so to speak.

JS: Which was the most challenging aspect of this play for you to direct?

HT: Several things. The script changes that accompany a new play. The scheduling nightmares that come with a cast that is juggling their education, their jobs that pay for their education, and rehearsals. Artistically speaking, I guess the biggest challenge lay in understanding some of the material in a playable manner, in a manner that one could translate into exciting behavior on stage. Another thing, which didn't turn out to be much of a challenge actually because of how talented and committed the actors are, was to direct and require from the students certain artistic standards when in fact, in terms of training, they were not necessarily equipped for that. But again, it wasn't a challenge because once I set the level of specificity at which we will be working, the actors just got it. They just did and they flew.

JS: Are there any accommodations you have to make, given the layout of York College's theatre?

HT: The theater actually is a thrust, where there is audience on three sides of the stage, which is tricky when it comes to staging: because there is always some part of the audience that will not see this or that character. And the challenge is this: you don't want to be too concerned about placing the actors on stage for visibility's sake, because then you end up with an artificially staged play and frustrated actors who were not allowed to live in their movements. So achieving this balance of allowing the actors to stage themselves based on their instincts while making sure they are not misplaced on stage can be considered somehow a technical accommodation.

JS: Will the play travel?

HT: No. It won't, but I'm not sure about the life of After after this production. You know, sometimes you do plays and it just feels that they are a one-off gig so to speak. With this one, I feel it has a life thereafter. I can see the play being produced in other schools or interesting theaters who want to engage young audiences. It has that potential.

JS: How did you interpret your mandate to direct a play that deals with Middle Eastern/Muslim-American issues? What's your directorial vision?

HT: With a little bit of irony actually. You know, I left the Middle East because I wanted to do theater in the US. And it is always counter-intuitive, yet so intuitive at the same time, when I see myself (and when the industry sees me most of all) as a Middle Eastern artist, because at the end of the day, I am. The irony is that the family I come from is Lebanese Greek Orthodox, and here I am creating a play about Middle Eastern/Muslim issues. But then again, though the Middle East is the culture I come from, when you do theater, all of that doesn't really matter. Again it's context and not content. The content of a good play is always specific and universal, whatever setting it is placed in. I also take a lot of pride in being hired to direct a play that I am specifically equipped to direct. You can't write what you don't know, and the same thing goes for directing.

I never understood the word vision to be honest. It always seems general. Each play is different, and has a different world that one needs to create. It's really about the connection between the characters and the story that matters. As long as you stick to the essential of truth on stage, you are fine. Vision I think is a result that we see, but is not at all a process -oriented concept.

JS: In terms of set design, who or what will be your visual influences?

HT: The set designer, David T. Jones, created a vibrant one-set bookstore for the characters to live in. The process was simple: to create one set that is simple and efficiently accommodates the action of the play. There is a bookstore in Beirut, on Bliss Street, facing the American Unviersity of Beirut's main gate. It's an old bookstore that survived until recently. It basically had no customers, but it was there, in one of the highest real estate areas in Beirut, and it was blue, very blue. It was basically the bookstore that I kept imagining for the play. Eventually, we painted a lot of our bookstore with the same exact blue. It looks terrific. It's almost like a small homage.

JS: How do you anticipate the reaction to this play, given it content and that it will be staged on a university campus?

HT: York College is very progressive. There are no boundaries for what they produce on stage, no restrictions or taboos. The play deals with ethnicities, racial profiling, generational conflicts, sexual orientation, and family. It might be sensitive for some people, but the community will be very receptive. I guess the Q&A after the shows will tell us.

JS: What advice would you give a student who is considering becoming a theatre director?

HT: I think directing is one of those things that you can't advise for, simply because I believe it is something that comes to you as opposed to something you really aim to do. I understand when someone wants to be an actor or wants to be a writer, but a director? It just happens to you. So you really can't tell someone: "if you want to be a director, you have to do this and that." But then again, once you are a director, I think the best advice is this: Create the world of the play for the actors. Help them understand what they are doing with the words they have to say. And then step back and let them do it. They will do it better than you envisioned.

JS: What kind of experience will audiences have when they come to York College to see After?

HT: A very exciting one because the show is exciting! It is colorful, it has a beautiful repertoire of music, from punk rock to Fairuz, the legendaryLebanese singer. In fact, Fairuz is a huge part of this production. She is mentioned in the play, and the music I included creates the Arab world of the play. Not to mention the emotional impact of her music. The story is exciting because it is about young adults, acted by young adults. It is dangerous and insecure and raw and wonderfully acted. Because I think audiences will identify with the story, they'll enjoy it.