Hmmm... you've got Bernanke saying the U.S. economy is getting better and, as per incoming data, the Fed will at some point slowly start to pull back support. And you've got the OECD doing what all forecasters do these days: marking down their estimates for future growth and warning of various headwinds.

Meanwhile, mixed in with all this near-term analysis, many in my world are mulling over Larry Summers' warning that whatever the cycle is doing, the underlying problem is one of structural slog.

What does it all mean? With the mild caveat that no one knows, I'll take a stab.

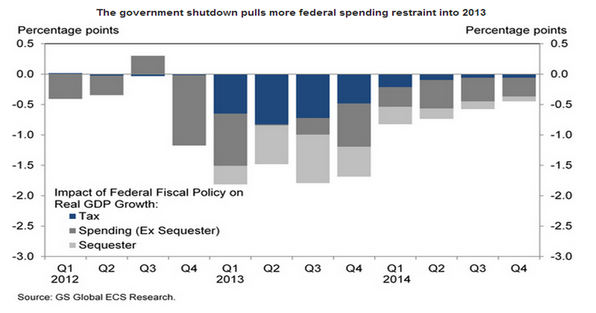

First off, mark me down as pretty skeptical the pace of U.S. growth and jobs is poised to accelerate much. Barring new fiscal break-downs, like the failure to come to some kind of an agreement on the budget that expires mid-January, there will be less fiscal drag in 2014 than this year, and that should add to growth.* But don't mistake less fiscal headwinds for tailwinds. The optimistic view is that lousy, austere fiscal policy is sucking about 1.5 points off of real growth this year and will take 0.5 of a point off of next year's growth (see figure at bottom of post). If true, that's no doubt helpful, but see the above re consistent forecast markdowns.

With an emphasis on the sweeping caveat above, perhaps there's some value in merging the near-term and structural arguments. Yes, economic forecasts are a shaky business, but when they're consistently wrong about the turning point -- i.e., when they're always predicting improvement around the corner just to be marked down once we turn that corner -- you need to look for more structural explanations of what's going wrong.

-Inequality: The fact that less growth is reaching the broad middle class and lower wage workers is a constraint on consumption, which remains 70% of the US economy. During the housing bubble years, (dangerously) cheap credit and the wealth effect from inflated home prices offset this drag, but that's behind us.

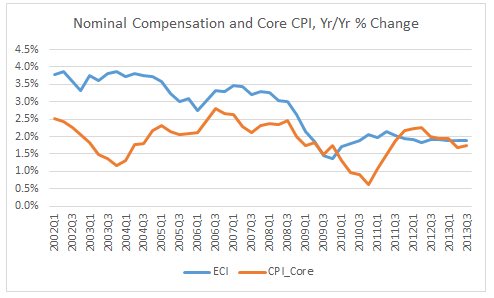

The figure below plots nominal average compensation and the core CPI -- I choose the core because that's what the Fed looks at, but lately it's been running at around the same year/year rate as the overall index. Thus, the figure reveals a) no pressure from wages or prices, and b) flat real compensation growth, and that's at the average, which is pulled up high growth values relative to the median.

Meanwhile, we know that the economy's been growing and that company profits have been high. There's nothing wrong with profits, but there's definitely something wrong when they fail to lead to employment and earnings gains for the broad majority. And remember, I'm using "something wrong" here not in any moral sense (though I'm perfectly comfortable going there) but in terms of pulling out of our growth slog.

Source: BLS

-Weak Investment: Uneven consumer spending along with fiscal drag/austerity and political dysfunction have contributed to a weaker investment climate, not just in the US but in most economies (see slide #9 from theOECD report). You keep hearing about "trillions on the sidelines." Again -- that's also a symptom of high profitability amidst weak demand, along with low inflation. Investors just don't see enough domestic projects with high enough prospective returns to get them back in the biz of investing in structures, equipment, software, at least not at rates that would give us the growth pop we need.

Of course, this begs for a strategy of investment in public goods, but that runs into the austerity buzzsaw.

-Low Inflation: As you see in the figure above, disinflation (falling rates of price growth) is upon the firmament (you can see this more clearly in the monthly data of the core PCE, the Fed's measure of choice). This precludes the lower real interest rates for which Krugman, Summers, and Ball, e.g., have been calling. As I've recently written, it is a strong article of faith among many that a low enough real rate would close the persistent output gaps by triggering more investment and hiring. I'm sure it would help, but a) our Fed is not making sounds commensurate with the pursuit of faster inflation, and b) if there's an investment/growth elasticity to be tapped with cheap money, it hasn't been tapped yet, and money's been cheap, or in wonkier terms, the famous IS curve is looking kind of inelastic to me.

-The Trade Deficit: See here. This isn't a swipe at globalization as much as a swipe at the lack of a competitiveness policy that allows the US to be played by surplus countries that import demand from the US, often through currency management.

There's more, of course, but I've gotta run. There's concern that automation -- the acceleration of labor saving technology -- is playing a role, but the evidence for that is largely anecdotal (Mishel et al say "don't blame the robots"). Many cite immigration, but I don't see that as a slog factor. It's a supply-side thing, and sure, more labor supply can make it harder to achieve full employment when demand is weak, but remember: the last time we hit full employment in the latter 1990s was amidst strong immigrant flows, and of course, those flows been down of late. The slog problem is on the demand side.

Fears of "hysteresis" have also surfaced -- the fear that long-term unemployment, the slog itself, and just the damage of all the austere fiscal policy is itself lowering our potential growth rates.

I've also raised concerns about sectoral misallocation-too many resources flowing to unproductive finance.

More to come on this, as I organize thoughts better than I have above, but let me leave you with a positive thought. If one looked around and saw an economy stuck in low gear like this while investment was robust, public goods were in great shape, inequality was low, kids were accessing all the quality education and child care they needed, climate challenges were being addressed, folks were all adequately housed, and so on, one would be very much stuck for a solution. But that's not our problem. We face many, many unfilled needs, and actually have a robust supply of labor and investment capital ready to go to work meeting said needs.

What's missing is on the demand side. And that can be addressed. The Fed can't do it alone, but policy can definitely help, in ways Dean and I outline in chaps five and six.

*Since I expect sequestration to continue to ply its mindless cuts, the assertion that there will be less fiscal drag in 2014 may seem confusing. But what determines fiscal drag is "negative fiscal impulse:" the increase in cuts one year to the next (see figure below). So the drop off in spending due to sequestration was bigger going from 2012-13 than from 2013-14. Also, tax increases, like the expiration of the payroll tax break, were a much bigger part of the fiscal drag story this year than next.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.