There's an interesting debate going on right now as to factors behind the rise in the inequality of earnings that's been a fixture of our job market for decades (with interesting and germane variations, as you'll see).

At the center of the debate is whether technological change is the main factor driving inequality or is it policy changes that end up steering more income growth towards those at the top of the wage scale. The main protagonists are EPI's Larry Mishel and Heidi Sheirholz with John Schmitt from CEPR on one side, and MIT professor David Autor (who's also had a bunch of co-authors over the years, including Larry Katz and Daron Acemoglu) on the other.

[Full disclosure: I've worked with the members of the EPI team on these issues so am not a dispassionate observer.]

The New York Times magazine nicely summarizes the debate here, but the main points are these:

-If your skills are complementary to the changing technology used in the most productive workplaces, your paycheck will reflect that complementarity. If not, your paycheck will take a hit. It's called skill-biased technological change, or SBTC. Most economists give SBTC a seat at the head of the "what's-causing-inequality" table.

-Larry et al. argue that SBTC is real but it's a steady, ongoing process that doesn't map at all neatlyonto the actual trends in wage inequality. This is particularly true when you look at some interesting, underappreciated nuances of the wage inequality story.

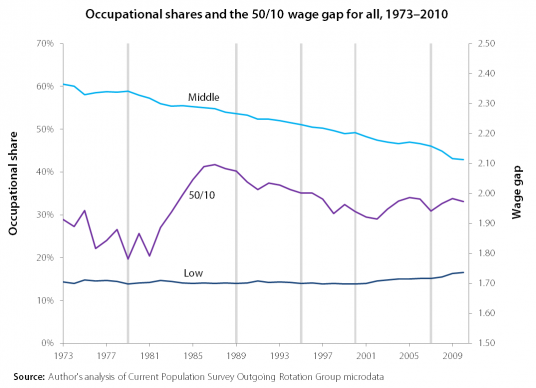

For example, look at the middle line in this graph (ignore the other lines for now). This is the ratio of middle wage (50th percentile) to low wages (10th percentile) and SBTC would predict that it goes up as the skills of middle-wage workers are increasingly more valued in the workplace than those of low-wage workers. And it does rise strongly in the 1980s, but then... it flattens.

Source: EPI

That's inconsistent with SBTC and led many of us to look for better explanations. Autor was among those who came up with a particularly interesting and resonant reason: the impact of technology/computerization on wages isn't "monotonic" (a monotonic impact in this case is one that keeps growing as you go up the wage scale). Instead, computers in the workplace don't hurt low-wage workers (in contrast to standard SBTC theory), kind of hurt middle-wage ones, and greatly complement the work of the highest wage workers.

Under this theory, if your work involves abstract thinking, computers are complementary and you'll benefit from SBTC -- nothing new there. But if your work is repetitive, a computer or robot can probably do it for you -- again, nothing new there, theoretically. But here's Autor's insight: a lot of middle-wage workers have jobs with repetitive tasks and a lot of low wage workers don't. That is, they (low-wage earners) might be home-health aides, classroom assistants, the nice lady who helps me at the dry cleaners. While the production guys who put stuff together can be replaced by robots, the health aide's job is a lot harder to mechanize (or offshore, for that matter).

So Autor explained that the reason middle wages were falling relative to low wages, post 1980s, was because of a hollowing out of middle-wage occupations, while low- and high-wage jobs grew apace.

It's a great theory, and the circumstantial evidence fits for the 1990s. But it hasn't looked right since. As John Schmitt shows -- see the second figure in his blog here -- of the past three decades, the only one where middle-wage jobs were lost and low- and high-wage jobs grew was the 1990s. In fact, in the 2000s, John's figure shows that the share of low-wage jobs grew the quickest while the shares of high and middle wage occupations fell slightly.

In fact -- and now look back at the other lines in the figure above -- according to Larry's data, the low wage share of jobs has been pretty constant, maybe drifting up a bit, while the 50/10 wage ratio jumped sharply in the 1980s and stabilized, and high-wages (not shown) just keep climbing, breaking away from the pack. Meanwhile, mid-level jobs have been drifting down steadily for decades.

So, Autor's SBTC explanation looks limited at best (more detailed work by Mishel et al find little support for it at all). Which raises a few important questions: first, if it's not SBTC, then what is driving wage inequality, and second, does it really matter who's right? Shouldn't we just try to do something about it? Third, what impact does SBTC have on the job market?

On that last question, SBTC plays an essential function: for as long as we've had a labor market, technological advances have been increasing the demand for workers with more education and skills. It's why in normal times, despite the large increase in their supply, the unemployment rates of college-educated workers are frictional (at least in normal times; right now they're elevated). The share of workers with at least a college degree has almost doubled since the late 1980s (from 18.7 percent in 1979 to 33.2 percent in 2011) while that of those with only high-school attainment or less has shrunk sharply. The fact that the job market has handily absorbed so many more workers with so much more education is a critically important consequence of technological change.

On the first question, the reason this argument matters is precisely because the correct diagnosis points us towards the correct policy prescription. If you believe that workers' inadequate skills are the main factor driving the wage gaps, you're going to tout education as the main or even the sole solution to the problem. The thinking goes that technology is increasingly complementary to skills, therefore if more workers get more skills, they'll move from the have-nots side of the equation to the haves' side. (Interestingly, though, this is inconsistent with Autor's thesis, since it posits that labor demand for low-wage workers is stronger than that for middle-wage workers.)

And, in fact, that's exactly where most policymakers are. More education is almost always their primary answer to the inequality problem.

Mishel et al., though staunch defenders of more and better educational opportunities for the have nots, argue otherwise (from the NYT piece):

The change came around 1978, Mishel said, when politicians from both parties began to think of America as a nation of consumers, not of workers. President Jimmy Carter deregulated the airline, trucking and railroad industries in order to help lower consumer prices. Congress chose to ignore organized labor's call for laws strengthening union protections. Ever since, Mishel said, each administration and Congress have made choices -- expanding trade, deregulating finance and weakening welfare [and ignoring the minimum wage and the absence of full employment!!--JB] -- that helped the rich and hurt everyone else. Inequality didn't just happen, Mishel argued. The government created it.

This makes more sense to me than an ongoing (and shape-shifting, in terms of its impact) SBTC story, but the evidence doesn't exactly jump off the page here either. You can definitely show that deunionization, lower minimum wages, and persistently high unemployment rates contributed to the growth of inequality in ways that are more empirically consistent than SBTC. But they only get you part of the way there in terms of explaining the trends.

The fact is that the inequality story is one involving many perps, and a full accounting has yet to unfold.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.