As someone who works with numbers a lot, I find averages to be tremendously helpful. I'd be lost without them.*

But there's one area where averages have been misleadingly used of late, an area where the stakes are extremely high -- this is far from academic. I'm not exaggerating when I tell you that if we don't straighten out this statistical mistake, a lot of people will be a lot worse off.

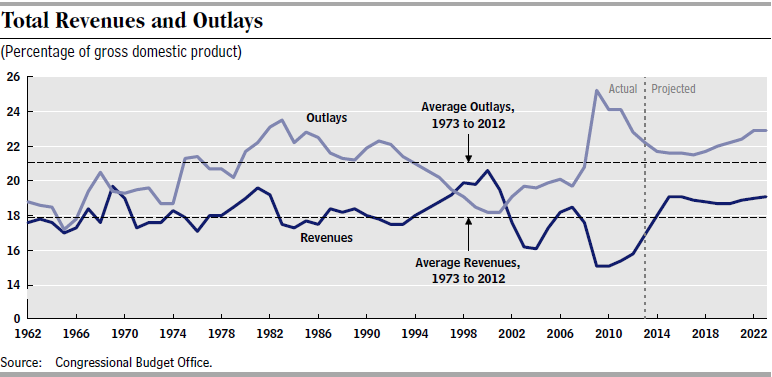

I'm talking about the historical average of revenues and outlays as shares of GDP, as shown in the CBO figure below. The average for revenues is about 18 percent; for outlays, it's about 21 percent. And both lines are expected to climb above these historical averages in the future.

That forecast has led many policy makers on both sides of the aisle to call for a reset: bring both revenues and outlays back down to their long-term averages. While giving testimony to the Senate Budget Committee the other day, I heard this from many of the Republicans (and was thus relieved to get a great question about why it's a bad idea from Sen. Angus King).

The problem with the historical average as a guide toward the future is obvious: there have been fundamental changes in our society and economy that make it an unreliable benchmark going forward.

Demographics, for example. While the share of persons over 65 was relatively constant over the past 40 years at around 10 to 12 percent, it's expected to grow by more than half over the next 25 years (this point and many others that follow were made here by my CBPP colleague Paul Van de Water).

And even though we've recently seen some deceleration in health care spending, the interaction between the demographics that are baked in the cake and faster-than-average growing health costs implies that we'll need to choose one of the following options (or some combination): A) revenue and spending shares above the historical averages, or B) significantly diminished support for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security.

Option C -- continuing today's level of support for retirement security at historical averages for revenues and outlays -- does not exist absent unsustainable deficits. The only fiscally sound way to make due with revenues of 18 percent of GDP going forward would be to make deep cuts to social insurance programs, including higher eligibility ages and significantly lower benefits for economically vulnerable retirees.

Van de Water adds these points:

Federal responsibilities have grown since 2000, with developments at home and abroad pushing spending above the average for earlier decades. These responsibilities include homeland security in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks; aid to veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, many of whom -- especially those disabled in the wars -- will need health care and income support for decades to come; the Medicare prescription drug benefit, which Congress added in 2003; and health reform, which extends health coverage to tens of millions of Americans who would otherwise be uninsured...

Spending for interest on federal debt also will be substantially higher in coming decades than it was during the past 40 years. Today -- largely due to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the large Bush-era tax cuts [80 percent of which were recently made permanent--JB], and the severe recession -- debt held by the public is almost twice as large (as a percentage of GDP) as in 2001, with a commensurate increase in interest costs once interest rates return to typical levels.

Economist Larry Summers makes similar points, adding that our deteriorating public goods will also demand more investment and that we ought not count on productivity gains to save the day:

In some areas technology could greatly reduce government costs but it is important to recognize that by far the largest parts of the federal budget involve cash or in-kind transfers. These parts are far less susceptible to productivity-enhancing technologies than areas that involve the production of goods or services.

Allow me to wax political for a moment before closing this out. There are conservatives who for years have been trying to shrink government particularly by going after social insurance. Most recently, they've used deficit arguments as a rationale for cuts, and they've been extremely successful in dominating the debate.

By advocating that we lock in revenues at or near their historical average of 18 percent, they're trying to lock in option C above: either cut the entitlements way back, disinvest in public goods, struggle to service our debt, or run unsustainable deficits.

In this regard, we should make no mistake: the call for allegiance to historical averages is a call for less government and diminished commitments to current and future generations.

Instead, we need a frank national discussion of the questions embedded in these numbers. Are we willing to devote more of our GDP to these programs going forward? And as long as we're talking straight up about all this, if the answer to that last question is "yes," we can't do so by simply taxing the top 1 or 2 percent.

Either way, the place to start the discussion is by recognizing that as much as we love averages, they don't always point in the right direction.

* Of course, as inequality has gone up so much, the median has become increasingly important as well. In fact, the divergence between the median and the average is a symptom of rising inequality.