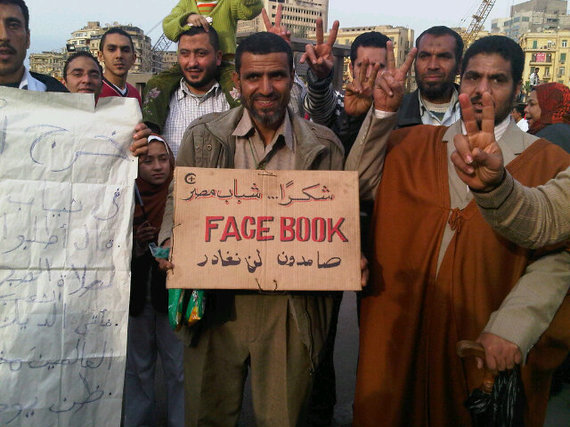

During the Arab Spring, the revolution in Egypt was often described as a Facebook Revolution. On Facebook pages like "We are all Khaled Said," Egyptian civil society organized itself and coordinated its protests in Tahrir Square.

Even today -- four years after the fall of Mubarak, the ensuing political tumult and the reinstalment of the old elite under el-Sissi -- the significance of Facebook for everyday communication continues unabated. And instead of sharing cat photos, Egyptians use the social network for new models of society, fundraising and progressive campaigns.

February 2011 -- Demonstrators in Tahrir Square thank the Egyptian youth and Facebook (via @richardengelnbc)

3,000 friends instead of 300

In Germany, my Facebook contacts have 300 friends on average. Here in Egypt, most people range between 2,000 and 5,000. Facebook is omnipresent; instead of email, I get introduced to new interviewees via Facebook messages, and I am constantly communicating using the platform.

And another difference: while more and more Germans are left disillusioned by the banality of the communication -- all those pictures of food and advertising banners -- many Egyptians are using Facebook to improve their lives.

Even conservative Egyptian foundations like Misr El Kheir -- their profile is perhaps comparable to Save the Children -- has 1.7 million likes on Facebook (the American branch of Save the Children has around 1.2 million likes, with four times the population). And the first thing that the Egyptian organization "Action for Hope" does when it carries out its workshops in Syrian refugee camps is set up a Facebook group for the camp.

Death notices on Facebook

With around 16 million Facebook users, Egypt is ranked number 1 in the whole African and Arabic region. For this reason, more and more companies are cropping up that use this communication power for clever business models, which also have a strong sense of social justice. As is the case with El Wafeyat, a startup that is changing how Egyptians deal with death.

"When someone dies, panic breaks out," explains Yousef el Samaa. "According to Islamic customs, the body has to be buried within 24 hours, and within a few days, an official funeral service must be held. But how are the relatives -- often stricken by grief -- supposed to organize not just the formalities, but also inform all of the relatives, friends and business associates, all within such a short space of time?

El Samaa, a focused young man, is one of the founders of El Wafeyat, a service which places death notices and messages of condolence on the Internet. Previously, Egyptians paid large sums to place their death notices in the big daily paper Al Ahram -- which many people only read to find out if somebody they know has died.

On El Wafayet, relatives can make a free death announcement, and distribute it in real time via Facebook and the other platforms in their extensive networks. At the same time, the company offers a newsletter which aggregates all death notices, and subscribers are quickly informed about current cases. Expressions of sympathy can also be sent online, and Facebook's map function enables funeral guests to arrive at the right funeral hall at the right time.

The organization, which is based on a freemium model, was able to gather investments not just from the Arab world, but was also accepted into the renowned Californian accelerator 500Startups.

The market is big: 500,000 people die every year in Egypt, and by the end of the year, El Samaa wants to reach 1 million users and have a presence in two other Arabic countries.

Facebook for fundraising

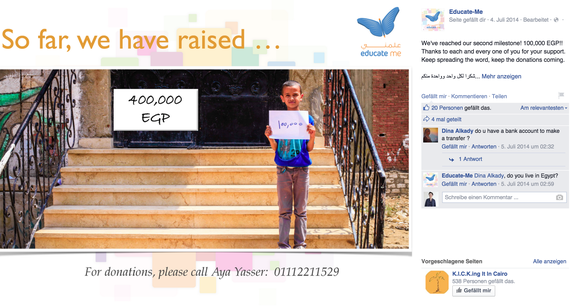

For Yasmin Helal and her NGO Educate Me, Facebook has also proven extremely useful. The 30-year-old played basketball in the national team and worked for a multinational telco before she founded her organization in 2010, which aims to improve education opportunities for children from slum regions.

Right at the outset, she started with a Facebook page, where she not only recruited all 18 full-time employees and 87 volunteer workers, but which also grew to become the most important communication platform for the organization's activities.

The Facebook community is made up of over 75,000 fans, and this strong basis has formed the backbone of a number of successful fundraising activities. "We did crowdfunding without knowing that such a thing existed", says Yasmin, when I meet her in the Sufi Café in the Nile island district of Zamelek. Shortly after founding the NGO, Yasmin posted pictures of 137 needy children on Facebook and found for each one a sponsor to cover their school fees for a whole year.

"Last year, the building that houses our Children's Centre was suddenly put on the market. We were worried about our future, and decided to put up the asking price ourselves -- the whole €46,000.

In June, during the traditional donation month of Ramadan, they made a callout for funding to their Facebook friends under the title "Save our Centre." Interested parties had to ring a telephone number and leave a message with their contribution amount and their address. A pick-up team then criss-crossed Cairo collecting the contributions. Relatively easily reached milestones were celebrated online with great fanfare. The graphics proved to be very popular and were often shared on Facebook.

Two months later they had more than reached their goal, with €58,000 raised. In total, 160 people donated, most of them between 23 and 35 years old.

Educate Me has just managed to repeat this successful campaign: this week over €58,000 came together via Facebook, money which can be used to fund scholarships for children.

The Internet Revolution in Egypt

The organizers of the Facebook page Internet Revolution Egypt were also able to mobilize big numbers of supporters. Formed in order to protest against the high costs of the poor Internet connection in the country, in 2014, over 600,000 Egyptians came together within just a few weeks.

With campaigns like "We'll Pay with Small Change", they crippled the state telecom payment locations, as large number of Egyptians turned up with sacks of coins to pay their bills.

Facebook as safe space

While on pages like "Internet Revolution", playful actionism is the predominant feature, other Facebook Groups are a matter of life and death for their members - e.g. for the LGBT movement, which in Egypt faces criminal prosecution.

As I meet Noor and Azza Sultan in a Cairo café, I'm amazed by the fact that both women have the same surname -- until they explain to me with a laugh that the situation for homosexuals in Egypt is far too dangerous for them to meet with strangers under their real names. Noor and Azza are founding members of Bedayaa, an organization that since 2010 has been working to support people of different sexual orientations, and to protect them from persecution.

Just like the whole LGBT community in Niltal, Bedayaa operates underground - since October 2013 over 150 people have been condemned to sentences of between 2 and 12 years for "procuration" and "sexual deviance." The organization offers courses on internet security - always turn off geolocation on your mobile, never publicly post photos, etc. - and distributes tips that the Berlin NGO "Tactical Tech" has pieced together especially for the LGBT community.

Despite all the risks, the net - and above all Facebook - is for Noor and Azza a comparatively safe space. One of their most important contact points is a private Facebook group, which brings together 500 members - all of whom the administrator knows personally.

They use the group to organize small meetings, but also to inform each other about current arrests. They post warnings about locations where agents provocateurs have been seen, and publish photos of police informers. And if someone is arrested who can't afford legal representation, the group also collects money for a lawyer.

To my question of whether she, like many Germans, is worried about Facebook's data privacy policies, Noor just shakes her head. Like all my Egyptian contacts, they have other problems - and with some of them, Facebook can even help out in tangible ways.

This article is part of the series "lab around the world." You can find more information here.

This post originally appeared on HuffPost Germany and was translated into English.