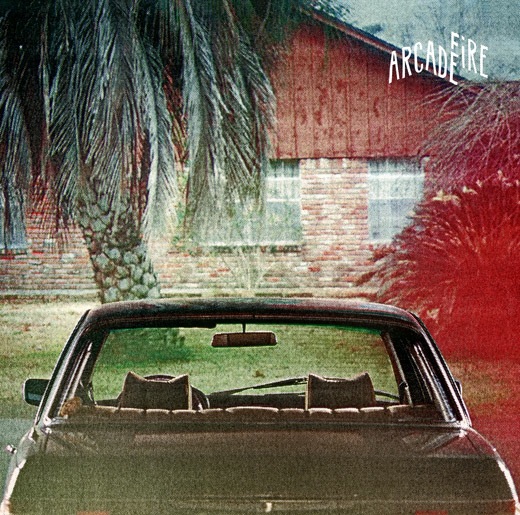

Arcade Fire "The Suburbs" (Merge Records)

On the Arcade Fire's new album, The Suburbs, the "sprawl" is both home and prison. On the one hand, it is all we have known. It is where we grew up; it is where, if we were fortunate, we experienced some childhood joy, spontaneity, freedom and connection even as the inhibiting walls enclosed upon us. As we grow older, however, the "signs" of our imprisonment become more apparent. We are carted off to schools on buses, we become numbered and labeled, we are bombarded with skewed values and false gods. Any resistance or natural expression is labeled "pretentious," and malls--our modern-day temples--stretch out like mountains with "no end in sight."

The effect is both numbing and paralyzing. It is "the death of everything that is wild." The "sprawl" is so encompassing and naturalizing we come to accept it and "just punch the clock." We "move past the feeling" with our "arms folded tight."

This is the overarching "concept" presented in the Arcade Fire's outstanding third album, The Suburbs. Its themes of alienation and estrangement, of course, are not new. They have roots going back at least to the late 18th century when a group of poets known as the Romantics positioned themselves against a social system they felt was soul-deadening and "out of tune." The archetypal Romantic hero was one who experienced this dis-ease, but refused to accept it as natural or inevitable (see Blake, Wordsworth, Shelley and Byron).

Some critics will undoubtedly criticize Arcade Fire for recycling themes (including their own), but the verdict on the band (or the album) shouldn't be weighed against some nebulous idea of "originality"; it should be about execution and effect. And against this criteria, Arcade Fire has created a masterpiece. The Suburbs is no Muse-like expression of juvenile angst and conspiracy ("they will not control us"). It is piercingly honest, complex and often ambivalent, though not in a passive sense (the last thing one could label Arcade Fire is passive). Yet they do recognize that they are part of the culture and system they critique. They don't pretend to be pure and detached. They grew up in the suburbs. Businessmen now drink their blood. The "flashing lights have settled deep in [their] brains."

In "City With No Children" the narrator returns to a Houston suburb depicted as a rich man's abandoned private garden. At first he lashes out: "Never trust a millionaire/ Quoting the sermon on the mount," before acknowledging: "I used to think I was not like them/ But I'm beginning to have my doubts."

In "Modern Man," the narrator sings of waiting in line with the rest of us. He is waiting "in turn" for "a number," but it doesn't "feel right." Nobody seems to understand the point. Waiting for a number is simply a mindless, monotonous show of conformity. "You feel so right," the narrator asks, "but how come you can't sleep at night." Suddenly he feels the urge to "erase the number of the modern man," of wanting to "break the mirror of the modern man."

Throughout the album, this impulse percolates. The Suburbs reflects on the modern condition from a variety of angles and emotions: it is at times nostalgic, at times angry, at times restless, at times uncertain and isolated. Yet mostly they are songs about yearning, about the desire to somehow break through the illusions and trappings of the "sprawl."

In the album's climax, "Sprawl II (Mountains Upon Mountains)," Regine Chassagne sings of being told not to sing. It is a beautiful act of resistance. While the mountains of malls make the world seem like a purposeless maze, she nonetheless refuses to accept a life of cold, unfeeling resignation to the way things are. The city lights alternately beckon as a sign of hope ("they're calling at me, come and find your kind") and condemnation ("they're screaming at us, we don't need your kind").

Her response is both creative and subversive -- and a challenge to a generation fed on seductive bright mirages: "I need the darkness/ Someone please cut the lights."

It is a reversal of traditional notions of illumination. Hope lies in the place most people fear.

The question raised in this song and throughout the album seems to be: If you can't get outside the suburban "sprawl," how do you discover or make meaning inside it? How does one find authentic connection and community in what feels like a prison?

The Arcade Fire's multi-faceted answer lurks in these sixteen dark, but heart-reviving songs. In a way, they can be viewed as passionate letters, waiting to be opened and experienced by a generation that almost forgot such communication was still possible.

For a popular music scene dominated by the likes of Ke$ha and Katy Perry it is a wake up call indeed.

5 Stars/5