Georgia's Senate race, considered the hottest contest in the country, has come down to questions of voter registration, where the Republican Secretary of State is seeking to invalidate thousands registered by a Democratic group after 50 cases that were invalid and another 49 that were deemed suspicious. It's an issue in other contests in North Carolina, Wisconsin, and any state where "Voter ID laws" and politicians control the registration problem and the ability to cast a ballot on Election Day.

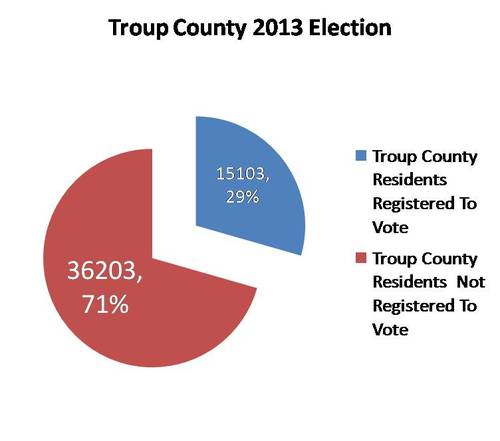

Does my town of LaGrange, Georgia have voting concerns? According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the population of Troup County was 69,053 residents. Of these, one-fourth (25.7 percent) of these people are under the age of 18, and ineligible to vote. But of the remaining 51,306 residents, only 15,103 (29.4 percent) were eligible to vote. And of these residents registered to vote, only 4,682 (31 percent) chose to vote in the 2013 election, according to WRBL, a Columbus News Station. In reality, that's only nine percent of all residents voting in the mayoral and city council elections.

The problem is not a new one. In a 1924 book, authors "Charles E. Merriam and Harold F. Gosnell reported that many persons otherwise eligible to vote had been disenfranchised by Chicago's registration requirements. Their data showed that 'there were three times as many adult citizens who could not vote because they had failed to register as there were registered voters who had failed to vote in the particular election," according to Stanley Kelley, Jr., Richard E. Ayers, and William G. Bowen. Research on registration by Merriam and Gosnell, or the lack thereof by others, was often ignored by scholars until the 1960s.

Scholars often point to the role political parties play in mobilizing people in the election process. "In the United States, political parties make great efforts to get out the vote," writes W. Phillps Shively. "They do not do this to bolster support for the regime, although that is a side effect, but to help themselves win elections." But how effective are these strategies, known as GOTV (Get Out The Vote)? John E. McNulty examined how well GOTV works by examining phone drives in the San Francisco Bay Area in November of 2002 and again in October of 2003. Some of the drives were pro-Democratic, while others were more independent, and another was conducted in conjunction with a prominent local issue. However, "[n]one of the GOTV phone drives with a partisan or quasi-partisan component resulted in a detectable increase in voter turnout. The overall results raise serious questions about the efficacy of GOTV phone drives, particularly those with the intent of affecting electoral outcomes," McNulty writes. In everyday terms, the political biases associated with registering people might be a turnoff, instead of a turnout.

But even nonpartisan calls by phone for people to register are not always effective. In 2005, Gerber and Green looked at field experiments of nonpartisan registration drives by phone before the 1998 and 2002 elections for more than a million potential voters. "The results indicate that this type of phone calling campaign is ineffective," the authors write. Maybe it's not just the partisan tone; it's the dial tone, or absence of one, when trying to use a telephone to get people to the polls.

One might think using new technology, like emails getting people to download and fill out voter registration drives, might do the trick. But that wasn't the case. Bennion and Nickerson found that those who received such GOTV email messages were slightly less likely to vote than those who didn't receive the email, although text reminders to follow-up on emailed voter forms produced some slight improvement.

The solution might come from Liggett et.al.. This research team discovered that health clinics (especially Federally qualified health centers) might be a good idea for getting people registered, as the same people who go to these clinics tend to be overlooked when it comes time to vote. "Volunteers directly engaged with 304 patients," the authors wrote. "Of the 128 patients who were eligible and not currently registered, 114 (89 percent) registered to vote through this project....[s]ixty-five percent of new registrants were aged younger than 40 years," Liggett and her co-authors wrote.

While such health centers seems like a good vehicle for voter registration, it is important to learn from other studies that such drives be non-partisan to be more effective. Additionally, the research reinforces earlier studies that show that a personal contact is key, according to a 2000 study by Gerber and Green. This can apply to more than just health centers. Wherever traditionally under-registered people congregate, this has the potential to do more than reach people in a partisan fashion, or by phone or email. Senior citizen centers, colleges, farmer markets, or state fairs might be additional locations to get people politically engaged, whether they are conservative, moderate or liberal.

John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Ga. He can be reached at jtures@lagrange.edu.