Government doesn't always work as well as it should, but there are solutions. Today, we released new research on the five steps to implementing a pay for success (PFS) project. This is a new concept that can break through traditional barriers to government efficiency to help deliver social programs that produce a public good, government savings, and private profit.

Injecting private capital into the public sector addresses the problem of widespread underfunding of public sector interventions and innovations. PFS, social impact bonds (SIBs), and scaled finance are all similar models that share a core concept: using private capital to buy outcomes, while promising a profit if the program is successful.

Today, government pays for programs regardless of whether they work, and bears all of the risk of that investment. PFS transfers risk from the government to the private sector -- philanthropy, venture capital, or commercial banks. In a PFS deal, government only pays if the program achieves predetermined outcomes.

PFS is a special solution for special problems. This is not a tool for pet projects. It's best suited for programs with a track record of actual success and programs that serve people who use large amounts of public resources and touch multiple systems, like family-based therapies that are designed to work with the most at-risk adolescents and which have the strongest evidence base.

Here's how it works. Each deal requires a collaborative effort: private investors, such as commercial banks, high-net-worth investors, and philanthropists, supply capital; nonprofit service providers supply evidence-based programs; a "knowledge intermediary" interprets the evidence for government and investors; an independent researcher evaluates program outcomes; and the government agrees to repay the investor, plus a profit if the program meets its objectives. If the program does not achieve performance goals, the investors lose all or some of their investment and any potential return.

Governments begin the process by contracting with a knowledge intermediary that manages the process and identifies costly, recurrent social problems and the evidence-based programs to solve them. A financial intermediary negotiates with investors and the government, and the intermediaries ensure that service delivery adheres to an evidence-based model.

The evidence is the key to these deals. If the PFS-funded program has a limited evidence base, the risk of failure may kill the deal before it starts. Investors won't invest if the likelihood of success is uncertain, and governments won't commit to paying a profit on programs that aren't grounded in evidence.

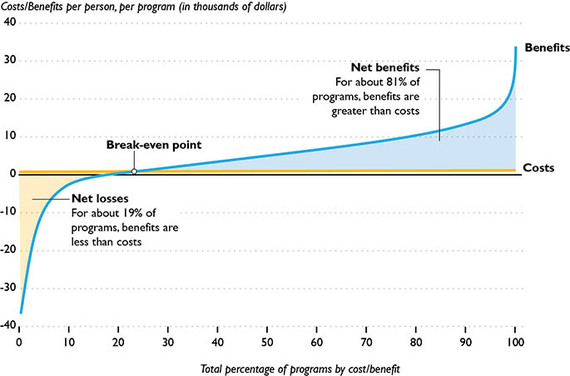

PFS is potentially transformative. It funds solutions to problems that are too big for current funding mechanisms, and shifts risk from the government to the private sector, allowing government to innovate in ways it cannot today. Most importantly, a PFS deal demands data. In order to entice investors, the transaction requires that data is acquired and shared, that target performance metrics are realistic (for investors) and aspirational (for government), and that all costs and benefits are specified. In order for the deal to be properly priced, prior research must be carefully analyzed to provide transparency to all parties, and that data and knowledge must be shared across sectors. No other public financing mechanism places these requirements on government, which is why government is so inefficient today.

PFS is being tested. The challenge for the first generation of PFS and SIBs has been to prove the concept and to demonstrate that a PFS transaction can work. The challenge for the next generation is to jump from funding a single program to funding a portfolio of evidence-based programs. Just as there is no one cause of our most pressing social needs, there is no one solution. The PFS deals and SIBs of the future should support a multifaceted solution to these complex and expensive problems.

Stopping problems before they start sounds like common sense, but efforts to fund preventative programs are stymied by the nine barriers outlined in yesterday's post. PFS financing may break those barriers and offer a new route to positive social change.

Kelly A. Walsh co-authored this post.