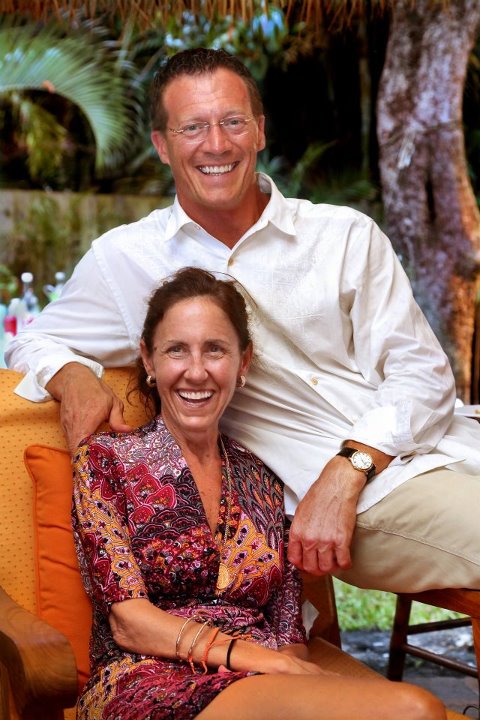

Since the recent release of my wife Susan Spencer-Wendel's memoir, Until I Say Good-Bye, people often say to me, "Your wife is such an inspiration." Or: "This woman changed my outlook on life."

And that classic Rodney Dangerfield line crosses my mind. That's no lady. That's my wife!

When you're married to someone for 21 years, working to raise three children, each holding down full-time jobs, you run the risk of, to quote my wife, becoming like pieces of furniture to each other. We were scratching out a middle class existence -- chasing kids and dollars -- and we were each other's easy chair. Comfortable. Comforting. So accustomed to each other that nothing we did or said was a surprise.

So when Susan was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), known as Lou Gehrig's Disease, at the age of 44, her decisions about how to live and die just seemed natural to me. ALS is a fatal, incurable motor neuron disease that causes its victims' voluntary muscles to gradually weaken until they are paralyzed. The throat muscles and diaphragm also become paralyzed, forcing many patients to resort to a feeding tube and ventilator.

Within an hour of her diagnosis, as she sat in a Burger King parking lot while I (quietly devastated) wolfed down a Whopper inside, Susan's mind was made up. No tube. No vent. No wasted time researching or desperately hunting a cure. She would make the most of whatever time she had left.

"When it's over it's over," she said. "No use complaining about it."

Susan had loved to travel since studying in Europe during her junior year of college. We hadn't been dating long before she infected me with the travel bug. We ended up spending four years abroad together, two in Budapest, Hungary on a Fulbright and another two teaching high school in Bogota, Colombia.

Her wish, for her last year of health, was to take trips with those closest to her. She wanted to make memories for each of us. A cruise with her sister. Sanibel Island with our son Aubrey. Swimming with dolphins for our son Wesley, who has Asperger's and loves animals. A trip to New York, where one morning she watched our 14-year-old daughter Marina try on wedding dresses, a morning Marina has called (on "Inside Edition," no less!) the dumbest thing she's ever done. We'll have to wait, I guess, for her to appreciate that one.

Susan wrote stories about each of these trips. Stories that were in essence love letters to those closest to her.

Several of them were published in our local newspaper, The Palm Beach Post. She had worked there for two decades, with a reputation for being a determined and conscientious reporter. I once heard a reporter from a competing newspaper refer to her as "The SS Wendel." That is the only time I have heard my five foot one inch wife referred to as a battleship, but it is appropriate.

The first piece Susan wrote was about her trip to the Yukon with her best friend Nancy to see the Northern Lights. It was published on Christmas day. The next was about our trip to Budapest for our twentieth anniversary. The responses were wonderful. "Not an ounce of self pity," people said.

Of course not, I thought. It's Susan.

Nobody knew that she'd written the Budapest article on her iPhone, using the Notes app, because she was too weak to depress the keys on a computer or move her fingers across an iPad. They didn't see how each morning I would situate her on the back patio with her phone, and there she would sit for hours, simmering in the Florida sun, tapping away with her right thumb, the only digit she could still move.

Nobody knew that she'd written the Budapest article on her iPhone, using the Notes app, because she was too weak to depress the keys on a computer or move her fingers across an iPad. They didn't see how each morning I would situate her on the back patio with her phone, and there she would sit for hours, simmering in the Florida sun, tapping away with her right thumb, the only digit she could still move.

She never complained.

Then one day I came home to find the patio lined with new teak sofas, chairs, and a coffee table. "What's this?" I asked.

"It's furniture for our chickie hut."

"Our what?"

"Chickie hut. If I'm gonna have to sit and watch my body slowly waste away, then I might as well do it in a nice place. Besides, I already pulled the permits and hired a contractor." She had found a guy who built traditional Miccossukee Indian grass huts, the original housing in the Everglades. I tried to put up a fight, complaining that I liked my wide open back yard and didn't want something from the set of Gilligan's Island plopped in the middle of it, but of course Battleship Wendel won that argument.

Thank God. It was the best idea I never had.

Now, Susan spends most days in her frond covered Shangri-la. It's become a meeting place for friends and well wishers. I have no idea how many bottles of wine have been uncorked out there, even though Susan can no longer drink.

The chickie hut is the place where Susan took the phone call from a literary agent who had read her articles. And the place where she found out her book would be published by HarperCollins. All she had to do was produce an 80,000 word manuscript in four months. On her iPhone. With one thumb.

She delivered ahead of schedule. No surprise to me. "Knowing I could leave you and the kids financially secure was all the motivation I needed," she later told me.

Susan's approach to her plight isn't the typical American response to a terminal diagnosis. She never speaks of "battling" ALS or having a "fight" with Lou Gehrig's Disease. Her approach is more Eastern. Acceptance. Longing for something she can no longer have, she says, causes her pain. Her answer: stop the longing. Spicy foods, swimming, late evening walks, hugging our children and singing them to sleep: they are all things of the past.

So she focuses on what she still can do: smile, laugh, think, feel. She can sit with our new French bulldog, Lenny, on her lap, and if I lift her hand she can pet him. She can let the children hug her, and tell her about their day.

There's one thing Susan has written about me that seems to have a life of its own. We were in Budapest, discussing the fact that, since Susan could no longer move her arms, it took me 20 minutes to get her dressed. "Don't you get tired of it?" she asked me.

"Never," I said. "The least I can do for you is everything."

It was a spontaneous expression of my love. I didn't know she'd put it in a book, or that people would respond to it, and that it's now probably the most famous thing I will ever say.

But how could I have said anything else? My wife has taught me how to live with joy, first in health, then with a terminal disease. Even now, she wakes every morning with a smile, ready for another day. And that makes me smile too.

So sure, Susan may be my comfortable chair, but that just means there's no place in the world I'd rather be.

Also from Huffington Post: