The scriptural readings prescribed this week are largely about special separateness. Specifically, the portion from the Torah and the accompanying selection from the prophet Ezekiel are very much about the Priests and Levites, the clan within the ancient people of Israel set apart for holy service in the sanctuary of God.

Special strictures, rules and regulations apply to this elevated caste - in marriage, in mourning, even in hair style. (e.g. "They shall not make a baldness upon their heads, neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard, nor make any cuttings in their flesh." - Leviticus 21:4)

Not only is this hereditary class granted special access to the precinct of the holy - but, when they do emerge, scripture says, they must take care to leave their holy garb behind, "that they not sanctify the people with their garments." (Ezekiel 44:19)

What could possibly be so bad about ordinary people being "sanctified?"

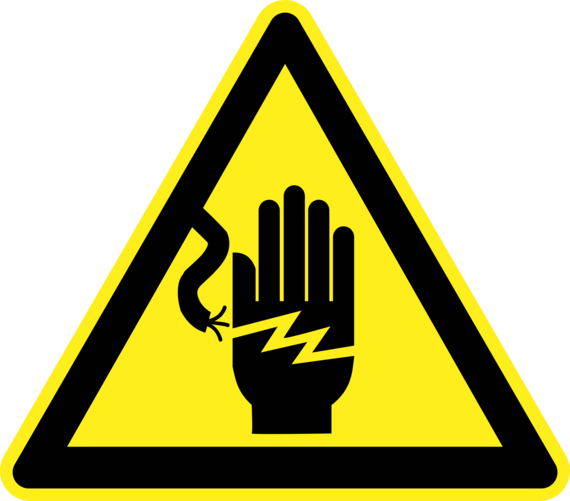

It seems, in the ancient conception, that there is only so much sacredness a person in the workaday world can bear. The sacred, in the scheme of the ancient Temple, is a realm apart, almost as the heavens from the earth. By that reckoning one can understand the expectation that a sacred caste of chosen specialists not zap its nation-at-large with more holiness than can be handled. Sacredness, in this perspective of our Levitical scriptures, is in a way like electricity: those who work in places of high voltage must be particular personnel who take special precautions, and those who do not belong must fear for their lives to trespass.

Let me say quite emphatically that I reject this sensibility with regard to Jewish life on campus and the ways we share it.

In the midst of a variety of practices and origins and aspirations, the sacred must be approachable, and we must recognize that no particular sort of person has exclusive custodianship of the holy. If we think of sacredness as akin to electricity, its light and energy must be associated with signs exactly opposite in message to "DANGER HIGH VOLTAGE DO NOT TRESPASS." Any of us who may have the tendency to consider ourselves specialists in the sacred - and that can happen, by the way, all across a huge spectrum of customs and commitments, not all of them self-defining as 'religious' - have to remind ourselves (and, in this place, I think, cannot help but be reminded) that the radiance and the power of community actually flow from everyone who becomes involved in any way.

From where I sit, I have a breathtaking view of people being uplifted by one another - inspired, informed, activated, moved, filled with wonder, sparked by friction, and most of all - and I hope the word I am about to use will not freak anybody out - loved.

What am I talking about? Well, let me show you what I mean by the view here, and what I see when I speak of the community we have worked to create over these past years, and are working to create. And yes, emphatically, I see the sacred in every image here, in every face in every snapshot of this view: Click here, enjoy - and allow yourself to be electrified!

High Voltage Community

The scriptural readings prescribed this week are largely about special separateness. Specifically, the prescribed portion from the Torah and the accompanying selection from the prophet Ezekiel are very much about the Priests and Levites, the clan within the ancient people of Israel set apart for holy service in the sanctuary of God.

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.