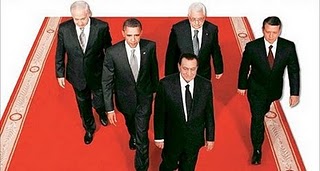

On September 16th, a photograph went viral in Egypt and internationally. It appeared in Egypt's largest and oldest state newspaper, Al-Ahram, and showed Mubarak leading Obama and other leaders during the September Middle East peace talks at the White House.

The only problem is that it never happened; Al-Ahram's editors had photo-shopped the image to show Mubarak out front when in the original photograph Obama was leading the way. Osama Saraya, Al-Ahram's editor-in-chief, defended the doctored photograph as "expressionistic," to reveal the "truth" of Mubarak's dominant role in framing policy toward Palestine.

Parodies of the "expressionistic" blunder quickly sprang up in the Egyptian blogosphere; a popular one shows a young man who has inserted himself into the photograph and flies superhero-like ahead of the all of the leaders; in another photoshop collage Obama is looking at the fake photo, laughing. Wael Khalil, the Egyptian blogger who first pointed out the altered Mubarak photo, said it was a "snapshot" of routine deception in Egypt. "They lie to us all the time," he said. "Instead of addressing the real issues, they just Photoshop it."

Yet when it comes to real suppression of human rights in Egypt, Mubarak is indeed leading Obama. The November 28th parliamentary elections, which resulted in victory for Mubarak's National Democratic Party and at which no international observers were allowed and which were fraught with violence, forging and corruption, are just the most recent case in point. While Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif has described the election as "the best in Egypt's election history," the Independent Coalition for Elections Observation, a group of Egyptian rights organizations, is now calling for Mubarak to dissolve the new parliament.

A few days before the elections, an editorial appositely entitled "Mr. Mubarak vs. Mr. Obama" ran in the Washington Post. It detailed the oppressive pre-election atmosphere in which more than 1000 political activists were abused, opposition media was censored and text messaging was restricted. After the election, the Washington Post published another highly critical editorial, (also aptly titled: "Why is the U.S. afraid of Egypt?") detailing the slow and tepid response from both Obama and the State Department to the election fraud and violence that forcibly allowed Mubarak's party an overwhelming victory. "The Obama administration appears to be thoroughly intimidated by Hosni Mubarak," the Washington Post writes, "when what it ought to be worried about is who or what will succeed him."

Despite their rousing yet merely rhetorical espousal of human rights and democracy, neither President Obama nor Secretary Clinton, the Washington Post rightly points out, have made "any connection between Mr. Mubarak's domestic repression and the more than $1 billion in U.S. aid Egypt receives every year, much of it directed at the military." Obama and Clinton's disregard also ignores the precedent that in 2007, Congress had withheld $200 million of $1.3 billion in military assistance until Egypt made specific improvements in human rights and security in the Gaza strip.

During the almost 30 year period since Emergency Law has been in effect, the United States Agency for International Development has given Egypt $28 billion dollars while the Egyptian military has received $40 billion. Since 2003, Egypt has been the second largest recipient of American military financing after Israel, receiving $1.3 billion dollars in military aid annually. The State Department projects the same amount for 2011.

The Obama administration has consistently spoken in favor of democracy in Egypt, but has done less and less about it. Since coming into office, Obama's administration has cut off funding to any NGO unapproved by the Egyptian government and according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, funding for democracy and governance programs has been cut from $50 million to $20 million. When in May of this year Mubarak's government voted to reinstate Emergency Law, in effect in Egypt since Anwar Sadat's assassination in 1981, the Obama administration responded by calling the government's decision "regrettable."

Emergency Law places "security" cases under the jurisdiction of courts appointed by the president, whose verdicts must be ratified by the president; it allows the president to transfer citizens suspected of terrorism from civilian to military courts; it also allows the government to tap telephones, intercept mail, search individuals and places without warrant, and detain suspects deemed "a threat to national security" indefinitely and without charge.

Despite the law's broad-ranging and repressive power, the State Department responded weakly to its reinstatement, calling it a "disappointment." On June 14th, almost two weeks after the June 6th 2010 killing of Alexandrian Khaled Said, who was dragged from an internet café and beaten to death by two plainclothes policemen in Alexandria under the pretext of Emergency Law, sparking protests across Egypt and internationally, State Department spokesman PJ Crowley expressed "concern" about his death. "We welcome the government's announcement of a full investigation and we urge that it be done transparently," Crowley said, urging "the Egyptian authorities to hold accountable whoever is responsible." The two policemen accused of his beating Said to death, Mahmud Salah Amin and Awad Ismail Suleiman, are still on trial. At least one of the trial sessions, reported Amnesty International, was marred by intimidation by police and security forces. A later trial session, local newspapers reported, included procedural violations of Egyptian law.

These facts in contrast with the idealism of Obama's June 2009 Cairo speech lead some Egyptians to wax nostalgic for the Bush years, when there were tangible improvements. In 2002, the Middle East Partnership Initiative was founded, a $480 million dollar cooperation between the US and universities, NGOs and businesses in 17 countries in the Middle East to enhance as described by the State Department, the "softer" aspects of foreign policy: foreign aid, trade, education and democratization. From 2003-2006, the State Department reviewed the effectiveness of funding in promoting democracy in Egypt. In 2004, Congress passed an amendment to the Foreign Operations Appropriations bill, specifying that the United States could fund Egyptian NGOs without the Egyptian government's approval. And from 2004-2007, aid to Egypt earmarked for democracy and governance increased from $37 million to $86.5 million.

After the 2005 Egyptian parliamentary elections, when the Muslim Brotherhood won 20 per cent of the vote and the 2006 Palestinian elections, when Hamas won a decisive victory, the Bush administration began to reduce the amount of democracy funding to Egypt. Or, as Andrew Albertson and Stephen McInerney wrote in Foreign Policy last year, in 2006 the Bush administration "essentially gave up on democracy in Egypt." Democracy funding seemed contingent on outcomes in line with US foreign policy in the region. When these outcomes, even though achieved democratically, proved different than desired, the Bush administration's commitment to democracy funding waned. The threat of Islamist victories, it seems, was greater than the threat of Mubarak's repressive dictatorship.

Those sentimental about the recent past also seemingly forget or ignore the fact that in 1995 the Clinton administration chose Egypt as its first partner in the covert extraordinary rendition agreement, allowing the United States to use Egypt as a location for torturing and executing CIA prisoners. And it was also, in fact, an Egyptian, Abu Talal al-Qasimi, who was the first extraordinary rendition. He was captured by the CIA in Croatia in 1995 and then flown to Egypt, where he was executed. As reported by Human Rights Watch, his case set precedent for the renditions that would follow throughout the Clinton and Bush administrations. CIA agent Robert Baer summarized the situation: "If you want a serious interrogation, you send a prisoner to Jordan. If you want them to be tortured, you send them to Syria. If you want someone to disappear -- never to see them again -- you send them to Egypt."

There was other substantial "payback" for the funding, most notably the assistance Egypt gave the US during the Iraq War. According to a 2006 report from the US Government Accountability Office to the House Committee on International Relations, Egypt provided "over-flight permission to 36,553 U.S. military aircraft through Egyptian airspace from 2001 to 2005."

These facts indicate that both Clinton and Bush may have used military funding as a serious and potentially nefarious bargaining chip: military aid in exchange for flight permission to carry out a war that some argue had an illegal basis; military aid in exchange for bringing prisoners to Egypt, torturing them and in some case executing them. Egypt, it appears, was used as an American outpost for actions violating international law.

In 2007, journalist Chris Hedges wrote that "The torture practiced in Egypt is the torture we employ for our own ends." While this was true under the both Bush administrations, when the United States was using Egypt for "extraordinary rendition," if we do not ask in 2010 where American military funding to Egypt is now going, Hedges' statement may still apply.

Without clear documentation of how 1.3 billion annual American military funding to Egypt is being used, how is it possible to know that the police forces which killed Khaled Said and the security forces which allegedly subjugated and beat Egyptian citizens during the recent elections are not directly or indirectly receiving military funding from the US government? And how do we know that this same funding had not been funneled into the "extraordinary rendition" program?

The answer is that we do not know, because no comprehensive investigation has been made or, at the very least, has not been made public. But Egypt's consistent and mounting human rights violations indicate that one is essential and urgent.

Human Rights Watch's 2009 country report on Egypt states that "Police and security forces regularly engage in torture and brutality in police stations and detention centers, and at points of arrest" and cites statistics from Egyptian human rights organizations that estimate that between 5,000 and 10,000 Egyptians are held without charge. The report also details the numerous arrests and detainment without charge of journalists, activists and bloggers, pointing to the arrest of blogger Diaa Eddin Gad for criticizing Egyptian policy toward Gaza and the continued imprisonment of bloggers Kareem Amer and Musad Abul Fagr.

Amnesty International's 2009 annual report on Egypt reports that up to 10,000 Egyptians are "administratively" detained, held continuously without charge or trial for years. Administrative detainees, held on the orders of the Interior Minister, are, according to the report, kept in conditions that amount to "cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and some were reported to be ill as a result."

The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights recorded 56 cases of citizens tortured inside police station in 2008-2009, including 13 deaths from torture and 25 cases of arbitrary detention. In 2009, they recorded 5,500 citizen complaints of human rights violations, ranging from ill treatment of prisoners to detention without charge.

Because the information is not publicly available, it's not clear whether or not American military aid is being channeled to the police and security forces which routinely indiscriminately detain and torture Egyptian citizens. Surely, if the United States truly supports democracy and human rights in Egypt, there is nothing to hide in revealing precisely how this funding is being used.

On November 28th, the very day of the Egyptian parliamentary elections, columnist Mona Eltahawy facetiously quipped on Twitter that the most recent WikiLeaks release was a conspiracy to distract the world from the Egyptian elections. But the two events are not unrelated. Whatever one might think about Julian Assange and the documents' release, it shows that WikiLeaks is doing something that the mainstream and independent media are incapable of and unwilling to do. On a smaller but no less courageous scale, Egyptian citizens are documenting the repression of their own government. Much of the reporting of election fraud and violence in Egypt was done by citizens with their cell phones and video cameras, using Twitter and Facebook to share their reports.

It may indeed take a WikiLeaks exposure to uncover exactly how American military funding to Egypt is spent. Perhaps this level of potential "embarrassment" is necessary to pressure Obama and Clinton to pay real attention to precisely where this military money is going and to link its disbursement to improved human rights in Egypt.

Writing in support of the New York Times' decision to publish the diplomatic correspondence given by WikiLeaks to the Guardian, New York Times Public Editor Arthur S. Brisbane asked, "Would you as a reader rather have the information yourself or trust someone else to hang on to it for you?"

Would we as a country rather oversee the military funding to Egypt and investigate its possible use to suppress Egyptian citizens, or would we rather trust the American and Egyptian governments to keep this information for us and keep it secret? While Egypt's state sanctioned truth is often photo-shopped, ours may become increasingly redacted if the choice remains secrecy over transparency and ignorance over information.