"Crap." That word is used quite often by the handful (one handful) of analysts and traders who "shorted" (bet against) the trillion-dollar mortgage-backed securities market that was generating billions in revenues for the world's biggest banks, from 2004 to 2007.

"Crap." That word is used quite often by the handful (one handful) of analysts and traders who "shorted" (bet against) the trillion-dollar mortgage-backed securities market that was generating billions in revenues for the world's biggest banks, from 2004 to 2007.

"Morons." That word is used quite often by the same handful to describe those who had bundled, packaged and re-packaged never-ever-should-have-been-made mortgages (that never-ever-could-be-repaid) into bonds that somehow got rated and sold as riskless; and then re-packaged the crappiest of the "crap" (that couldn't be sold) into still riskier bonds that, absurdly, were blessed as risk-free.

The wonder is that so many supposedly smart and very very highly compensated Wall Street types (no necessary correlation) and their supposedly sophisticated and wealthy investors (no necessary correlation) didn't bother to try to understand the folly of what they were doing. Or didn't care or want to understand.

Michael Lewis: chronicler, explainer, analyst

As an analyst, Michael Lewis (Liar's Poker, Moneyball, The Blind Side) noted that

"Greed on Wall Street was a given - almost an obligation. The problem was the system of incentives that channeled the greed."

As an explainer, Lewis noted that

"The line between gambling and investing is artificial and thin.

The soundest investment has the defining trait of a bet (you losing all of your money in hopes of making a bit more), and the wildest speculation has the salient characteristic of an investment (you might get your money back with interest)."

In reflection, he added, "Maybe the best definition of 'investment' is 'gambling with the odds in your favor.'"

As a chronicler, explainer, and an analyst, Lewis went on to note that "The people on the short side of the subprime mortgage market had gambled with the odds in their favor. The people on the other side - the entire financial system, essentially - had gambled with the odds against them. Up to this point, the story of the big short could not be simpler."

Simpler?

Michael Lewis tries to do the impossible - he tries to explain the investment "instruments" and financial phenomena that the heads of the world's biggest banks didn't understand. No exaggeration, here.

Financial instruments - esoteric and bizarre

Through Lewis's literary repackaging of his research and interviews, the reader is told of teaser rates, floating rates, and interest-only adjustable-rate mortgages ("a home without equity in just a rental with debt").

The reader gets a primer on "no-money-down, no-doc" loans (no verification of income or employment), and high "thin-file" FICO scores; loan-to-value ratios, "silent seconds," negative amortization, delinquency rates, defaults, foreclosures and bankruptcies.

The reader gets a primer on "no-money-down, no-doc" loans (no verification of income or employment), and high "thin-file" FICO scores; loan-to-value ratios, "silent seconds," negative amortization, delinquency rates, defaults, foreclosures and bankruptcies.

The reader is introduced to the esoteric and bizarre: derivatives; credit default swaps (CDSs) on very specific tranches of subprime mortgage bonds and synthetic subprime mortgage-backed collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and CDOs composed of nothing other than CDSs and repackaged tranches of the dodgiest of other CDOs.

The totally unscrupulous "originators" of the subprime mortgages along with the banks that packaged them into bonds were squeezing and selling juice from undeniably rotten oranges - from, so to speak, the rinds and pits.

In startling fashion, the assets (home values) for the asset-backed loans had diminished. Collateral was depreciating dramatically and many borrowers were "one broken refrigerator away from default" on homes that, in some cases, were mortgaged for up to $750,000.

As a justifiably cynical short-seller observed, "There were more morons than crooks, but the crooks were higher up."

Delusion and deceit - and fraud

By complication and obfuscation - aided by delusion, abetted by stupefying or cavalier deceit - big banks and Wall Street firms ignored or hid risk. They ignored what should have clearly been foreseeable, even as they were exposing themselves to the ignorance and misfortunes of millions who were lured into buying homes they could not possibly afford, under the very best of circumstances.

In the film adaptation, the cynical, contemptuous Deutsche Bank bond trader (Ryan Gosling in the role of Jared Vennett; the real-life Gregg Lippmann) uses a Jenga tower of crisscrossing wooden pieces to demonstrate the vulnerability of the bonds packed full with ("securitized" by) subprime mortgages. Payments to investors/ bondholders depended on continuing monthly repayments of mortgage loans by new homeowners who - in any sane view of things - had no wherewithal whatsoever to repay the loans.

In the film adaptation, the cynical, contemptuous Deutsche Bank bond trader (Ryan Gosling in the role of Jared Vennett; the real-life Gregg Lippmann) uses a Jenga tower of crisscrossing wooden pieces to demonstrate the vulnerability of the bonds packed full with ("securitized" by) subprime mortgages. Payments to investors/ bondholders depended on continuing monthly repayments of mortgage loans by new homeowners who - in any sane view of things - had no wherewithal whatsoever to repay the loans.

In the film, the few pieces at the very top of the Jenga tower are labeled (rated) AAA; just below are pieces labeled AA and A. The balance of the tower is hinged on pieces labeled BBB, BB, B, and B minus. By removing the pieces at the very bottom - the bundles of home mortgages mostly likely to default - the entire tower becomes so unsteady that it collapses.

In the film, the few pieces at the very top of the Jenga tower are labeled (rated) AAA; just below are pieces labeled AA and A. The balance of the tower is hinged on pieces labeled BBB, BB, B, and B minus. By removing the pieces at the very bottom - the bundles of home mortgages mostly likely to default - the entire tower becomes so unsteady that it collapses.

Trying to understand what others didn't - or chose not to

That precarious-then-tumbling-tower depiction registered with me, but the pace of the film and the interweaving of Hip Hop noise and Pop culture jumps had me yearning for slow-motion, along with closed captions, subtitles, and pauses for a few well-placed Power Point explanations.

"The filmmakers were showing what 99 percent of the country was occupied with: Pop music, reality TV, celebrity scandals, and the latest tech gadgets. People focus on what's amusing, entertaining, and what's easy to understand. Even the financial regulators were easily distracted, while the rating agencies were being co-opted."

With cultivated forbearance, my 28-year-old son enlightens me. For the past three years, at a West Coast start-up, he'd tried to set up a national online network of hospitals, clinics, and physicians that would offer well-described services with transparent pricing that - I think - somehow ties in to health-savings-accounts and employer-sponsored health plans. For diversion he's a value investor. For stress relief, he shorted the Euro and oil.

With studied patience, he tried to get me to understand what Michael Lewis had unraveled:

"Remember when you were a kid, there were, what, four bowl games to conclude the college football season; all of them on New Year's Day. Right? Something like that.

"Think of those games as the mortgage-backed bonds of the 1980s. Each of those eight teams had high-caliber players. Triple A, in ratings terms.

"Those bowl games were premier events, but money - greed - created demand and now this bowl season there were, what, forty games. Like the mortgage-backed world, there were only so many Triple A teams. I think I read that a fair number of the bowl teams didn't have winning records.

"To stock all the new bowl games, teams with losing records were made eligible. That lowering of eligibility could be thought of as comparable to the lowering of credit standards and thus more and more subprime mortgages were originated, sold, and packaged into bonds.

"Here's the crucial difference: We can look at the match-ups and the stats for the bowl teams. We have relevant information. We can judge whether a particular game might be worth watching.

"But imagine that we had to pay for all forty games in advance, even though we had no idea of the match-ups; that we didn't know which teams were playing, let alone their personnel at key positions. Only the names of the bowl games were given.

"In the subprime game, the bonds were given names that sounded promising but none of the issuers and neither of the rating agencies bothered to investigate the portfolios. Investors bought the package - the repackage, in many instances - but they had no idea what they were buying."

In an effort to try to display my grasp, I tried to follow up with an analogy of my own:

"What if all the college, junior college, high-school, junior-high-school, and Pop Warner football teams in the country were paired up and there were ten thousand bowl games. And, in order to see the top four premier college games, you had to buy a TV package that aired all ten thousand games. Could that be a way of thinking about the subprime mortgage bonds of 2005 to 2007? "

My son suggested that I stay with his bowl-game comparison.

Still, I was not ready to yield the analogy field.

Finance as fantasy

Fantasy football and fantasy basketball are the rage. Millions of sports fans make up their own teams by selecting their favorite players and the players they think will outperform all others on a particular day or weekend.

With little more than the knowledge one might gather from headlines, I imagined that most astute fantasy league participants assembled their fantasy teams by picking the same star players - those who would be rated AAA or at least AA, in bond-rating terms.

I wondered if there might be a temptation to begin to pack fantasy teams with players who, in bond-rating terms, would be rated A and BBB. Or, perhaps, to really really speculate, fantasy teams would roster players who would be rated BB, B, B minus - the NFL players who might be thought of as subprime. If those players just happened to perform reasonably well, wouldn't the payouts be fantastic?

On the chance that there might be fantastic returns, wouldn't there be more and more interest in trying to get a piece of those phenomenal returns - even though the risk would become greater and greater as more and more bets would be placed on fantasy teams that were subprime.

Diplomatically, sort of, my son asked if I had ever played in a fantasy sports league. No, I hadn't. I had to be informed that in every league there was a distinct incentive and advantage to picking top tier players to the extent that the salary cap would allow. Unlike subprime mortgage-backed bonds, every fantasy sports team had Triple AAA and Double AA players. Every fantasy football team would have a Cam Newton, a Carson Palmer, or a Tom Brady.

At the other end of our East Coast - West Coast mobile phone connection, I detected a sigh of exasperation. Then, there was an accommodation, of a sort:

"I suppose at a race track, you might consider the horses with extremely long-shot odds as subprime..." He stopped.

My son's advice: "Go back to the book. Now that you've seen the movie, the book will help you make sense of what you saw and heard."

My son's advice: "Go back to the book. Now that you've seen the movie, the book will help you make sense of what you saw and heard."

I took his advice.

Alchemy by analogy

Michael Lewis helps the reader by offering graspable analogies:

There was alchemy: Again and again, by virtue of clueless rating agencies (Moody's and Standard & Poor's), the financial system's "doomsday machine" transformed and elevated 100 percent lead into an "ore" that was 80 percent gold. Then, insanely, the residual 20 percent would be mixed with slag and other lead remnants - and that, too, magically, would be turned into 80 percent gold.

There was "insurance" which actually amounted to risk-shifting on a galactic scale:

•An investment bank would make a well-informed gamble by selling tens of millions of mortgage-backed bonds to unsuspecting investors, and then turnaround and bet against the very securities the bank had just sold. In other words, a bet against the bet the bank had just advised its customers to make.

•Those few (that handful) who bet against the proliferating aggregations ("pools") of subprime mortgages ("shorted" them) were buying full-value flood and fire insurance on properties that were bound to flood in two or three years, and which had already, essentially, burned to the ground.

Michael Lewis observed that the profits to be devised by the wily and the unscrupulous were made from complicated and opaque bundlings and rebundlings that defied realities; agglomerations that overwhelmed anything that could be derived from honestly dealing with customers. "By leveraging their balance sheets with exotic risks, the psychological foundations of Wall Street had shifted, from trust to blind faith."

Referring to the Federal Reserve's "shocking and unprecedented step of buying bad subprime mortgage bonds directly from the banks," Lewis noted that "by early 2009, the risks and losses associated with more than a trillion dollars' worth of bad investments were transferred from big Wall Street firms to the U. S. taxpayer."

He concluded that the fatal flaw of the system was not that Wall Street firms failed and went under, but that they had been allowed to succeed.

Diagnoses: if greed is good, maybe mania is better

In Michael Lewis's book, the reader comes to appreciate the mania that drove hedge-fund manager Michael Burry (a one-time neurologist) to "short" (bet against) the imperious financial establishment.

In one of a number of his e-mails quoted in the book, Burry reveals how Asperger's seemed to direct his energies - energized his research involvements - and justified his avoidance of personal involvements.

Burry's mania drove him to read, discover, process and discern what others didn't - or couldn't. What he uncovered and fathomed provided him with "a safe place to which he could retreat from a hostile world."

Burry's mania drove him to read, discover, process and discern what others didn't - or couldn't. What he uncovered and fathomed provided him with "a safe place to which he could retreat from a hostile world."

Through psychotherapy and his own innate intelligence, he came to understand why he had "tremendous difficulty integrating himself into the social workings of society, and often felt misunderstood, slighted, and lonely as a result." To escape exclusion and diminishment, he found ways to "build up, reinforce and maintain his ego."

Through psychotherapy and his own innate intelligence, he came to understand why he had "tremendous difficulty integrating himself into the social workings of society, and often felt misunderstood, slighted, and lonely as a result." To escape exclusion and diminishment, he found ways to "build up, reinforce and maintain his ego."

He divined the short - while so many formidable others were long, and totally wrong.

In the film, the portrayal of Michael Burry by Christian Bale does convey a sense of the mania.

Also in the film, Steve Carell portrays the hedge-fund manager Mark Baum (the real-life Steve Eisman) who is the most vocal of the Cassandras. He's the angry one.

The portrayal seems quite true to Michael Lewis's accounts, for Carell's Mark Baum cannot contain his disdain and contempt for imperious Wall Street know-it-alls and supposed guiding-lights such as Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan.

The scenes in which Baum interrupts speeches with unasked-for - cornering, accusing, embarrassing - questions are perhaps the justification for labeling the film a tragic comedy or comedic tragedy. Baum's public challenges are indelicate. His shock of hair bounces from his forehead as if to punctuate his unrestrained righteous wrath. His "shorts" are as much about righting systemic wrongs, as they are about making money.

Like Burry, Carell's character is worthy of psychological, even psychoanalytic, discussion, and respect.

Prognoses - Predictions

Two extremely important recent feature films document "phenomena" that warranted exposure and exposés:

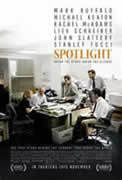

Spotlight (immorality, deceit and vast cover-ups uncovered by diligent investigative reporters) is nominated for the Golden Globe as the best motion picture in the drama category .

Spotlight (immorality, deceit and vast cover-ups uncovered by diligent investigative reporters) is nominated for the Golden Globe as the best motion picture in the drama category .

The Big Short (amorality, fraud, deceit and delusion "challenged" by a handful of contrarian investors) is nominated for the Golden Globe as the best motion picture - comedy or musical.

Both extraordinarily well-made and well-acted films have received Golden Globe nominations for best motion picture screenplay.

Both films have received SAG nominations for outstanding performance by a cast in a motion picture.

I'm betting on The Big Short - buy and hold, I'm going long.

Images from the film, courtesy of Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.