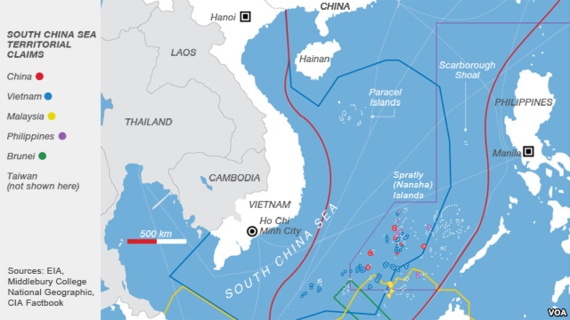

Chinese island building in the South China SeaOn July 12, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague handed down an almost 500-page long decision in which the five-member panel unanimously ruled that China did not have any historic title to its claim over a huge expanse of the South China Sea.

The decision came in response to a case filed by the Philippines in 2013, in accordance with Part XV of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), over the Chinese seizure of the Scarborough Shoal. The shoal was the most recent example of a number of such seizures by China over the last several decades.

The Shoal consists of a series of reefs and rocks, which enclose a roughly triangular shaped lagoon, with a surface area of approximately 54 square miles. The shoal's highest point, South Rock, is less than six feet above the ocean during high tide.

The Shoal is about 120 miles west of the Subic Bay Naval Base, and is well within the Philippine exclusive 200-mile economic zone set out in the UNCLOS treaty. The Shoal is claimed by both China and Taiwan, in addition to the Philippines. Since July 2012, China has barred Philippine fishing boats from entering the Shoal. Manila has accused the Chinese Coast Guard of using water cannons to drive away its fishing boats.

Given its parameters, Scarborough Shoal could be built up into quite a large island. Its proximity to the Subic Bay Naval Base also gives it significant strategic value to Beijing. To date, China has not started any "island building" activities on the Shoal.

A source close to the People's Liberation Army Navy did disclose in April 2016, however, well ahead of the Arbitration Court's ruling, that China was planning to start land reclamation at Huangyan Island, the Chinese name for the Scarborough Shoal, later in the year. In light of the Court's decision, such an action would significantly exacerbate political tensions in the area and might precipitate a military clash between Manila and Beijing.

The Court's ruling had three key provisions. First, it rejected completely China's assertion that it had a claim to the Scarborough Shoal, noting that, "there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the nine-dash line."

Secondly, the court also reaffirmed that the rocks and reefs do not amount to actual islands as defined by the UNCLOS treaty and are not entitled to the 200-mile exclusive economic zone. At best, they would qualify for a 12-mile territorial zone, provided that they were above water for a majority of the time. Under the UNCLOS treaty an "island" is defined as a territory capable of supporting human habitation.

Conflicting land claims in the South China SeaThirdly, the court also found that the Shoal was within the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines and that by interfering with the right of the Philippines to fish or explore for hydrocarbons' in the area, Beijing had violated Manila's sovereign rights.

The court's ruling on the "nine-dash line" has far reaching implications on the various other disputes between China and its neighbors over sovereignty in the South China Sea. Although Chinese fishermen have fished the waters of the South China Sea for centuries, historically China had not extended territorial claims to the region.

That policy publically changed in 2012, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reclassified the South China Sea as a "core national interest." That put the region on the same level as China's claims to Tibet and Taiwan.

Beijing's claim is based on a map published on December 1, 1947, by the government of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. It was, in turn, based on an earlier map from 1935. At the end of WW II there was a land rush by various countries to seize Japanese territories in the South China Sea. The Spratly, Paracel and Pratas islands, that are at the heart of the conflicting land claims, had been controlled by Japan prior to the war.

The original map showed an area demarcated by 11 dashes, which encompassed the bulk of the South China Sea that was being claimed by the Chinese nationalist government. Taiwan is asserting a similar claim, also based on that original 1947 map.

The 11 dashes were later reduced to nine when, at the behest of Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, the region claimed by China in the Gulf of Tonkin was reduced. Later versions of the map added a 10th dash, extending China's claimed sovereignty toward Taiwan and the East China Sea. The reference to the "nine-dash-line," however, was retained.

China's interest in the South China Sea has been driven by a fundamental and far-reaching change in China's economy. Historically, China has been largely self-sufficient. When direct European trade with China began in earnest in the 16th century, European merchants found there was little that they could interest the Chinese in buying. The trade in furs was highly profitable, but it was relatively miniscule when compared with the boatloads of tea, silk and porcelain that China dispatched to Europe.

For much of the 16th through the early 19th centuries, a river of silver flowed from Europe and the Americas to China, where it was exchanged for Chinese goods. It wasn't until British merchants in India discovered that opium produced in the Indian highlands could be very profitably sold in vast quantities in China that the lopsided balance of trade with China began to reverse. In the process they created the first international drug cartel. A cartel that had the advantage of being defended by the Royal Navy, then the world's most powerful.

Today, however, the Chinese economy is heavily dependent on its external trade, both for markets for its manufactured goods and also for essential raw materials. Far from being self-sufficient, Chinese industry now imports vast quantities of raw materials and foodstuffs. It is the world's largest importer of such critical and diverse materials as iron, copper, lead, zinc and soybeans, and the second largest importer of petroleum.

The vast majority of China's commodity imports travel by sea, as do virtually all of its exports. As China's economy has grown and has in turn become ever more dependent on the export of its production and the import of the critical raw materials and foodstuffs needed to run it, China's perceived need to secure and control its maritime approaches has become stronger. Sea power, which historically has not figured prominently in Chinese history, is thus assuming a far more significant role in Beijing's strategic thinking.

China's first aircraft carrier

Over the broad sweep of Chinese history, military threats to China, traditionally, emanated primarily from the west - the Mongol steppes of central Asia and, to a lesser extent, from Indochina. The Japanese land invasion from the east in the 1930s and 40s was, historically, an anomaly. It was not until the arrival of European naval fleets in the 19th century, with their vastly superior firepower, that China began to experience water-borne strategic threats from the east. That naval threat has continued into the 21st century, and has grown ever more important as China's dependence on external trade has continued to grow.

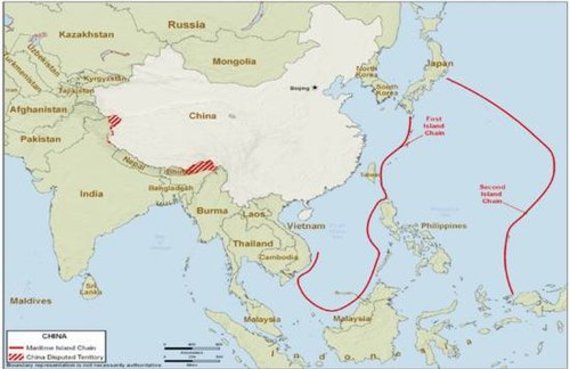

Currently China's defensive doctrine identifies two key geostrategic boundaries: the "first-island-chain" and the "second-island-chain." The first-island-chain encompasses a vast area centered around the South and East China Seas. It begins off the coast of Indochina, curves around Borneo and the western coast of the Philippines, and extends north along the eastern coast of Taiwan, all the way to the southern coast of Japan.

From a naval standpoint, Chinese strategists see this region as "China's backyard." Moreover, it is characterized by a series of "choke points" where hostile naval forces could interdict or blockade Chinese shipping and cripple China's economy. Beijing's claims in the South and East China Seas are designed to make this area a permanent part of China and integrate it militarily into China's defense. Some $6.5 trillion in goods pass through this region yearly.

Beijing claims that its assertion of a strategic interest in the geographic zone comprised of the "first-island-chain" is no different than America's declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. Regardless of the rationale, China's aims, to be successful, would require every one of its neighbors along the South and East China Seas to significantly compromise their claims in the region. It would also force a de facto withdrawal by the US Navy from those countries along the East Asian littoral. It's unlikely that the United States' bilateral defense treaties with those countries would survive such a pullback.

Even more problematic is Beijing's delineation of the "second-island-chain." This zone encompasses the Philippines and Japan, and extends eastward to Palau, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. Significantly in 2015, the PLA Air Force began flights by Chinese H-6k long-range bombers over the Western Pacific, extending to a point about 600 miles west of Guam.

The boundaries of China's first-island-chain and second-island-chain China's ambitions to dominate the sea-air space as far as the second-island-chain may be either wishful thinking or little more than posturing. On the other hand, China's ambitious naval construction program suggests that the strategy is more than empty rhetoric. For the United States to be effectively excluded from this second zone would represent a collapse of American naval power in the Western Pacific not seen since the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

This is not an outcome that Washington will accept. It would represent nothing less than a complete reorientation of the strategic balance of power in East Asia and would have far reaching political and economic implications around the globe. In short, the recent, and unenforceable, Court ruling notwithstanding, the consequences of China's ambition's in the South China Sea are only beginning to be felt and they will reverberate well into the future.