Rachel Hewitt

These days it's hard to claim to be a stranger to corporate sponsorship when everything from the Super Bowl half time show, to the rides at Disney World sport the name of one giant company or another. How does corporate sponsorship fit into the art world where accusations of "selling out" are often tossed around freely? Specifically, how do corporate power players fit into the world of art museums?

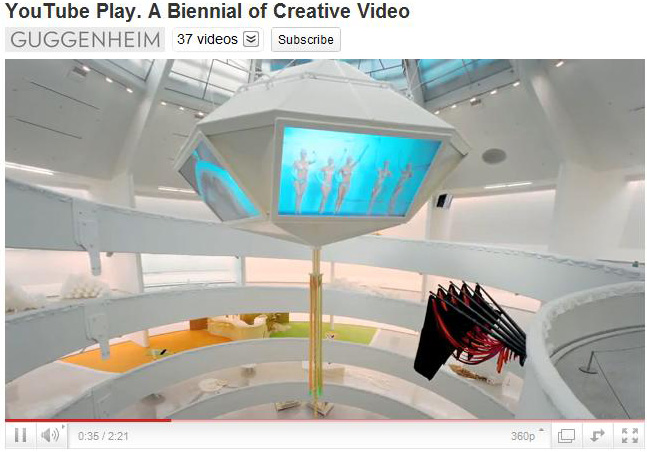

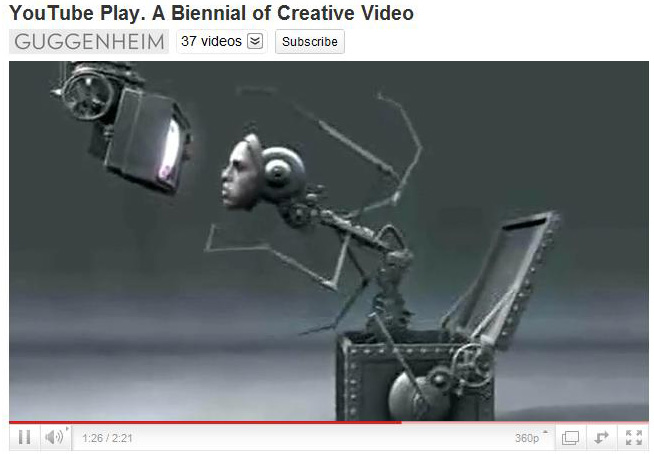

This question arises from recent commotion around the Guggenheim's recent partnership with YouTube (a subsidiary, and essentially a product of Google, Inc.) to present an exhibition called, "YouTube Play. A Biennial of Creative Video," which will open in October, 2010 at the Guggenheim's locations in New York, Bilbao, Venice, and Berlin. Accusations have surfaced that the Guggenheim has become a "pay-for-play" institution, and it's not the first time. The Guggenheim's track record with corporate sponsorship skirts the issue of a conflict of interest, to say the least. Tyler Green does a great job talking about this in his article at Modern Art Notes.

The exhibition in question will showcase "exceptional talent" in online video. Artists were invited to submit video work to be juried by a team of "experts." Part of why this exhibition seems problematic, is that the videos were to be submitted solely via YouTube. Is the exhibition about digital art's impact on the Internet, or of YouTube's? While YouTube may be one of the more ubiquitous sources of online video, are there no other valid outlets for video expression? What about Vimeo whose launch date actually predates YouTube's (albeit by only a few months)? While the exhibition claims to be about the impact of Internet video work, the parameters surrounding the submission and presentation process allow for this to be shown solely through the narrow scope of YouTube.

Compounding this seemingly monopolistic view of online video, is the Guggenheim's response to questions regarding involvement with Google Inc. and its refusal to discuss whether the company has given the museum any money. (Neither Google, nor its subsidiary, YouTube are listed as 2010 corporate donors, however a corporation can be an exhibition sponsor without being a donor/corporate partner.)

This is not to say that museums can't ethically partner with corporations to provide programming. For example, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago has programs for both corporate partnering and corporate sponsorship of exhibitions and programming. The MCA's website lists information on both programs, including benefits to corporations, none of which involve curatorial decision-making. The website also has a downloadable PDF list of corporate donors, broken down by monetary amount of donation for that fiscal year.

The dilemma, then, is not necessarily in museums working with corporations. We all know companies have vast funds, and that non-profits, even major museums, can always use funds. The American Association of Museums highlights the importance of transparency of museums' actions and public accountability in many of their documents, including very specifically in the document "Guidelines for Museums on Developing and Managing Business Support" which outlines interactions between museums and the business sector. This document highlights several very key points where the Guggenheim appears to be lacking. One of the general principles in this document states, "A museum should take reasonable steps to make its actions transparent and understandable to the public, especially where lack of transparency may reasonably lead to an appearance of a conflict of interest." It is the conflict of interest that seems to be a repeated problem for the Guggenheim.

Additionally, any museum-business relationships must be documented, and as such made a matter of record. The AAM document also states that "A museum should respond to all public and media inquiries about its support from business, including allegations of unethical behavior, with a prompt, full, and frank discussion of the issue, the institution's actions, and the rationale for such actions." If nothing else can be said, the Guggenheim appears to be in clear violation of this AAM guideline for public accountability. When asked about this, a spokesman for AAM declined to give an opinion on whether the Guggenheim is in violation, but he did stress the importance of a museum's cultivation of the public trust. This is what he had to say: "The AAM guidelines state our stand on such issues. We are not a regulatory agency and have no powers of enforcement in this area. But museums rely on the public trust, and transparency is always integral to earning and keeping that trust."

As the AAM says, they are not a regulatory body, however, accreditation is key to a major museum's reputation and a museum's relationship with the public is very important in the accreditation and review processes. Maybe the public will never fully get a grasp on the Guggenheim's "collaboration" with Google, but this new addition to the museum's track record of questionable business dealings presents us with questions as to whether these instances will be brought to the table when the Guggenheim's accreditation is reviewed.

From "

From " From "

From " From "

From "