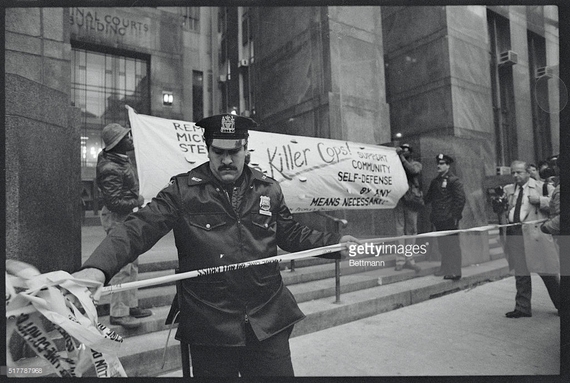

New York Police officer places a cordon around the entrance to the criminal courts building where demonstrators protested the acquittal of six transit police officers in the death of graffiti artist Michael Stewart. (Credit: Getty Images)

Never forget. It's a constant refrain in public discourse. Activists say it. Historians say it. Journalists say it. We all say it. But, we so often do forget. With each passing day, new traumas divert our attention away from the very things and people we vowed never to forget.

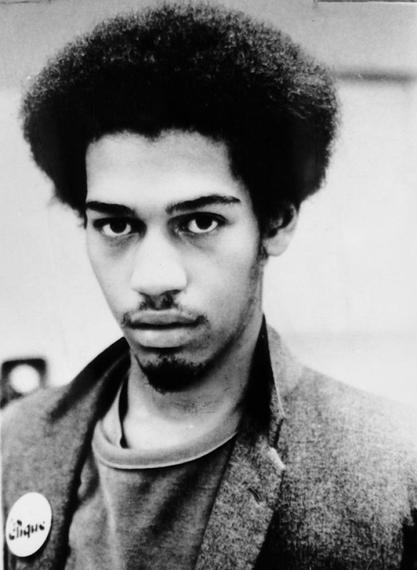

This is the case for Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old African American graffiti artist who died in New York City on September 28, 1983 following a series of events that closely mirror the tragic death of 25-year-old Baltimore resident Freddie Gray. There is no doubt that Michael's memory and his spirit lives on in the hearts of those who knew him intimately; those who conversed with him; those who loved him.

But, more than thirty years after his passing, his name evokes blank stares and even confused looks in public conversations about police violence and brutality. Michael Brown we know. Trayvon Martin we know. Sandra Bland we know. Rekia Boyd we know. Freddie Gray we know. Terence Crutcher we know. These names are painful reminders of the seemingly never ending struggle to stop the unjust police killings of unarmed black people in the United States.

Like Brown, Martin, Bland, Boyd, Gray, and Crutcher--and far too many others--Stewart died as a result of an encounter with the police. The facts simply cannot be disputed: Michael was alive when police officers spotted him spray painting graffiti on a New York City subway around 2:50 in the morning and hours later, he was in a coma. Two weeks later, he was dead. The police officers who arrested Michael that ill-fated morning insisted that the graffiti artist had succumbed to injuries of his own making.

Michael Stewart, 25, an aspiring artist and model, fell into a coma after he was collared by police on Sept. 15, 1983.

Reminiscent of the case of Freddie Gray--who also died after slipping into a coma following an arrest and transport in the back of a police van--the police officers on the scene reported that Michael injured himself as he made repeated attempts to resist arrest. Like the cases of Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner, witnesses on the scene recalled hearing Michael screaming out for aid: "Oh my God, someone help me. What did I do? What did I do?" After officers tied his hands and feet, they carried him into a van and transported him to Bellevue Hospital where he fell into a coma and later passed away.

In the days and weeks following his death, activists across the country were enraged. Here, once again, an unarmed black person was dead following an encounter with the police. At the time, activists drew parallels to other high profile cases in the city including the police shootings of 17-year old Edmund Perry and 66-year old Eleanor Bumpurs. They called attention to the inconsistencies in the officers' narratives and emphasized the physical evidence that revealed a very different story: Michael's badly bruised and battered body including an injured spinal cord, bleeding in his eyes, and swelling on his brain. These were not the kinds of injuries sustained without human involvement, they emphasized, in hopes that someone would listen. In a scene that has since been repeated time and time again, the officers involved were acquitted and Michael's family members were left to pick up the pieces in the wake of his tragic death.

During the 1980s, Michael Stewart was a household name--especially for those living in New York City. People thought often about Michael. They grieved his death and in his memory, continued to demand changes in police practices.

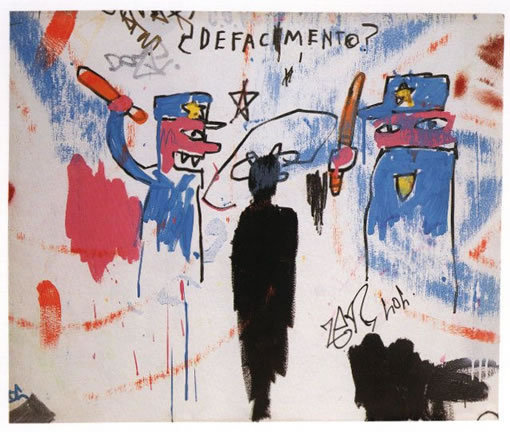

In the immediate aftermath of Michael's death, black politicians, religious leaders and celebrities across the country also evoked Michael's name, insisting that his death should never be forgotten. Deeply shaken by Michael's death, and acknowledging his own vulnerability to state-sanctioned violence, neo-expressionist painter Jean-Michel Basquiat told one journalist: "It could have been me. It could have been me." So moved by Michael's death, Basquiat created a painting in his honor entitled "Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart)."

Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) by Jean-Michel Basquiat

He hoped to not only memorialize Michael's life, but also to bring national attention to police brutality and violence in black communities. He publicly challenged the "War on Graffiti," which criminalized urban graffiti artists and no doubt played a role in Michael's arrest.

In the weeks and months to follow, activists chanted Michael's name. They created posters with Michael's infamous picture--displaying his somber countenance and medium-sized afro--and vowed to fight until justice was served. In 1986, the Michael Stewart Justice Committee--a group created in his memory--organized a candlelight service at a church in Brooklyn to honor those who died on account of police violence and brutality. Michael's parents Millard and Carrie Stewart stood that evening with a crowd of community activists and religious leaders, lighting candles in Michael's memory and in the memory of so many others who had lost their lives in New York City during the 1980s. "We have to build monuments to our loved ones," pastor and activist Rev. Herbert Daughtry told those in attendance. "We have to keep the memory alive," he explained.

That's exactly what well-known filmmaker Spike Lee did in 1989, when he dedicated his film, Do The Right Thing, to Michael and several other New Yorkers who had died in police custody--including Yvonne Smallwood, a 28-year old Bronx woman who died in 1987 while waiting to be arraigned. He wanted to keep their memories alive. He wanted to emphasize the point that their lives mattered and their deaths would not be in vain.

By the 1990s, New York City witnessed a new wave of police violence--not unlike other cities across the country. With each passing year, Michael's name drifted further away from public memory, unfortunately, as new names replaced his own.

More than thirty years later, many are unaware of Michael's story--even as the circumstances surrounding his death are all too familiar. Yet, we must remember Michael--like so many others whose names have gone into historical obscurity. Only then will we remain vigilant in the fight for social justice, never losing sight of the fact that the contemporary challenges we face as a nation are long-standing and enduring. Our resolve to overcome them, and our individual and collective efforts to combat injustice, must be even more resilient.