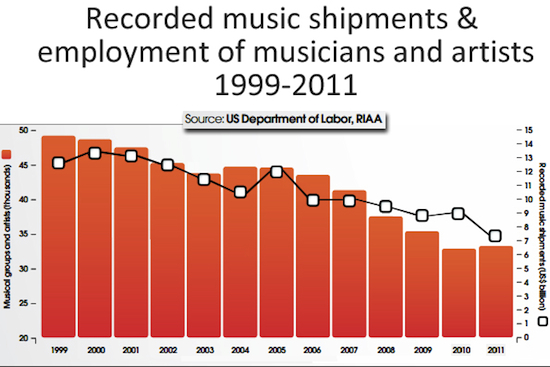

Paul Resnikoff posted this sobering graph at Digital Music News that shows US Department of Labor/Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) statistics from 1999-2011 on music sales and music employment. Needless to say, the picture is not pretty. It seems that despite the RIAA's extraordinary attempts to curb piracy and file sharing (including suing single moms and storming college dorms), the revenue stream from recorded music sales continues in its downward spiral.

The number of "musical groups and artists" shows a similar decline, but let's remember that these statistics are from the Department of Labor, which means that this doesn't include the countless thousands of musicians who are active, but who are not making a great deal of money from their musical activities.

None of this is really news anymore, it's just more data to support what we all know is happening. This has been predicted many times over the years, and it's playing out as predicted--the industry is contracting, while at the same time, as Resnikoff mentions, there is "paradoxically...more music being created than ever before" (a theme that I have also discussed previously).

How will this affect college and university music programs? Music departments in higher education aggressively "recruit" students (borrowing the sports terminology) in order to maintain enrollment and justify their existence. (In fact, the ability to recruit students is one of the primary criteria used in hiring new faculty in the performance area.) The students' parents are, of course, concerned with the employment possibilities that await after spending (or borrowing) somewhere around $50,000 to pay for an undergraduate degree. Twenty years ago, we could point to a number of different career paths that provided gainful employment. The situation today, however, is quite different. Today, when even reliable old stalwarts like law have lost their former lustre, how can we legitimately and honestly encourage students to follow a career path that, for all intents and purposes, doesn't exist anymore?

And what about all of the graduate programs in music or in the arts and humanities in general? These programs are extremely expensive. They are also, at this point, largely providing credentials for college teaching jobs that are more and more difficult to obtain. When the number of undergraduates declines, so must the number of potential graduate students. With these uncontested economic realities in full view, how many will be willing to spend (or borrow) another $50,000 or more to finance graduate degrees that have little or no hope of leading to employment?

The implications for music and the arts and humanities are certainly ominous. In my state of Michigan (as in most states), there are many music programs that are largely undifferentiated in terms of their curriculum and the degrees that they offer. Why should there be 4-5 programs within 75-100 miles of each other that basically do the same thing? How many music programs does each state need? Would half the current number function to both serve community needs and simultaneously raise admission standards?

How should we respond? I think one of the problems lies in the stultifying sameness of so many of our music programs (in particular) across the country. If we want to survive the coming crisis, we need to stop duplicating the programs that exist all around us and build programs that are unique, and that capitalize on the unique attributes of the faculty, the location, the facilities, etc. This may not guarantee success, but it would certainly increase the diversity of offerings, and thereby give students a set of real options from which to choose.

As uncomfortable as these questions can be (especially for those of us in academia), we can be sure that administrators and politicians will be asking these same questions in the coming years as arts and humanities enrollments surely decline along with their graduates' employment and income potential. We should consider new paths and new approaches. To continue with the same strategies, the same ensembles, the same literature, the same curriculum (largely) that worked well 50 years ago is, simply put, folly.