It's a new day in the world of op-ed, and time for yet another commentary on the role of the humanities; the goals of a university; and the pros and cons of the core curriculum. Hopefully, this one will be different.

Flash back to 1968, a time when American cities and campuses were rife with protest, racial rioting, and civil disorder. Simultaneously, a small group of educators were working to create a living laboratory in the problems and promise of the American democracy.

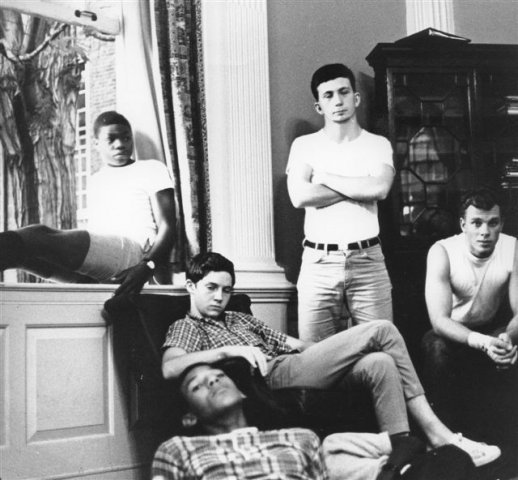

It was called the Yale Summer High School. Created as part of the War on Poverty with a mandate to address issues of social and economic injustice, the school brought underprivileged kids from across the nation to the Yale campus during the 1960s.

Many of our students were alienated from schooling and academic subject matter. They were adolescents, and their focus was less on abstract subject matter and more about personal identity. Many felt academics and intellectual discussion had little to do with where they were at...and with good reason.

As Kenneth Benne, the educational philosopher, once observed, "A person deeply involved in working on the problems of his identity will hardly be able to focus his energies on acquiring the tools, skills, and disciplines of intelligence which intellectual liberation requires." The mission we chose was to turn this around.

A number of the faculty had been teaching in the civil rights movement and had been using what are considered the "Great Books." We thought, "Why not begin there?"

We believed the classics played an important part in the educational process. The primary reason others did not share our enthusiasm had less to do with the works themselves, but the poor manner in which they were often taught -- as interesting relics of sorts, received by students as antiquated pieces of history, divorced from their most basic concerns.

Our job as educators was to make the classics, and the questions they posed, relevant to the times and to the lives of our students. We had faith in our students-- many of them from the inner city-- to take on such an intellectual challenge. The language in which the classics were written often made them difficult to read, but that being the case, students simply had to be schooled in how to read them -- which is why we have teachers.

Creating a relevant curriculum meant developing a coherent framework of study which might aid our students in their struggle for identity. It would have to speak to them and to the times in which we lived, for the alienation of our young simply mirrored the deepening crisis in the country as a whole: the increasing estrangement of its citizenry from each other and from the entity to which they pledged allegiance. It was a crisis not dissimilar to the one facing our nation today.

In 1968, the crisis found expression in the increased tension over race; the continuation of poverty; polarization over the war in Vietnam; the deterioration of our cities; and the widespread use of drugs to "drop out." Like the young, our nation, as a whole, was wracked in pain and actively striving to forge a new self definition.

We believed that any "school" worthy of that designation had to address these questions. Few, however, had chosen to do so. We felt it to be our duty. The times and our students demanded nothing less.

We then asked: "What should be at the center of our curriculum-- its core?" We decided it would be race.

Race had become an issue of increasing concern to society at large. Both the U.S. Riot Commission and the advocates of Black Power saw the root causes of the major schism in our nation resulting not only from the poverty, social inequality and injustice, but from the racism which informed and created those conditions. Our nation, in short, had simply failed to live up to its professed ideals.

We also knew from our experience as teachers that race was very much on the minds of young people. We realized, however, that it interested them not simply as a theoretical issue of sociology and moral philosophy, nor even as a practical matter relating to poverty. It concerned them most deeply because of what it implied about the possibility and/or the desirability of their using contemporary American ideals as grounds for their own identity.

Because the issues surrounding race posed simultaneously and in an immediately apprehensible way all of the value questions relevant to the problem of identity, it was apparent that it would constitute the ideal focus for a core curriculum and facilitate discussion of the contemporary American crisis in the most concrete terms possible.

It was further our conviction that the humanities, rather than any specialized discipline or collection of disciplines, had a unique contribution to make in the investigation and clarification of this issue.

No course in Black History or abstract exhortations to brotherhood and equality could by itself clarify the complex interplay of ideals and actuality, of individual aspiration and social reality, which characterize the contemporary situation. A close and critical reading of humanistic texts might however, help the student to become aware that there existed a plurality of approaches to human problems and that the dogmatic affirmation of abstractions and ideologies could only distort one's perceptions of concrete realities.

And so we read. From Sophocles' Antigone to Marx's Communist Manifesto, Faulkner's Light in August, to Twain's Huckleberry Finn, and several stops betwixt and between, searching together for that which eluded the nation--a working definition of "community"--the shared values that ground people and bind them together.

Through the classes and the daily interactions of one with another, the program generated an authentic conversation on race, as students of different backgrounds came to respect and learn from one another.

I don't know of any other occasion where something as conservative as the "Great Books" approach to education was so effectively applied to something as radical as the Civil Rights movement, the Anti-war movement, and to the personal lives of students.

End of story.

The program was discontinued by Yale, our host university. The University further refused to provide the necessary support for submission of a proposed grant to the National Council on the Humanities to develop a national core curriculum based on our work.

All that visibly remains of the program is a film made 40 + years later, called "Walk Right In" (www.walkrightinthemovie.com) which catalogued that summer's events, followed the students to where they are today, captured their memories of that summer, and recorded its continuing impact on their lives. It has never been screened at Yale, and the work from that summer, for the most part, remains unknown.

So here we are-- almost five decades later. Educators are still talking about a core curriculum, but nothing about its core. A few isolated voices call out for a "national conversation about race," but, for the most part, it goes unheeded. "The true purpose of the University?" has never become a legitimate subject of study in our schools of higher learning. These were all powerful queries when posed in 1968. They remain so today.

A reminder in the words of some of our students in 1968:

To really feel like you're educated you have to have exposure to the humanities. They allow you to actualize yourself as a person.

---- Sam Sutton

Yale taught us that education indeed could be a subversive force. It could be a force of transformation. It could be power. It could open new vistas.

---- Irma McClaurin

Call it brainwashing; call it what you will, I'll call it rewarding and one of the most important experiences in my life. I guess one of the most, or the most significant aspect of the summer was the core course. I really grooved on Hegel, Marx, Plato, and all those other eggheads. No, I really learned an awful lot more from that course, most important of all it made me think, which for me comes next to breathing in importance...

-----Floyd Ballesteros

The YSHS took academic subjects such as literature - it took critical thinking - it took analysis - it took logic - it took philosophy - it took history - and made it relevant to me and to the other kids that were there. I think that's what academics should be.

----- Algeo Casul

____________________________________________________________

Larry Paros is a former high-school math and social-studies teacher. He was at the forefront of educational reform in the 1960s and '70s, during which time he directed a unique project for talented underprivileged students at Yale and created and directed two urban experimental schools, cited by the U.S. Office of Education as "exemplary" and later replicated at more than 125 sites nationwide.