I don't remember how old I was, or if we had already left chilly Minnesota to live in countries oceans away.

All I remember is that it was hot. The kind of heat that chokes you. The kind of heat they should really warn northerners about before they come in contact with it.

The kind of heat that is Laredo, Texas in the summer.

My bare feet pressed against the simmering stone ground as I rounded the corner of my grandmother's house.

"Mi'ja!"

My mother stood behind me, her deep black hair shining in the sun.

"Yes?" I said.

"Oh, nothing, I just wanted to see if you'd turn around."

"Mi'ja" is a contraction of two Spanish words: "Mi" (meaning my) and "hija" (meaning daughter.) Said together, "mi hija" (my daughter) becomes "mi'ja," and is a common slang in the Mexican American culture.

"Oh, hehe," I said, and kept walking.

She'd called out to me in Spanish, just to see if I would answer. She called out in Spanish to see if I placed myself mentally in that culture. I guess I must have enough to turn around, but beyond that I wasn't so sure. And it wasn't the first time I'd wondered.

I don't remember what grade I was in, (why can't I remember? Is this what happens when you get older? Save me, science!) but it was elementary school and we were all on the carpet listening to a man give a presentation about the Mexican culture.

"Is anyone here Mexican-American?" he asked.

"I...am!" I said, raising my hand.

"What's your last name?"

Uh oh.

"....Hibbard," I said, feebly.

"That's not a Hispanic last name," he said, and turned back to the white board.

My cheeks seared red-hot, as I retreated...too embarrassed to say "my mother's maiden name is Barraza" in defense.

I did not have my mother's name. Did that mean I didn't have her culture?

The question wasn't one that plagued me in my youth. If it had perhaps, I would have figured out the answer sooner.

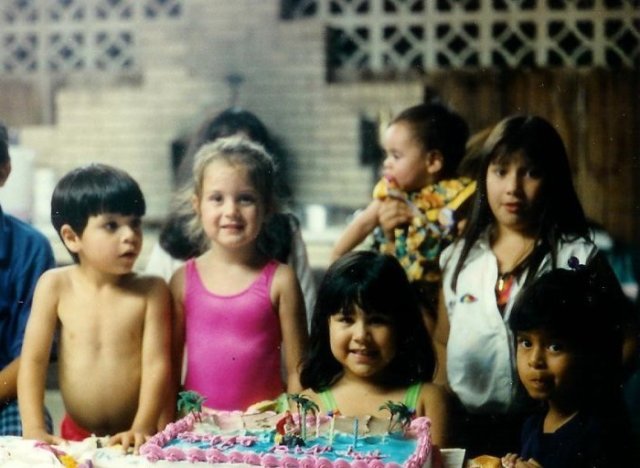

(Me, age 4, in Laredo, TX with my cousins)

Last year, President Obama braved the lions den when he was interviewed by the ladies on The View.

He talked about everything from Lindsay Lohan's jail stint, to Snookie running for mayor of Wasilla (not kidding.) More importantly to me, however, were his comments, though brief, on being multicultural.

"I can be African American, I can be multiracial, I can be..you name it," he said.

"What matters is am I showing people respect."

My teenage identity crisis was a little more complicated than the typical phase. Not long after the classroom incident, my family and I moved to London for my father's job. Shortly after, we moved to Tokyo, where I carried out the rest of my pre-college schooling.

The question now wasn't just am I a "latina," it was also "what does it mean to be American? Am I British? Japanese?"

Thanks, parents. (Only joking, I probably just think too much.)

Believe it or not though, the distance brought clarity ...at least to the first question. Going back to the states for the summers meant we cramped all of our family visits into a very short amount of time, and it was always a very quick transition. The vivid, fast, juxtaposition of my family's two ethnicities made the important parts stand out. Once they stood out, I remembered them. Once I remembered them, they were a part of me.

It was like a machine gun of cultural experiences.

One minute I was riding the train to school in Tokyo, the next ... BAM! homemade tortillas at abuelas house, surrounded by so many cousins, tios, tias, and niños that there aren't enough places to sit. (Fun fact: my mother has exactly 60 first cousins. And you think your family is huge.)

BAM!

Pictures of the John Paul II, Jesus, or Mother Mary around every corner.

BAM!

Trying desperately to remember the Rosary in Spanish while wondering if my bisabuelita should really be kneeling on the hard ground for that long.

BAM!

Smashing maiz generously on a corn husk.

BAM!

The clacking of tiles in the loteria gourd.

But most importantly: the words mamacita.

Mamacita, my grandmother calls me warmly while moving around the kitchen.

Love you, mamacita, my grandfather says as he hugs me after work.

Being Mexican to me meant being someone's mamacita, and as long as I was that, what else really mattered?

So what if my last name isn't Barraza?

So what if my mother's deep skin and black hair was watered down by my father's blondish locks and pale palor?

I have my mother's eyes, her culture's language, and most importantly, I have the term of endearment that means I am loved.

And being loved means you belong.

Recently I tweeted back and forth with a friend from Tokyo who faces the same questions, though for her it's between the Japanese and American cultures. She articulated what I had been struggling to put into words: being a part of two cultures means it's difficult to fully be a part of either.

My experience echoes hers. When you have both, identifying fully with one means disowning the other, and frankly, that sucks. It also used to frustrate me a lot ...until I heard the "mamacita."

Until Barack Obama said it doesn't matter who or what he is as long as there is respect.

Until Dr. Otto Santa Ana wrote this in an article for PBS's American Family, entitled "Is There Such A Thing As Latino Identity?"

"Identity is only a problem, a big deal, if we continue to think about identity in the current commonplace way that each person is just an individual, born a unique self from infancy, who grows up but does not really change much in his or her life.

Our identity changes across time. Our identities as human beings are fluid, not a fixed thing.

We all have multiple identities, rather than just one. Consider identities to be multiple facets on the precious gem of our individuality. Or to use another metaphor, each of us is a constellation, a cluster of related (or even unrelated) identities that correspond to the wide-ranging roles through which we live our lives, and settings in which we live our lives."

No one (not even someone from only one ethnic background, like my mother) is ever just one thing, therefore everyone, at least to a certain extent, has to pick and choose the stars in their constellation.

When I am grinding tomatoes to make salsa, I am my grandmother's Mexican mamacita.

When I am standing at the top of a fjord in Norway with my father's mother, I feel the nordic heritage stir some sort of inherent spirit.

I am both, I am neither, and I belong.

After years of feeling I had to choose to either be Mexican or Scandinavian-American, it turns out, Christmas krumkake can actually go really well with tamales.

Seriously, you should try it.