If you read my recent Huff posting, Breast Cancer Sucks and You Could Die From It, then you already know that I have a very special aversion to October, more commonly known these days as "Breast Cancer Awareness Month". And you also know that what bothers me isn't the widespread attention the media brings to bear on breast cancer, but the nature of the attention.

You see, it seems to me that in order to free women from what might be paralyzing fear of the disease (fear which might hold women back from seeking out early detection and medical intervention), the media has "pinkified" breast cancer, dressing it in stiletto heels and handing it a Cosmopolitan. I am all for focusing the attention of the public on breast cancer as a treatable disease, but I find myself becoming impatient and annoyed by Breast Cancer Awareness Month because of the way it has come to make the disease seem practically friendly and approachable, as opposed to the sinister and potentially deadly disease that it actually is.

It wasn't always this way for me. Before I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2002, I used to hate Breast Cancer Awareness Month for another reason entirely.

That reason was crazy, irrational (although, ultimately, not unfounded) fear.

October would arrive in full pink regalia, with the local news and all of the chick-mags on the newsstands having something to say about breast cancer: inspiring stories of young survival, heartbreaking stories of lives cut short, pseudo-medical stories listing the 10 ways to lower breast cancer risk. I felt bombarded. I felt ambushed. I felt ill at ease. And I felt guilty for feeling those feelings.

And so, each October, I tended to avoid the news and to hand over my Glamour and Self magazines to my sister. And despite that I was an avid Central Park runner at the time, I chose to do my running on the East River whenever there was a risk of running straight into the throngs of pink visors and pink t-shirts bearing messages of hope for women fighting the disease, or listing the names of those who had fallen in battle. Each year, I would sign up for the Susan B. Komen Race for the Cure, even throw in an extra hundred bucks donation (as if throwing a Benjamin at the disease would keep it from finding me). But then the day of the race would arrive, and suddenly I would find some reason why I couldn't make it to the Park that day.

But surely, I wasn't afraid of breast cancer, right? Because what was there to be afraid of? Breast cancer wasn't something that could happen to me. No. Not me. Never.

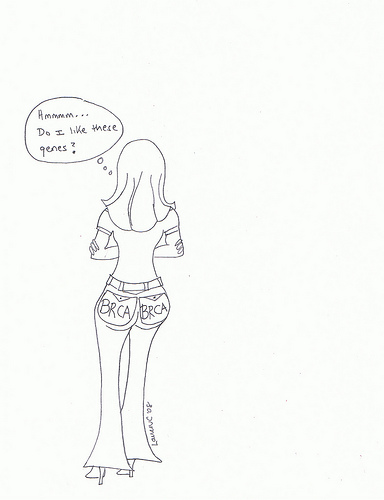

I mean, hell, despite that there was an appallingly high number of people who had died young from cancer in my family, my then-OB/GYN told me that breast cancer is inherited through the mother's side alone, pointing out out that all of the cancer in my family was on my father's side. Never mind that my mother is an only child. Never mind that the only women in my father's family were his mother and his aunt, and both of them had died of breast cancer. And never mind that my father was a young prostate cancer survivor, and that prostate cancer is in the same family of cancers as breast cancer. Never mind all of that, according to Dr. B, who thought it a waste of time and money for me to get tested for the breast cancer gene (or, more accurately, "genes" and commonly referred to as the (BRCA genes"). And so, like the obedient little patient that I was, and not without an unsettling level of unease, I put aside the notion of testing for the BRCA genes and went back to staying home as much as possible during the month of October.

Not long after, in 2002, I found a lump. I was only 36 years old, and I had read somewhere that 80 percent of all breast tumors turn out to be benign, but as soon as my fingers touched the hard, angular mass in my right breast, I knew it was cancer. And it was. And I remembered the BRCA testing that I hadn't had. And there was some anger at Dr. B. And at myself for not being more assertive with her.

I took that anger and I channeled it into action. Without even bothering to have the BRCA test, I demanded that my breasts be removed, post haste. My theory was that if my breast had betrayed me, then I no longer wanted it hanging around (literally). And if one breast betrayed me, then why wouldn't the other? Off with their heads. I was cavalier about it, yes. But that helped me to be brave. And my breast surgeon seemed happy to comply. And no doctor I have ever met has ever questioned my decision.

Nevertheless, my doctors did suggest that I have the BRCA testing. Not to determine a course of action for my treatment, but to offer my sister a clue as to her breast cancer risk. Notwithstanding what Dr. B had told me just a year earlier, it turned out that everyone on my case was certain that with my family history, surely I would test positive. And in that case, my family would forever have valuable information about their cancer risk. Especially my sister. If I tested positive, then V could be tested for the same gene. If she then tested positive, she could opt for a double mastectomy if she wanted to reduce her risk of getting breast cancer down from 85% to less than 10%. Or she could participate in "watchful waiting". But either way, V would be armed with knowledge. If I didn't take the test, or if I took it but did not turn out to have either of the BRCA genes, then V would have nothing for which to test.

And that is exactly what came to pass. That I didn't possess either of the BRCA genes, that is. My genetics counselor and I were so shocked by this result that we had the tests run a second time.

Still negative.

And so, it turned out, there was no gene to explain any of the cancer in my family. At least none that science has yet identified. And since you can't test for what you can't identify, I am left to ponder what it is that (coincidentally?) led to my grandmother's death from breast cancer at age 59, my uncle's death from colon cancer at age 39, his daughter's diagnosis with lymphatic cancer at age 24 (she survived), my father's diagnosis of prostate cancer in his 50's and lung cancer in his 60's (three years later, he is going strong). And I am left to wonder whether my two sons will face early diagnoses of cancer, themselves, and what we can do to prevent it, or at least catch it early, whatever "it" is. And my sister is left to wonder whether she has whatever my dad and I have been having, or whether she is enjoying the benefit of genes from my mom's side of the family.

To know what your risk is, I consider that a gift. One which I wish I could give to my sister, my kids and their kids and so on. October is not only Breast Cancer Awareness Month, but it is the month in which my sister's birthday falls. Some Octobers now, I fantasize that on my sister's birthday, I could hand her a box wrapped in shiny (okay, pink) paper and ribbons, and in the box would be a certificate proudly proclaiming, "Congratulations! Your sister has tested positive for the BRCA gene! Now go on, girl! Take this info and go get tested too! Find out if you too have an 85 percent chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer, or if you have the same risk that most other women face, which isn't so bad really at all!

Unfortunately, I can't give V that gift. But how I wish I could.