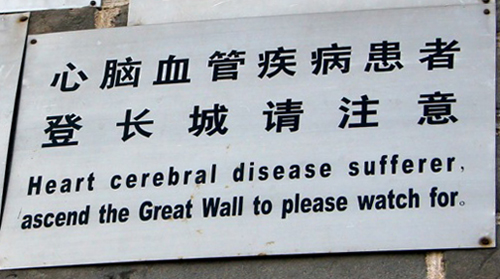

Signage on China's Great Wall doesn't always get across a clear message. Photo by Leo Stutzin

Ridiculous translations provide the simplest and funniest comic gambits in David Henry Hwang's Chinglish, which generated roar after roar of hilarity when it opened Berkeley Rep's season in the Roda Theater a few days ago. As is obvious in the photo above, which I took on the Great Wall near Beijing last October, even sincere efforts to communicate simple concepts don't always bridge linguistic divides. The results, very often, are giggles rather than enlightenment.

But confusion and consternation stemming from flawed translations provide only a small portion of the comedy and drama shaped by Chinglish. Hwang's bigger quarry is the difficulty cultures face in struggling to understand each other, even when the spoken words are clear and the goals are similar.

When the cultures, values and languages are as different as those of China and the USA, the barriers can be as massive as the Great Wall, at least until some way is found to discover common ground.

In Chinglish, the major goals involve money, power and romance. None is achieved by following a direct line.

Michelle Krusiec, Alex Moggridge and Brian Nishii: Even in English, conflicts arise. Photo courtesy of kevinberne.com

Hwang's protagonist is an American businessman who runs a Cleveland-based sign-making company that has seen better days. In hopes of tapping into the huge market that so many western firms covet, he travels to China with a seemingly simple objective: to create and fabricate English-language signs that won't embarrass his clients. A secondary motive for his trip is more personal: to escape the notoriety he achieved as a major player in the Enron scandal.

But signmaker Daniel Cavanaugh (Alex Moggridge, a perfect embodiment of mid-American sincerity, innocence and opportunism) learns very quickly that deal-making in China requires more than the presentation of proposals and inking of contracts. It demands strong relationships with important people, cultivated over time. Who you know matters more than what you know, even in Asia.

To some degree, Cavanaugh understood this even before he arrived, so he hired a consultant, a British expat named Peter (Brian Nishii) who had lived in China for many years, spoke Mandarin fluently and knew the right people. In this case, the "right people" are commu-capitalists with powerful positions in the inseparable spheres of politics and business.

The dynamics of deal-making and the impediments to communication become clear early on, in a meeting between Cavanaugh, Peter and two party officials, Minister Cai (Larry Lei Zhang) and Vice Minister Xi (Michelle Krusiec). A fifth participant at the gathering is a young translator, Miss Qian (Celeste Den) whose English is less than perfect.

About one third of the dialogue is spoken in Mandarin, with succinct translations projected above the stage. The mistakes are easy targets. (Daniel: "We're a small family firm;" Qian, projected: "His company is tiny and insignificant.")

The flub brought down the house, as did similar bloopers by different translators at later business meetings.

But the goal of the session -- to build the beginnings of trust and friendship between Cavanaugh and Cai -- succeeds, even though the bond stems in large part from still another quirky misunderstanding: the minister's affection for Chicago, which comes up in conversation.

Hwang's depiction of business takes a course that shouldn't surprise anyone who follows news out of China, even casually. Cavanaugh and Peter, as his surrogate, find themselves confronting nepotism, local politics and impenetrable relationships, imperiling the hopes of both the foreigners and locals. Sometimes they score, sometimes they don't.

Xi (Michelle Krusiec) and Daniel (Alex Moggridge): Business can get personal in Chinglish. Photo courtesy of kevinberne.com

But business takes a bizarre turn as Cavanaugh and Vice Minister Xi discover that they have more in common than concerns over signage. Xi, whose English is far from fluent but much better than that of the official translators, makes the first move in a chain of events that lead hesitantly to trust, affection and sex.

Their efforts to understand and connect with each other ring notes of hilarity, poignancy and pain that are as credible as they are theatrically effective.

Directed by Leigh Silverman, who staged Chinglish in Chicago and then on Broadway, and performed by a uniformly skillful cast, the production moves with sparkle and wit from start to finish. The fluid pace receives a tremendous boost from David Korins' ingenious set, which metamorphoses in seconds from office to restaurant to bedroom and other venues through the intricate linkage of two revolving platforms.

The show was staged jointly by Berkeley Rep and South Coast Rep, and will travel to Hong Kong after a run in Costa Mesa.

Chinglish runs through Oct. 7 in Berkeley Rep's Roda Theatre, 2015 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $14.50-$99 (subject to change), from 510-647-3949 or www.berkeleyrep.org