"I have never seen a day of peace in my life," Colombian civil society leaders have told me. As President Juan Manuel Santos visits Washington on February 3 and 4, 2016, there's hope they may see such a day.

Talks with the FARC guerrillas are advancing, with agreement on the thorniest issue, transitional justice, reached in December. In January, both parties called on the United Nations to provide an unarmed mission to verify a bilateral ceasefire and the laying down of arms, another signal that an accord could be signed soon.

Sixty diverse victims of the conflict have had a chance to speak to the peace table in Havana. They have supported peace, called for the truth to be revealed and demanded guarantees that the brutal past will never be repeated. Women's groups fought for and won space to present their perspectives. But organizations of Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples, who bore the bitter brunt of the conflict and lived in areas in which guerrillas will be demobilized, have not been invited to share their collective views. They must be heard before the accords are finalized.

The Colombian government and the remaining major guerrilla group, the ELN, now in preliminary talks, must also launch negotiations -- or the conflict will not truly end. Is the accord perfect? Far from it, as no peace agreement is perfect. It does sacrifice some justice for peace. The transitional justice agreement provides alternative penalties for those who confess their crimes; guerrillas who committed grave abuses will not get the jail time they deserve. While those who do not confess will face jail.

Human rights groups also remain greatly concerned that soldiers who committed extrajudicial executions and other crimes against humanity and high-level officials who command responsibility in such crimes could be let off the hook. How the accord will affect these cases is murky. These cases must go forward in the civilian justice system.

The Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas should listen to voices of victims as they finalize negotiations. Colombian civil society and the international community will then need to press hard for the maximum possible truth, justice, and reparations once peace is declared. After an accord is signed, Colombians must construct peace from the ground up, day by day, village by village, farm by farm, city by city. Colombians, especially in rural areas, will continue to face threats from mobilized guerrillas; "bacrim" or paramilitary groups, the rightwing insurgents that never fully demobilized; and those local politicians, companies and military members still linked to paramilitary groups and opposed to victims reclaiming their land and rights. Human rights defenders could face escalated violence, and communities in former conflict zones will confront risks of sexual violence. Indeed, Colombian activists warn that we should talk about the "post-accord," not the post-conflict, period.

The United States and the international community can help by funding and supporting Colombian civil society initiatives to construct peace and verify the accords and Colombian government efforts to strengthen civilian institutions in war-torn areas. The international community must challenge Colombia to address the vast inequality that fueled the conflict.

As President Santos visits Washington, it's uplifting to see the White House supporting peace. But the White House is also celebrating "the success of Plan Colombia," the $10 billion in U.S. support for Colombia since 2000.

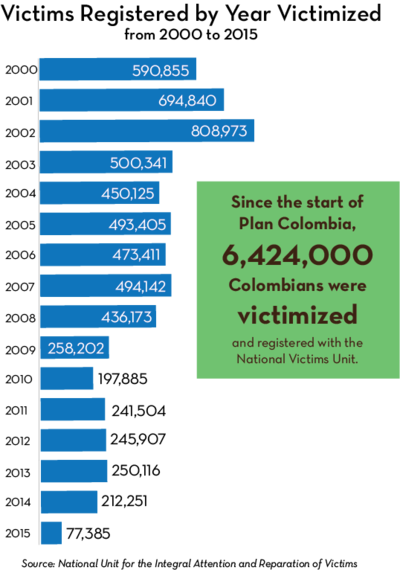

For those who have borne the brunt of the conflict, such words hurt. During the time period of Plan Colombia, with the U.S.-funded escalation of war, 4 million people were displaced. Paramilitaries committed massacres of men, women and children, abetted all too often by members of the army. More than 6 million people became victims of the war.

See the Latin America Working Group (LAWG)'s infographics on the Human Costs of the Colombian Conflict and the Human Rights Costs during Plan Colombia, as well as an interactive webpage from our partner organization the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) for a deeper look into the impacts of Plan Colombia.

At the height of Plan Colombia and of U.S. military aid and training, members of the Colombian armed forces are alleged to have murdered more than 4,300 civilians--mainly to up their body count. Most were young men from poor neighborhoods, men whom the soldiers thought would not be missed. They were often recruited with promises of jobs, then murdered and dressed in guerrilla uniforms.

During Plan Colombia, U.S.-funded intelligence services spied on and threatened journalists, human rights defenders, church leaders, opposition politicians and Supreme Court magistrates.During Plan Colombia, more than 1,000 trade unionists were murdered. Human rights defenders were killed, threatened and disappeared. Let's stop being blind to that terrible history. And let's not repeat it anywhere else, ever again.

But there's hope looking forward. After 220,000 dead (80 percent of whom were civilians), tens of thousands disappeared, countless victims of sexual violence, and more than 6 million internally displaced, it's time to stop the war. The international community, and especially the United States that backed this cruel war, should support this historic chance for peace.