I am a neuroscientist, doing research and living in The Bronx. I study the brain systems of love and relationships, which are curiously related to brain systems of hunger and thirst. Valentine's Day is special for me.

I live in a small town area in the Bronx called City Island. City Island resembles an old New England shipbuilding village, has many fish restaurants, boats and a nice place for exercise and personal training. As I walk through my neighborhood these days to get to the exercise place, I am charmed by exuberant shiny red hearts streaming down a front-steps railing. At another house a large Valentine heart hangs over a Christmas wreath, as if to seamlessly spread joy and gifts from one holiday to another. A flower basket of shiny red hearts hangs on another door as a reminder that the month of May and flowers will come. Romantic love knows no season, but it's great to celebrate it in the middle of winter when some of us crave a little warmth, temperature-wise and relationship-wise.

What is love? How about a simpler question -- Is romantic love an emotion? I bet you would say it is. I thought so before I started my research, but now I have a different answer for the question. But also, I constantly ask, how can research on the brain physiology of love be relevant to my neighbors on City Island behind the doors with hearts, and the doors without?

I love my work. There is no greater fascination for me than how the brain organizes behavior. Physiology of mind. What a concept! Even the cells of the brain have a raw beauty and instant fascination for me. It may be their complexity and likeness to trees, stars and planets. Scientists label brain cells to study them with shiny fluorescent colors of green and blue -- even red. When I look through the microscope at the brain, I see a universe in each square millimeter of tissue. For me, it is this brain-universe that underlies behavior, even romantic behavior and feelings. When I first began human brain mapping studies of romantic love (with Art Aron and Helen Fisher, Deb Mashek and Greg Strong), I was excited that I was going to see the brain systems of natural euphoria, an emotion. Others had studied drug-induced euphoria. Natural euphoria had seemed too ephemeral for a scientist to study. This would be a great adventure.

Luckily we were all brave enough to attempt the study of early-stage, intense romantic love. I must say, Helen Fisher, an anthropologist, was a driving force. She put together the words that made the study of love a rational choice. In brief, we were built to experience romantic love; nature designed it into our behavioral repertoire, and it may be an integral part of the human reproductive strategy. Art Aron, a social psychologist, set up the difference between emotion and motivation, and introduced me to the Passionate Love Scale (devised by Elaine Hatfield in 1986). I had the neuroscience and neuroanatomy background necessary to interpret the brain scans. If a dopamine-rich reward system were involved in romantic love, I would see it. After well over 10 years of research, my short answer to the question, "Is romantic love an emotion?" is "No, it is a motivation." Emotions vary around romantic love: you can feel euphoria, anxiety, surprise, even anger, but there is a core feeling that doesn't change and it influences our every move and thought when we are in love: it is motivation. The other person becomes a goal in life.

You are motivated when you are thirsty or hungry. Remember how good water tastes after a workout? (Or cold milk after a thick peanut butter and jelly sandwich?) Finding water (or milk) becomes a goal. We take the good taste of water for granted, like we take standing up against gravity on a treadmill for granted. But you need a reward system in your brain to tell you that the water is good. That system isn't so far from the reflex system that keeps you standing. Think about it some more -- you need that water (or milk), especially if you have to wait for it. Need is a special word here. The specially activated brain system common to everyone in love who we studied was a reward system that signals reward and need. It is in all mammals. It's at an unconscious level, like standing up. We don't have to think about it. It is taken care of for us at a primitive level. Nature saw it as that important.

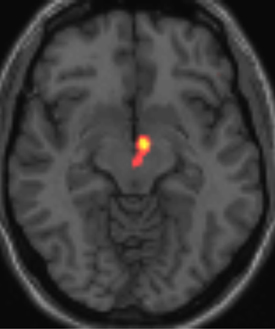

Brain scan data of the reward system activation in a group of people who were in the early stage of romantic love

What is this thing called love? I now see it as part of a built-in survival system. It is like thirst and hunger. (Songwriters, playwrights and novelists agree!) It leads us to pair up. If you are in the early stages of romantic love, you travel from NY to San Francisco (or farther) for love. Very often, love lasts more than a year, unlike euphoria. You arrange your life to be with your beloved. You may even get married or live with the person, for proximity -- it's nice to cuddle up on a cold February evening. Everything about your life changes when you experience romantic love. If you are the king of England, you might step down from your throne for love. One did.

Some people get married, buy a house, and put shiny red hearts down their front steps. They see those hearts when they come home, and I think it makes them feel good. It makes me feel good, too. I think it reminds them of those heady, early days, of romantic love. Couples therapists tell us that is a good thing to do, to remember what drew you to your partner early on, to remember the good times. Brain mapping research can help us all to understand ourselves better, help us to understand why it can be important for some of us to form pairs, and to reinforce therapeutic thoughts and behaviors in our everyday lives.

My personal trainer at the exercise place on City Island is a great guy. I know he has a serious girlfriend. I am concerned for him, because I think he is about to become a TV star and he needs a girl who will stick with him through tough times of sudden stardom, if it happens. He said to me last week, "Oh, I know I have her support no matter what. For her, if I'm wrong -- I'm right!" My eyes widened. He had just perfectly summarized the discussion for of a new set of results I'm writing with Mona Xu and Art Aron to try to predict relationship longevity from brain scans done during early-stage romantic love! His girlfriend is showing a super-positive attitude, and that may be important for a long relationship. A hugely positive motivation toward our partner is great for Valentine's Day, certainly. More on that experiment another time. In the meantime, I know some people are smiling when they see a red heart this week, and it is their reward system that makes it possible. For those not in love, have patience with those who are -- they are ensuring their mutual protection, and that the human race survives.

To read one of the first brain scanning papers about early-stage, intense romantic love, go here.