The aviator glasses are a bit rounder. So is the man.

But the dry humor that helped ex-marine Terry Anderson overcome near seven years of Hezbollah captivity testifies to stamina and resolve in returning to Lebanon with American journalism students to teach them that not all Lebanese, Arabs and Muslims are terrorists.

"We have to make sure the labels we use are accurate," insisted the former regional correspondent for The Associated Press, noting that U.S. media were generally very sloppy. "You cannot see mention of Islam in the United States without a connection with terrorism or fundamentalists."

Terry Anderson (Abu-Fadil)

He said there were over a billion Muslims in the world -- most of who were not Arabs - and more Muslims in the United States than Presbyterians, who looked just like everybody else.

"It would be nice if we could be more careful, more accurate in our simplifications," he said.

Anderson said U.S. media had not done a good job of reporting conflicts in which America had been involved and told Lebanese intellectuals at a gathering that Arabs had much better news sources available to them than most Americans.

A key reason for his program, and one for which he made a documentary about Lebanon, was his disgust with the prevailing view of Islam and Lebanon in the United States after his release.

"In 1983, when I took over the Beirut office, I banned the word terrorist from AP copy. I thought it was politically loaded and dangerous," he said.

But some people still use the term, he admitted, asking whether one could explain the difference between a man who straps a bomb to his waist and blows himself up in a public place and a man who puts on an olive drab uniform, finishes his cup of tea, climbs into his F-16 and bombs a (Palestinian) refugee camp, or a small village in Afghanistan.

"I teach classes in Middle East affairs," said Anderson who criticized the Bush administration for encouraging stereotypes and misunderstandings by fomenting xenophobia of Muslims and the Middle East.

He lauded President Barack Obama for understanding the need to reach out to the Arab and Islamic worlds by feeling with them, instead of demonizing them.

"And that's encouraging," said Anderson who also instructs his charges in fully packed classes at the University of Kentucky on good journalistic practice and was in Beirut this week to prepare for next summer's five-week trip with his students that involves meetings with journalists, politicians and scholars.

The assignment includes a journalistic project to be posted on a website and made available for publication. A three-year commitment by Lebanese philanthropist Issam Fares to fund the project allows Anderson to bring up to six students during summer breaks.

"The point of the program is to allow future foreign correspondents to understand how people in the Middle East look at Middle East affairs - a point of view that, unfortunately, they do not get in the United States," said Anderson. "And I think it's important."

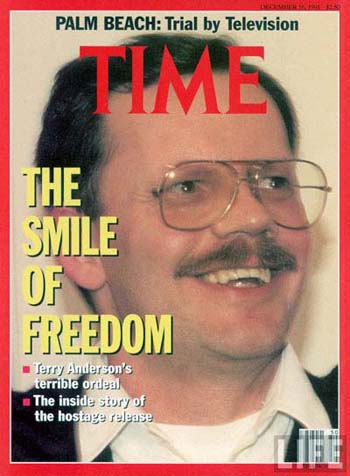

Time magazine cover of Anderson's release in 1991

It's a brighter picture than that of Anderson as the longest held Western hostage during Lebanon's 15-year civil war.

It was amusing hearing him complain to a waiter at a trendy Beirut restaurant with an avant-garde French name that he preferred Arabic coffee to espresso.

Walking around the Hamra district he could not find a single place that served Lebanese coffee, he lamented. It was all espresso.

People have asked him since his release in 1991 if he'd go back to cover Lebanon, and he said he would probably make the same decision, but wouldn't want to be kidnapped for seven years again.

"I wish I had not gone to play tennis that particular morning," he said of the day he was nabbed on a West Beirut street in 1985.

He did not regret coming to Lebanon, where he developed a considerable affection for the country and its people, and even acquired a Lebanese wife at the time.

In 1995 he published a bestseller memoir of his captivity, Den of Lions (http://www.amazon.com/Den-Lions-Terry-Anderson/dp/0345390547).

Den of Lions memoir of captivity

(Random House)

Asked about the hazards correspondents faced and whether fear played any role in reporting, Anderson replied: "Absolutely. If it doesn't, you're a fool. "

Anyone who goes into a dangerous situation and is not scared was not somebody he wanted to be with, since they would probably get him killed.

But Anderson acknowledged that fear was good for journalists as it made them cautious.

"Unfortunately, I wasn't scared enough, and I wasn't cautious," he admitted. "I got caught because I refused to take the precautions that I probably should have."

And, he strongly believes his abduction was political -- never about religion.

Who were the abductors? The Shiite militia Hezbollah (Party of God), specifically, Imad Mughnieh, he insisted.

"Hassan Nasrallah denied it of course when I interviewed him in 1995. But there's no doubt about it. Mughnieh, of course, has gone on to his just reward" (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/magda-abufadil/how-to-cover-a-hijacking_b_87411.html).

How did he know Mughnieh was in charge of foreigners' kidnappings?

"I'm a journalist. I did a year-and-a-half of research afterward and gathered an awful lot of information. It was not very difficult. I actually have the names of nine members of Islamic Jihad," he said.

Anderson agrees he was luckier than thousands of kidnapped Lebanese who never made it, because he was foreign.

When he asked Hezbollah leader Nasrallah about the kidnapping and whether it was wrong, the cleric replied it was just something that happened during the war.

"I didn't really disagree with him," Anderson said, adding that it nonetheless took away many years of his life, and that kidnapping for political purposes was wrong.

It was especially difficult to understand how people who prayed five times a day to "Al Rahman Al Rahim"(God the Merciful, the Benevolent) could kidnap others.

"But it has nothing to do with Islam either. Islam is not the only religion to be used to justify bad acts," he said. "If you've ever listened to the Rev. Ian Paisley in Northern Ireland, you'd know what I'm talking about."

So what does it mean to be a journalist in the 21st century, given the tremendous changes from traditional practices? To Anderson, the tools, or medium used, have nothing to do with whether or not one is a journalist.

"I don't think blogs Twitter, Facebook or any of that stuff is going to replace journalism," said the traditionalist who loves the Web and is on Facebook. "Journalism can only be (practiced) by professionally trained, dedicated, ideologically committed people."

Anderson, an Iowa State University alumnus with a degree in broadcast journalism, also taught at Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism and the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University before moving to the University of Kentucky.

He's been involved in press freedom issues with the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (www.cpj.org) and ran as a Democrat -- but failed -- to land an Ohio congressional seat. His opponent accused him of dealing with terrorists.