What does it take to sustain a single character for 74 years?

Since Batman's first appearance in May 1939, hundreds of writers, artists and editors have applied their craft and their personalities to the Dark Knight, reinventing and rebranding him from decade to decade (in the 50s, Batman traveled to the moon to fight aliens; in the 60s, he walked down the street in broad daylight and signed autographs).

"Creating the Bat" takes just a short peek into this never-ending process, asking five -- or, in this particular case, two -- quick questions to the creators who have helped to make the Batman what he is today.

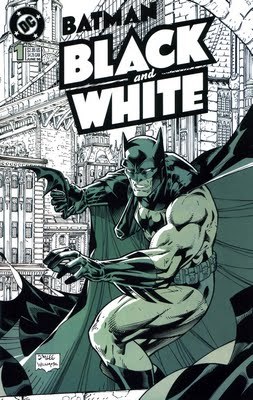

Scott Peterson joined DC Comics as the assistant to Batman Group Editor Denny O'Neil in 1991. Peterson quickly established himself as a capable and knowledgeable overseer -- one associate once described him as one of the greatest storytellers in the comics medium he had ever worked with -- and was rewarded by being promoted to an editor in his own right in 1993, being given the reigns of Detective Comics. By the time he retired from his editorial role at the company, he had also helmed Nightwing, Batman: Black and White (an acclaimed anthology miniseries, which he was nominated an Eisner award for), and The Batman Adventures (based off of the animated Batman television series).

In 1998, Peterson went freelance, working on comic books (such as, Batman: Gotham Adventures, a young-readers title, and the first ongoing Batgirl series), children's books (including various Disney and, of course, Batman titles) and even videogames (Batman: Dark Tomorrow for Microsoft Xbox and Nintendo GameCube, and Superman: The Man of Steel for Xbox). His current projects include music reviews at Reason to Believe and his Uncivil War ebook series.

Missed part one of this interview? Learn more at here.

What do you think has distinguished your run on Detective, both before and since?

Well, I inherited the title and the creative team from Denny O'Neil, so more than anything, I thought of myself as caretaker on the flagship title of DC Comics -- a position I took extremely seriously, and I'm incredibly proud to have been the editor on both Detective Comics 700 and Detective Comics 726, which was the 700th issue since the character had debuted in Detective Comics 27, way back in 1939.

But, overall, I'd have to say it was really a continuation of what Denny had started, and I'm very happy with that. Every issue was, I believe, written by the redoubtable Chuck Dixon, and almost all of them were penciled by the great Graham Nolan, and much of the run was inked by Scott Hanna, and I think the legendary John Costanza might have lettered every issue, so there was a considerable amount of creative continuity. Later, we started bringing in different inkers for different story lines, and we switched colorists and often had guest cover artists, so there was also enough change to keep things fresh. I think our issues were outstanding Batman stories told extremely well with, for the most part, a detective bent to them (appropriately and intentionally) and very high production values.

As for the title since, I'm afraid I'm not sure I've read an issue since I left. At the risk of sounding like a complete prat, when I work on a book, I put an awful lot of my soul into it, so once I'm gone, I'm gone. After all, if the book goes downhill, it'll break my heart. And if gets even better, well, that's pretty painful too.

So, I saw Detective as being one of the bedrocks of the Bat books and the DC Universe in general, which is why I used other books as a chance to experiment more. If you couldn't really change the essential Batman character -- and I didn't want to -- you had more leeway in other comics in the same orbit, such as Nightwing, or Catwoman, or Robin. When I started The Batman Adventures, the first comic to tie in with the amazing Batman: The Animated Series television show, I decided to play with the actual format a bit by making each issue self-contained -- which is obviously an old concept (the original, in fact), but which was very much going against the grain in the early 1990s. After a few issues -- and this was one of the few times I did get kinda tyrannical -- I decreed that every issue had to start on a splash (again, what's new was once old) and no page could have more than four panels on it, and even fewer, if possible. I wanted to try to imitate the speed of animation by giving fewer panels per pages, making it a breezier read. That would also make each panel bigger, which would be more accessible to the youngest readers. The goal was to make the comic something like a superhero version of a Chuck Jones cartoon -- a hoot for the youngest readers, but with hidden complexities and depths, so that the most sophisticated readers would get even more out of it. Thanks to the phenomenal creative team of Kelley Puckett, Mike Parobeck and Rick Burchett (with Ty Templeton kicking things off perfectly), I think we succeeded. What was really flattering was how very quickly our title -- The Batman Adventures -- become a sub-genre unto itself, with other publishers naming their own animated tie-ins: X-Men Adventures, Spider-Man Adventures, WildC.A.T.s Adventures and so on and so forth.

Are there too many Bat books?

The market doesn't seem to think so. And the Bat books certainly seem to be able to attract top-flight talent still, so it doesn't appear that there are too many. I do worry that having so many titles devoted to any one character, whether it's Batman or Superman or Spider-Man or the X-Men or whomever, leads to a captive market, squeezing out opportunities for new books and new characters, whether from one of the big two, or smaller, independent publishers. It seems pretty obvious to me that's what we have now, but, then again, I think that's what we've had for 20 years, including during my tenure on the books. I don't think it's an ideal situation for the health of the industry, but Marvel and DC are publishers, and publishing's a business, so you can't exactly blame them for deciding to put out books that make money.

Previous installments: