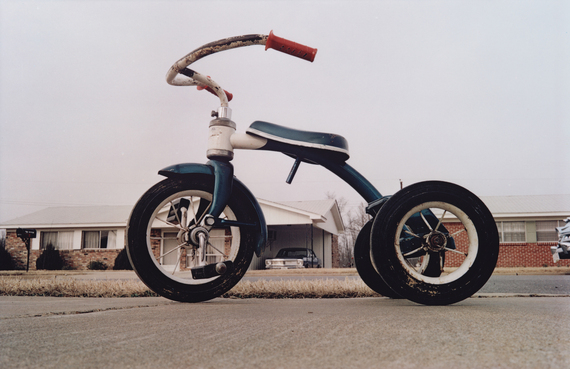

William Eggleston, Untitled (Memphis), 1970. © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

The argument could be made.

American photographer William Eggleston (1939-) is widely considered "the father of color photography"; the 1976 exhibition of his work at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, is considered the most important solo exhibition of color photography to date; and this image, entitled at times Tricycle, Memphis and Untitled, served as the cover image of MoMA's exhibition catalogue.

So what is going on in this picture?

Let's begin with the use of color, which was (and in many ways, still is) the most commonly-discussed attribute of Eggleston's images. There's good reason for this. At the time of Eggleston's exhibition, color was shunned in serious photography circles. Until then photographers used color only for advertising and journalism, and most influential voices in the field would echo Walker Evans' opinion, voiced in 1969, that color photography was "vulgar." Furthermore, even though we retrospectively understand Eggleston's MoMA exhibition to be hugely influential, it was widely despised by the mainstream art world of the time, primarily because of its powerful assertion that color photography should be considered an art form.

Color wasn't just an important attribute for Eggleston but arguably the most important. He famously said that what he chose to take pictures of were just pretexts for the making of color photographs. Eggleston's 1974 adoption of dye-transfer printing (which was the only manual process that allowed photographers to manipulate color before digital photography) was a major turning point for him, and one can understand how liberating and exciting this new technology must have been for him to work with. Certain works by Eggleston seem wholly obsessed with color, such as his 1973 photograph, Greenwood, Mississippi (which is almost entirely concerned with the blood-red color of a ceiling). Tricycle is less intensely-focused on color. Yet at the same time, there are subtle gradations of tans and browns, a sharp contrast created between the blues and whites of the bike, and then there is the sharp red of the handlebar grips.

Let's move on to discuss what is photographed here: banal, everyday, common objects and imagery. This has been a common trait of Eggleston's work throughout his career. On one hand this focus shares many similarities to the work of Eggleston's influences, such as Walker Evans, and Robert Frank or others grouped into what is referred to as New Documentary Photography or New American Color Photography, i.e. Diane Arbus, Gary Winogrand, Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, Joel Sternfeld, Richard Misrach and William Christenberry. Outside of photography, this also connects Eggleston to Pop Art. At the same time, unique to Eggleston is his de-emphasis of the people involved and the fact that upon closer inspection, his images reveal something slightly off, in a way which was much more subtle than in, for example, Diane Arbus's work. For this reason, photographer Lewis Baltz once called Eggleston's work, "images of the American home place, inviting on their surface and ice cold at their heart." In Eggleston's world, objects often fray at the edges, erode or allude to the underside of society. Take Tricycle, in which a familiar American scene of a tricycle on a sidewalk upon closer examination yields up the rusty handlebars, worn tires, rims and spokes of the tricycle, as well as dead grass, empty yards, leafless trees and a cold white-gray sky.

The particulars of Tricycle's composition and framing were also important ways Eggleston used to defamiliarize common imagery. The tricycle is monumental--Eggleston laid down on the ground to take this image and we look up at it looming over the houses and everything else in the picture. Eggleston suggested his interest in this point-of-view was inspired by his desire to create a child's point-of-view or even an insect's. He has also talked about making pictures that looked as if they weren't taken by a human being. Then there is the framing of the shot. A car peeks in at the right side, both houses are not shown completely but are either blocked or cut off. Also the lines of the sidewalk, the house and the road are slightly off-parallel creating a consistent sense that the image is not in line, and off-kilter.

What's the story of this picture?

On one hand, it's impossible to know exactly, since Eggleston rarely discusses the details behind any of his pictures. On the other hand, like so many of his images, the ambiguity and subtle allusions created by his choice of subject matter, lack of figures and composition allow for many possible readings. Critics often see these as dark narratives, comparable to the movies of Alfred Hitchcock or David Lynch. For example, the empty tricycle, or the front of a car just peeking into the right side of the frame might be--according to familiar Hollywood narratives--the visit of a long-lost father, the scene of the death of a child (whose parents refuse to move his toys) or the front yard of a dysfunctional family that does not tend its yard (as opposed to the order of the rest of the suburban landscape). A more light-hearted reading could allude to the various ways kids play. Children might have no interest in riding a tricycle, and would find it more fun to lie down and look up at it, imagining it as a motorcycle. Or they might just want to lie on the ground and look up at the sky and space out. There is also something subtly phallic about the adjustment pole of the seat. Maybe Tricycle is a rumination on the masculine trajectory of mid-century America? Young boys start out riding tricycles (which are highly suggestive of hot rod motorcycles) and are thus fed the dream early on about the power of the road and owning a car; for this reason the sedan in the background may have been framed by the bike. Another reading that has been proposed is biographical: A recent documentary about the artist shows a family snapshot with Eggleston as a child with a tricycle in the background. Maybe this is the artist reflecting on his own childhood.

As always, please feel free to send me your feedback, either here or on Twitter. This is the eighth in a series of posts on individual artworks. Previous posts have concerned one of Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills, Jean-Michel Basquiat's Pegasus, 1987, Keith Haring's "Crack is Wack" mural, Banksy, and Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.