The past 20 years have quietly hosted a series of financial revolutions and a radical redistribution of wealth, income and opportunity. While we all know that things have changed, few really factor just how different the new America really is. To the extent that we confront these changes at all, it generally comes in the form of leading voices cherry picking the most positive new developments and heaping on exaggerated praise. There is plenty to be glad of. There is much to lament. The housing downturn may foster re-assessment. The debt debacle could be a catalyst for change and realization of past changes. There is no longer significant doubt that housing will continue down and drag the economy with it.1 Housing quakes are produced by larger tectonic shift. This blog attempts a whirlwind tour.

A financial revolution shaped the boom and will shape -- and be reshaped by -- the bust. This is what has been driving housing markets, house finance firms, lenders and global stock markets. In case you were not aware, we are in the midst of a serious market correction -- globally. Since 2004, we had been in a global stock market boom. The recent run-up, and run off a cliff, share common roots. The plates under our economic ground have been heaving and shifting. Some economic areas have been thrust upward, others have been pulled down. Seismic activity is everywhere.

Shifting Plates

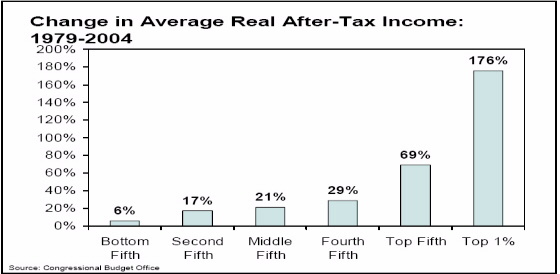

Real wages began a long stagnation in the mid 1970s. Americans have struggled to keep wages and salaries growing at the rate of price increase. Lost in the averages are vastly divergent fortunes. The top quintile, 20% of earners, has done pretty well. The top 5% and 1% of earners have done even better. Pain is clustered -- regressively distributed -- across the bottom 60% of earners. The graph below -- from The Congressional Budget Office and The CBPP -- displays drastic change.2

Wealth is more unequally distributed than income. This has been the case throughout history but, the trend has grown significantly since the 1980s. America is not unique in this regard. A recent study by the United Nations University, UNU-WIDER, reveals that the richest 1% of global households own 40% of assets and the richest 10% own 85% of global assets.3 The UN study reveals that the wealthiest 10% of Americans account for about 70% of asset wealth. Inequality of wealth has been growing fast in the US and globally.

Inequalities of wealth and income create vast pools of liquid assets searching for investment returns. The present distributions of wealth and income also create needs and desires for goods, services and opportunities from all those who lack the capital to purchase, invest, speculate and consume. Financial firms, innovations, contracts and markets arise and develop to facilitate gains for creditors and loans for debtors. Rising inequalities of wealth and income increase the supply of funds and the demand for them. Risks and difficulties of collection threaten. Revolutions in communications, information technology and risk modeling have occurred. The dominant economic trend has been toward freer trade and markets. Risks and opportunities have grown as economic borders and government restrictions fall. The landscape has shifted. Dislocation and change are rapid. Some call it globalization -- that is a different blog for another day.

The Financial Revolution

What made this possible? Origination to distribute credit and global deregulated savings markets answered our consumption prayers from 1998-2007. The US has not been saving, and earnings are stagnant. Where did all the money we borrowed come from? Financial engineering and foreign credit saved the day. After the Asian Financial Crisis (1997-8) there was a rapid completion of global financial deregulation. Controls on inflows and outflows of wealth and international banking were relaxed almost everywhere.4 International financial institutions and flows have grown astronomically, trebling in the ten years 1996-2006. Huge pools of Asian savings were opened up and deployed, financial institutions became global and the US moved toward its present rate of net importing $2.5 billion per day in foreign capital. This is how America became the greatest debtor nation in world history. We presently owe the rest of the world $2.6 trillion more than they owe us.

Borrowing on new, nimble, integrated, global, financial markets was not enough. Enter structured debt product and innovation. Financial firms faced great risks and fantasized massive rewards. The world was awash in liquid wealth -- all that upward wealth distribution. At about the same time, China, India and Eastern Europe joined the game. There were endless demands for credit from firms struggling to adjust to changing business climates and people trying to stay or become middle class consumers. It was just so risky, unless innovation could allow the slicing, dicing and re-pricing of risk? It can -- to a limited extent. The capabilities of slicing, dicing and re-pricing gave us our boom. The limitations of these innovations have become the earthquake rattling markets and financial institutions.

Deregulation and all that investment cash found its way into the peripheral areas of finance- as well as the core regulated and insured banking institutions and brokerages. New products became popular in the 1980s alongside the great equity boom (1982-2000). One of these new products has the mortgage backed security (MBS). The idea -- that was to change debt -- was to buy loans from an originator or granter of credit. Once bought the loans were to be packaged. The loans would become less risky through bundling many together and reducing the risk from any single default. Money could go quickly back to the originator to lend more. Investors would have a nice safe product. Products made in this process are called asset backed securities.

Once the new financial mass production lines started rolling, it became clear that asset backed securities could be sliced and diced into all kinds of specialized vehicles, structured products. New types of asset backed securities were invented, sold and traded at an astonishing pace. This allowed firms to collect fees to create and trade new products. Credit was extended far and wide. Debt became the raw material of a bonanza. More and more people were extended credit on easier terms. Financial firms made great money. The public got credit. Investors borrowed lots of money to increase returns. Huge sums of money were borrowed to speculate on assets backed by pools of interest payments on money other people had already borrowed.

Innovation raged. New products and markets were created at dizzying speed with light, partial or, no regulation. Ratings agencies like Moodys, Standard and Poors and Fitch worked with producers to create models of the risk and value of exotic new assets. Hedge funds, banks, insurers, pension funds and others used cheap borrowed money to increase returns. For a while the good times rolled. Nowhere more so than in housing markets. Mortgages were written and sold to make structured products, collateralized mortgage obligations. This made credit easy, houses seem affordable and prices soared. Very similar things happened with car loans, credit card loans, corporate borrowing and many kinds of debt. Risks were sliced, diced, determined by the best and brightest using the best modeling techniques and sold. Special contracts were produced and sold that offered further risk protection to those who felt they needed it. Credit derivative contracts and credit default swaps came into being and were themselves made into structured products.

The light regulation and global integration meant that we could borrow from the world. They could lend and they could and did buy our loans in complex processed forms. Like processed food, it is hard to tell what is in processed loans-structured products. There can be great complexity and many ingredients. Great big, hard to understand production lines feed into the final product. If there are bad ingredients or dirty processes, it is hard to tell where and when the contamination got in. When trouble is finally detected and admitted, there is contagion, panic and generalized fear. Authorities tell reassuring fibs until they are forced to promise better over-sight next time. Some producers and sellers can be made into scape-goats. Demand dries up for the tainted product and some consumers never return. Sound familiar?

The present housing downturn is being driven by the end of easy credit. For the last six years credit markets have been awash in funds. A secondary market for packaged and processed debt ballooned. It was a great time to lend and to borrow. Credit from appreciating house prices papered over growing inequality of wealth, income and opportunity. Middle and lower income Americans judge their well being by the quantity -- and quality -- of consumption goods. Times have been good by this measure. New SUVs, bigger and renovated homes, flat panel TVs, restaurant meals, kids in college have been abundant. Earnings have gone nowhere, vacations are down and hours are long. Debt to be paid threatens destruction to debtors and creditors. Luckily such trivial concerns rarely get mentioned and never long occupy our focus. Until they became the focus out of necessity.

While everyone was busy adjusting and trying to take advantage of the new landscape, the country changed. American consumers and government sold future income to creditors, foreign and domestic. Income and wealth were increasingly re-distributed upward. Democratic and middle class foundations were stressed and bent by the seismic activity. America became a mediocre place to try to better oneself. I know, everyone thinks this is paradise for the upwardly mobile. They have been increasingly, embarrassingly statistically incorrect for years. The US offers the second lowest opportunity for upward mobility in the developed world -- second only to the UK. Of course, there are greater chances in the US than most nations in our troubled world. Sadly and importantly, there is far less upward mobility in America today than in a long while. We have responded by disengaging from civic life and borrowing. Debt is no longer an option. Disengagement was a disaster. It is time to move forward armed with a realistic assessment of the recent past.